Man may deceive himself, may think that his knowledge grows and increases, that he knows and understands more than he knew and understood before; but sometimes he may be sincere with himself and see that, in relation to the fundamental problems of existence, he is as helpless as a savage or a little child and although he has invented many clever machines and instruments which have complicated his life, they have not rendered it any more comprehensible.

Speaking still more sincerely with himself, man may recognise that all his scientific and philosophical systems and theories are similar to these machines and implements, for they serve only to complicate the problems without explaining anything.

Among the insoluble problems with which man is surrounded, two occupy a special position — the problem of the invisible world and the problem of death.

Such an assertion, that is, that the division of the world into the visible and the invisible has existed always and everywhere, may appear strange at first; but in reality all existing general schemes of the world, from the most primitive to the most subtle and elaborate, divide the world into the visible and the invisible and can never free themselves from this division. No matter how he names or defines this division, it is always the foundation of man's thinking about the world.

The fact of such a division becomes evident if we try to enumerate the various systems of thinking of the world. First of all, let us divide all these systems into three categories:

In philosophy there is the world of events and the world of causes, the world of things and the world of ideas, the world of phenomena and the world of noumena. In Indian philosophy, especially in certain schools of it, the visible or phenomenal world — that is, Maya or illusion, meaning a wrong conception of the invisible world — does not exist at all.

In science, the invisible world is the world of small quantities and, strange though it seems, the world of large quantities. The visibility of the world is determined by the scale. The invisible world is on the one hand the world of micro-organisms, cells, the microscopic and ultramicroscopic world; still further it is the world of molecules, atoms, electrons, "vibrations" — and, on the other hand, the world of invisible stars, other solar systems, unknown cosmoses. The microscope expands the limits of our vision in one direction, the telescope in the other. But both increase visibility very little in comparison with what remains invisible. Physics and chemistry show us the possibility of investigating phenomena in such small quantities or in such distant worlds as will never be visible to us. But this only strengthens the fundamental idea of the existence of an enormous invisible world around the small visible world.

Mathematics goes even further. It calculates such relations of magnitudes and such relations between these relations as have nothing similar in the visible world surrounding us, and we are forced to admit that the invisible world differs from the visible not only in size, but in some other properties which we can neither define nor understand. This shows us only that laws inferred by us for the visible world cannot refer to the invisible world.

In this way invisible worlds — the religious, the philosophical, and the scientific — are, after all, more closely related to one another than they would at first appear. These invisible worlds of different categories possess identical properties common to all. These properties are:

This shows that on all levels of his development, man has always understood that causes of visible and observable phenomena lie beyond the sphere of his observation. He has found that among observable phenomena, certain facts could be regarded as causes of other facts; but these deductions were insufficient for the explanation of everything that occurred in himself and around him. Therefore in order to be able to explain the causes, it was necessary for him to have an invisible world consisting of "spirits" or "ideas" or "vibrations".

Man could never reconcile himself to the idea of death as disappearance. Too many things contradicted it. There were in himself too many traces of the dead: their faces, words, gestures, opinions, promises, threats, the feelings which they aroused, fear, jealousy, desire. All these continued to live in him, and the fact of their death was more and more forgotten. A man saw his dead friend or enemy in his dreams. He appeared exactly as he was before. Evidently he was living somewhere, and could come from somewhere by night.

So it was very difficult to believe in death and man always needed theories for the explanation of the existence after death.

On the other hand, echoes of esoteric teachings on life and death sometimes reached man. He could hear that the visible, earthly, observable life of man is only a small part of his life. And man, each in his own way, understood these fragments which reached him, changed them in his own fashion, adapted them to his own level of understanding, and built out of them some theory of future existence similar to existence on the Earth.

The greater part of religious teachings on the future life connect it with the idea of reward or punishment, sometimes in a disguised, sometimes in a veiled form. Heaven and hell, transmigration of souls, reincarnation, the wheel of lives — all these theories contain the idea of reward or punishment.

But religious theories often do not satisfy man and, in addition to the recognised orthodox ideas of life after death, there usually exist other, as it were illegitimate, ideas of the world beyond the grave or of the spirit world, which allow a greater freedom of imagination.

No religious teaching, no religious system, can by itself satisfy people. There is always some other, more ancient, system of popular belief underlying it or hiding behind it. Behind external Christianity, behind external Buddhism, there stand the remains of ancient pagan creeds (in Christianity the remains of pagan beliefs and customs, in Buddhism "the cult of the devil"), which sometimes make a deep mark on the external religion. In modern Protestant countries, for instance, where the remains of ancient paganism are already completely extinct, there have come into existence, under the outward mask of logical and moral Christianity, systems of primitive thinking of the world beyond the grave such as spiritualism and kindred teachings.

Theories of existence beyond the grave are always connected with theories of the invisible world; the former are always based upon the latter.

All this relates to religion and "pseudo-religion". There are no philosophical theories of existence beyond the grave. All theories of life after death can be called religious or, more correctly, pseudo-religious.

Moreover, it is difficult to take philosophy as a whole, so diverse and contradictory are the various speculative systems. Still, to a certain extent, it is possible to accept as a standard of philosophical thinking the view which can see the unreality of the phenomenal world and the unreality of man's existence in the world of things and events, the unreality of the separate existence of man and the incomprehensibility for us of the forms of real existence, although this view can be based on very different foundations, either materialistic or idealistic. In both cases the question of life and death acquires a new character and cannot be reduced to the naïve categories of ordinary thinking. For such a view there is no particular difference between life and death because, strictly speaking, for it there are no proofs of a separate existence, of separate lives.

There are not, and there cannot be, any scientific theories of existence after death because there are no facts in favour of the reality of such an existence, while science, successfully or unsuccessfully, wishes to deal with facts. In the fact of death the most important point for science is a certain change in the state of the organism which stops all vital functions, and the decomposition of the body following upon it. Science sees in man no psychic life independent of the vital functions, and all theories of life after death, from the scientific point of view, are pure fiction.

Modern attempts at "scientific" investigation of spiritualistic phenomena and similar things lead nowhere and can lead nowhere, for there is a mistake here in the very setting of the problem.

In spite of the difference between the various theories of the future life, they all have one common feature. They either picture the life beyond the grave as similar to the Earthly life or deny it altogether. They do not and cannot attempt to conceive life after death in new forms or new categories. This is precisely what makes all usual theories of life after death unsatisfactory. Philosophical and strictly scientific thought shows us the necessity of reconsidering the problem from completely new points of view. A few hints coming from the esoteric teaching partly known to us indicate the same.

It already becomes evident that if the problem of death and life after death can be approached in any way, it must be approached from quite a new angle. In the same way, the question of the invisible world must also be approached from a new angle. All we know, all we have thought till now, shows us the reality and the vital importance of these problems. Until he has answered in one way or another the questions of the invisible world and of life after death, man cannot think of anything else without creating a whole series of contradictions. Right or wrong, man must build for himself some kind of explanation, and he must base his treatment of the problem of death upon science or upon religion or upon philosophy.

But to a thinking man both the "scientific" denial of the possibility of life after death and the pseudo-religious admission of it (for we know nothing but pseudo-religion) and also different spiritualistic, theosophical, and similar theories quite justly appear equally naïve.

Nor can the abstract philosophical view satisfy man. Such a view is too remote from life, too remote from direct real sensations. One cannot live by it. In relation to the phenomena of life and their possible causes, unknown to us, philosophy is very like astronomy in relation to the distant stars. Astronomy calculates the movement of stars which are at colossal distances from us. But all celestial bodies are alike for it. They are nothing but moving dots.

Thus philosophy is too remote from concrete problems such as the problem of future life. Science does not know the world beyond the grave; pseudo-religion creates the other world in the image of the Earthly world.

Our basic conception of the world must be broadened. Already we feel and know that we can no longer trust the eyes with which we see, or the hands with which we touch. The real world eludes us in such attempts to ascertain its existence. A more subtle method and a more efficient means are needed.

The ideas of the "fourth dimension", ideas of "many-dimensional space", show us the way by which we may arrive at the broadening of our conception of the world.

The expression "fourth dimension" is often met with in conversational language and literature, but it is very seldom that anybody has a clear idea of what it really means. Generally the fourth dimension is used as the synonym for the mysterious, miraculous, "supernatural", incomprehensible, and incognisable, as a kind of general definition of the phenomena of the "super-physical" world.

"Spiritualists" and "occultists" of various schools often make use of this expression in their literature, assigning to the sphere of the fourth dimension all the phenomena of the "world beyond" or the "astral sphere". But they do not explain what it means, and from what they say one can understand only that the chief property they ascribe to the fourth dimension is "unknowableness".

Connecting the idea of the fourth dimension with existing theories of the invisible world or the world beyond is certainly quite fantastic for, as has already been said, all religious, spiritualistic, theosophical, and other theories of the invisible world make it exactly similar to the visible — and consequently "three-dimensional" — world.

Therefore mathematics quite justly objects to the established view of the fourth dimension as something belonging to the "beyond".

The very idea of the fourth dimension must have arisen in close connection with mathematics or, to put it better, in close connection with the idea of measuring the world. It must have arisen from the supposition that, besides the three known dimensions of space — length, breadth, and height — there might also exist a fourth dimension inaccessible to our perception

Logically, the supposition of the existence of the fourth dimension can be based on the observation of those things and events in the world surrounding us for which the measurement in length, breadth, and height is not sufficient, or which elude all measurement; because there are things and events the existence of which calls for no doubt, but which cannot be expressed in any terms of measurement. Such are, for instance, various effects of vital and psychic processes; such are all ideas, mental images, and memories; such are dreams. If we consider them as existing in a real objective sense, we can suppose that they have some other dimension besides those accessible for us, that is, some extension immeasurable for us.

The weak point of this definition is the proposition accepted as unquestionable that every mathematical formula, every equation, can have a dimensional expression. In reality such a proposition is entirely without ground, and this deprives the definition of all meaning.

In reasoning by analogy with the existing dimensions, it must be supposed that if the fourth dimension existed it would mean that side by side with us lies some other space which we do not know, do not see, and into which we are unable to pass. It would then be possible to draw a line from any point of our space into this "domain of the fourth dimension" in a direction unknown to us and impossible either to define or to comprehend. If we could visualise the direction of this line going out of our space then we should see the "domain of the fourth dimension".

Geometrically this proposition has the following meaning. We can conceive simultaneously three lines perpendicular and not parallel to one another. These three lines are used by us to measure the whole of our space, which is therefore called three-dimensional. If the "domain of the fourth dimension" lying outside our space exists, this means that besides the three perpendiculars known to us, determining the length, the breadth, and the height of solids, there must also exist a fourth perpendicular determining some new extension unknowable to us. Then the space measurable by these four perpendiculars could be called four-dimensional.

We are unable to geometrically define, or to conceive, this fourth perpendicular, and the fourth dimension still remains extremely enigmatic. The opinion is sometimes met with that mathematicians know something about the fourth dimension which is inaccessible to ordinary mortals. Sometimes it is said, and one can even find such assertions in literature, that Lobachevsky "discovered" the fourth dimension. During the last twenty years the "discovery" of the fourth dimension has been ascribed to Einstein or Minkovsky.

In reality mathematics can say very little about the fourth dimension. There is nothing in the hypothesis of the fourth dimension that would make it inadmissible from a mathematical point of view. This hypothesis does not contradict any of the accepted axioms and, because of this, does not meet with particular opposition on the part of mathematics. Mathematicians even admit the possibility of establishing the relationship that should exist between four-dimensional and three-dimensional space, i.e., certain properties of the fourth dimension. But they do all this in a very general and indefinite form. No exact definition of the fourth dimension exists in mathematics.

Lobachevsky actually treated the geometry of Euclid, i.e., geometry of three-dimensional space, as a particular case of a geometry which ought to be applicable to a space of any number of dimensions. But this is not mathematics in the strict sense of the word; it is only metaphysics on mathematical themes, and the deductions from it cannot be formulated mathematically or can be formulated only in specially constructed expressions which have no general meaning.

Other mathematicians regarded axioms accepted in the geometry of Euclid as artificial and incorrect, and attempted to disprove them on the strength, chiefly, of certain deductions from Lobachevsky's spherical geometry and to prove, for instance, that parallel lines meet. They contended that the accepted axioms are correct only for three-dimensional space and, on the basis of their arguments which disproved these axioms, they built up a new geometry of many dimensions.

But all this is not geometry of four dimensions.

The fourth dimension could be considered as geometrically proved only when the direction of the unknown line starting from any point of our space and going into the region of the fourth dimension could be determined, i.e., when a means is found of constructing a fourth perpendicular.

It is difficult to describe even approximately the significance which the discovery of the fourth perpendicular in our Universe would have for our knowledge. The conquest of the air; hearing and seeing at a distance; establishing connections with other planets or with other solar systems: all these are nothing in comparison with the discovery of a new dimension. But so far it has not been made. We must recognise that we are helpless before the riddle of the fourth dimension, and we must try to examine the problem within the limits accessible to us.

After a closer and more exact investigation of the problem itself, we come to the conclusion that it cannot be solved in existing conditions. The problem of the fourth dimension, though at first glance purely geometrical, cannot be solved by geometrical means. Our geometry of three dimensions is as insufficient for the investigation of the question of the fourth dimension as planimetry alone is insufficient for the investigation of questions of stereometry. We must find the fourth dimension, if it exists, in a purely experimental way, and also find a means for a projective representation of it in three-dimensional space. Only then shall we be able to create geometry of four dimensions.

The fourth dimension is unknowable. If it exists and if at the same time we cannot know it, that evidently means that something is lacking in our psychic apparatus, in our faculties of perception. In other words, phenomena of the region of the fourth dimension are not reflected in our organs of sense. We must examine why this should be so, what are our defects on which this non-receptivity depends, and must (even if only theoretically) find the conditions which would make the fourth dimension comprehensible and accessible to us. These are all questions relating to psychology or, possibly, to the theory of knowledge.

Further, we know that the region of the fourth dimension (again, if it exists) is not only unknowable for our psychic apparatus, but is inaccessible in a purely physical sense. This must depend not on our defects, but on the particular properties and conditions of the region of the fourth dimension itself. It is necessary to examine what these conditions are which make the region of the fourth dimension inaccessible to us, and to find the relation between the physical conditions of the region of the fourth dimension and the physical conditions of our world. Having established this, it is necessary to see whether in the world surrounding us there is anything similar to these conditions, that is, whether there are any relations analogous to relations between the region of three dimensions and the region of four dimensions.

Speaking in general, before attempting to build up a geometry of four dimensions it is necessary to create a physics of four dimensions, that is, to find and to define physical laws and conditions which may exist in the space of four dimensions.

Many people have worked at the problem of the fourth dimension. Fechner wrote a great deal about it. From his discussions about worlds of one, two, three, and four dimensions there follows a very interesting method of investigating the fourth dimension by means of building up analogies between worlds of different dimensions, i.e., between an imaginary world on a plane and the three-dimensional world, and between the three-dimensional world and the world of four dimensions. This method is used by nearly all those who have ever studied the problem of higher dimensions, and we shall have occasion to meet with it further on.

Professor Zöllner evolved the theory of the fourth dimension from observations of "mediumistic" phenomena, chiefly of phenomena of so-called "materialisation". But his observations have long been considered doubtful because of the established fact of the insufficiently strict arrangement of his experiments (Podmore and Hislop).

A very interesting summary of almost all that has ever been written about the fourth dimension up to the nineties of the last century is to be found in the books of C H Hinton. These books also contain many of Hinton's own ideas; but, unfortunately, side by side with the valuable ideas there is a great deal of unnecessary dialectic such as always accumulates around the question of the fourth dimension.

Hinton makes several attempts at a definition of the fourth dimension from the physical side, as well as from the psychological. Considerable space is occupied in his books by the description of a method, invented by him, of accustoming the mind to cognition of the fourth dimension. It consists of a long series of exercises for the perceiving and the visualising apparatus, with sets of differently coloured cubes which are to be memorised, first in one position, then in another, then in a third, and after that to be visualised in different combinations.

The fundamental idea which guided Hinton in the creation of this method of exercises is that the awakening of "higher consciousness" requires the "casting out of the self" in the visualisation and cognition of the world, i.e., accustoming oneself to know and conceive the world not from a personal point of view (as we generally know and conceive it) but as it is. For this it is necessary first of all to learn to visualise things not as they appear to us but as they are, even if only in a geometrical sense. From this there must develop the capacity to know them, i.e., to see them as they are, from other points of view besides the geometrical.

The first exercise suggested by Hinton consists in the study of a cube composed of 27 smaller cubes coloured differently and bearing definite names. After having thoroughly learned the cube made up of smaller cubes, it has to be turned over and learned and memorised in the reverse order. Then the relative positions of the smaller cubes have to be changed and memorised in the new order, and so on. As a result, according to Hinton, it is possible to cast out in the cube the concepts "up and down", "right and left", and so on, and to know it independently of the position with regard to one another of the smaller cubes composing it, i.e., probably to visualise it simultaneously in different combinations. This would be the first step towards eliminating the self-elements in the conception of the cube. Further on, there is described an elaborate system of exercises with series of differently coloured and differently named cubes out of which various figures are composed. All this has the same purpose — to cast out the self-elements in the percepts and in this way to develop higher consciousness.

According to Hinton's idea, casting out the self-elements in percepts is the first step towards the development of higher consciousness and towards the cognition of the fourth dimension. He says that if there exists the capacity of vision in the fourth dimension, that is, if we are able to see objects of our world as if from the fourth dimension, then we shall see them not as we see them in the ordinary way, but quite differently.

We usually see objects as above us or below us or on the same level with us, to the right or to the left, behind us or in front of us, and always from one side only — the one facing us — and in perspective. Our eye is an extremely imperfect instrument; it gives us an utterly incorrect picture of the world. What we call perspective is in reality a distortion of natural objects which is produced by a badly constructed optical instrument — the eye. We see all objects distorted, and we visualise them in the same way. But we visualise them in this way entirely owing to the habit of seeing them distorted because the habit created by our defective vision has weakened our capacity for visualisation.

Hinton asserts that there is no necessity to visualise objects of the external world in a distorted form. The power of visualisation is not limited by the power of vision. We see objects distorted, but we know them as they are. We can free ourselves from the habit of visualising objects as we see them, and we can learn to visualise them as we know they really are. Hinton's idea is precisely that before thinking of developing the capacity of seeing in the fourth dimension, we must learn to visualise objects as they would be seen from the fourth dimension, i.e., first of all, not in perspective but from all sides at once, as they are known to our "consciousness". It is just this power that should be developed by Hinton's exercises. Development of this power to visualise objects from all sides at once will be the elimination of the self-elements from mental images. According to Hinton, "casting out the self-elements in mental images must lead to casting out the self-elements in perceptions". In this way, development of the power of visualising objects from all sides will be the first step towards development of the power of seeing objects as they are in a geometrical sense, i.e., development of what Hinton calls a "higher consciousness".

In all this there is a great deal that is right, but also a great deal that is arbitrary and artificial. First of all, Hinton does not take into consideration the difference between the various psychic types of men. A method that may prove satisfactory for himself may produce no results, or even contrary results, for other people. Also, the very psychological foundation of his system of exercises is too unstable. Usually he does not know when to stop; he carries his analogies too far and thus devalues many of his conclusions.

Hinton approaches the question of the fourth dimension by observing that we know three kinds of geometrical figures:

Let us imagine a straight line limited by two points, and let us designate this line by the letter a. Let us imagine this line as moving in space in a direction perpendicular to itself and leaving a trace of its movement. When it has traversed a distance equal to its length, the trace left by it will have the form of a square, the sides of which are equal to the line a. The area of the square surface will be a2.

Let us imagine this square moving in space in a direction perpendicular to two of its adjoining sides and leaving a trace of its movement. When it has traversed a distance equal to the length of one of the sides of the square, its trace will have the form of a cube of volume a3.

Now if we imagine the movement in space of this cube, what form will the trace of its movement take? In other words, what meaning can we assign to a4?

Examining the correlations of figures of one, two, and three dimensions, i.e., lines, planes, and solids, we can deduce the rule that a figure of a higher dimension can be regarded as the trace of the movement of a lower dimension.

On the basis of this rule we may regard the figure a4 as the trace of the movement in space of a cube.

But what is this movement, the trace of which becomes a figure of four dimensions?

If we examine the way in which figures of higher dimensions are constructed by the movement of figures of lower dimensions, we shall discover in these formations several common properties and several common laws.

When we consider a square as the trace of the movement of a line, we know that all points of this line have moved in space; when we consider a cube as the trace of the movement of a square, we know that all the points of the square have moved. Moreover, the line moves in a direction perpendicular to itself; the square in a direction perpendicular to two of its dimensions.

Consequently, if we consider the figure a4 as the trace of the movement of a cube in space, we must remember that all the points of the given cube have moved in space. Moreover, we may deduce from analogy with the above that the cube was moving in space in a direction perpendicular to its three dimensions. This direction, then, would be the fourth perpendicular unknown to us in our space and in our geometry of three dimensions.

Further, we may determine a line as an infinite number of points; a square as an infinite number of lines; a cube as an infinite number of squares. By analogy with this we may determine the figure a4 as an infinite number of cubes.

Further, looking at the square we see nothing but lines; looking at the cube we see only its surfaces, or possibly even only one of its surfaces.

It is quite possible that the figure a4 would appear to us as a cube. To put it in a different way, the cube is what we see of the figure a4.

Further, a point may be determined as a cross-section of a line; a line as a cross-section of a surface; a surface as a cross-section of a solid. A three-dimensional body can therefore be determined as a cross-section of a four-dimensional body.

Generally speaking, in every four-dimensional body we shall see its three-dimensional projection or section. A cube, a square, a pyramid, a cone, a cylinder, may be projections or cross-sections of four-dimensional bodies unknown to us.

It was a letter written by N A Morosoff in 1891 to his fellow-prisoners in the fortress of Schlüsselburg. [N A Morosoff, a scientist by education, belonged to the revolutionary parties of the seventies and eighties. He was arrested in connection with the murder of the Emperor Alexander II and spent twenty-three years in prisons, chiefly in the fortress of Schlüsselburg. Liberated in 1905 he wrote several books, one on the Revelation of St John, another on Alchemy, on Magic, etc., which found fairly numerous readers in the period before the War. It was rather curious that the public liked in Morosoff's books not what he actually wrote, but what he wrote about. His real intentions were very limited and in strict accordance with the scientific ideas of the seventies. He tried to present "mystical subjects" rationally; for instance, he explained the Revelation as nothing but a description of a thunderstorm. But being a good writer, Morosoff gave a very vivid exposition of his themes, and sometimes he added little-known material. So his books produced a quite unexpected result, and many people became interested in mystical literature after reading Morosoff's books. After the revolution, Morosoff joined the Bolsheviks and remained in Russia. Although, so far as is known, he has not taken part in destructive work himself, he has written nothing more, and on solemn occasions expresses his official admiration of the Bolshevik régime. — PDO]

Morosoff's letter is of interest chiefly because it contains, in a very picturesque form, an exposition of the fundamental proposition of the method mentioned above of reasoning about the fourth dimension by means of analogies.

The first part of Morosoff's article is very interesting, but in his final conclusions as to what may exist in the domain of the fourth dimension, he deviates from the method of analogies and assigns to the fourth dimension the "spirits" which spiritualists evoke in their séances. And then, having denied the existence of spirits, he denies also the objective meaning of the fourth dimension.

It is generally supposed that fortress walls do not exist in the fourth dimension, and that was probably the reason why the fourth dimension was one of the favourite subjects of the conversations held in Schlüsselburg by means of tapping.

N A Morosoff's letter is an answer to the questions put to him in one of these conversations. He writes:

My dear friends, our short Schlüsselburg summer is nearing its end, and the dark mysterious autumn nights are coming. In these nights, spreading like a cloak over the roof of our prison and enveloping with impenetrable darkness our little island with its old towers and bastions, it would seem that the shadows of our friends and predecessors who perished here flit invisibly round these walls, look at us though the windows, and enter into mysterious communication with us who still live. And we ourselves, are we not but shadows of what we used to be? Are we not transformed into some kind of tapping spirits, conversing unseen with one another through the stone walls which divide us, like those that perform at spiritualistic séances.

All day long I have thought of your discussion of today about the fourth, the fifth, and other dimensions of the space of the Universe which are inaccessible to us. With all my power I have tried to imagine at least the fourth dimension of the world, the one in which, as metaphysicians affirm, everything that is under lock and key may suddenly appear open, and in which all confined paces can be entered by beings able to move not only along our three dimensions, but also along the fourth, to which we are unaccustomed.

You ask me for a scientific examination of the problem. Let us speak first of the world of only two dimensions; and later we will see whether it will give us the possibility of drawing certain conclusions about different worlds.

Let us take a certain plane — for instance, that which separates the surface of Lake Ladoga which surrounds us from the atmosphere above it in this quiet summer evening. Let us suppose that this plane is a separate world of two dimensions, peopled with its own beings, which can move only on this plane like the shadows of swallows and sea-gulls flitting in all directions over the smooth surface of the water which surrounds us, but remains for ever hidden from us behind these battlements.

Let us suppose that, having escaped from behind our Schlüsselburg bastions, you went for a bathe in the lake.

As beings of three dimensions you also have the two dimensions which lie on the surface of the water. You will occupy a definite place in the world of shadow beings. All the parts of your body above and below the level of the water will be imperceptible to them, and they will be aware of nothing but your contour, which is outlined by the surface of the lake. Your contour must appear to them as an object of their own world, only very astonishing and miraculous. The first miracle from their point of view will be your sudden appearance in their midst. It can be said with full conviction that the effect you would create would be in no way inferior to the unexpected appearance among ourselves of some ghost from the unknown world. The second miracle would be the surprising changeability of your external form. When you are immersed up to your waist your form will be for them almost elliptical, because only the line on the surface surrounding your waist and impenetrable for them will be perceptible for them. When you begin to swim, you will assume in their eyes the outline of a man. When you wade into a shallow place so that the surface on which they live will encircle your legs, you will appear to them transformed into two ring-shaped beings. If, desirous of keeping you in one place, they surround you on all sides, you can step over them in a way quite inconceivable to them. In their eyes you would be all-powerful beings — inhabitants of a higher world, similar to those supernatural beings about whom theologians and metaphysicians tell us.

Now if we suppose that apart from these two worlds, the plane world and the world we live in, there exists a world of four dimensions, superior to ours, it will become clear that in relation to us its inhabitants would be exactly the same as we are in relation to the inhabitants of a plane. They must appear in our midst in the same unexpected way and disappear from our world at their will, moving along the fourth or some other higher dimension.

In a word the analogy, so far, is complete. Further we shall find in the same analogy a complete refutation of all our hypotheses.

If indeed the beings of the four-dimensional world were not purely our invention, their appearance in our midst would be an ordinary everyday occurrence.

Further, Morosoff discusses whether we have any reason to suppose that "supernatural beings" really exist, and he comes to the conclusion that we have no grounds for such a hypothesis unless we are prepared to believe in fairy-tales.

The only indication, worthy of our attention, of the existence of such beings can be found, according to Morosoff, in the teachings of spiritualism. But his own experience in "spiritualism" convinced him that in spite of the strange phenomena that undoubtedly occur at spiritualistic séances, "spirits" take no part in them. So-called "automatic writing" usually cited as proof of the co-operation of intelligent forces of another world is, according to his observations, a result of thought-reading. Consciously or unconsciously, a "medium" "reads" the thoughts of those present and from these thoughts obtains the answers to their questions. Morosoff attended many séances, but never met with a case where there was anything in the answers received which were not known to any of the people present. Therefore, though not doubting the sincerity of the majority of spiritualists, Morosoff concludes that "spirits" have nothing to do with phenomena at séances.

His experience of spiritualism, he says, had finally convinced him many years previously that the phenomena which he assigned to the fourth dimension do not really exist. He says that at such spiritualistic séances, answers are given unconsciously by the actual people present, and that therefore all suppositions concerning the existence of the fourth dimension are pure imagination.

Morosoff describes how miraculous our three-dimensional bodies would seem to the plane beings, how these beings would not know whence our bodies came and whither they disappear like spirits from an unknown world.

But in reality are we not beings just as fantastic and changeable in our appearance for any stationary object, a stone or a tree? Further, do we not possess the properties of "higher beings" for animals? Are there no phenomena for us, for instance all the manifestations of life, about which we do not know whence they come nor whither they go; phenomena such as the appearance of a plant from a seed, the birth of living things, and the like; and further, the phenomena of nature, thunderstorms, rain, spring, autumn, which we can neither explain nor interpret. Is not each of these phenomena of nature taken separately something of which we can feel only a little, touch only a part, like the blind men in the old Eastern fable who each defined an elephant in his own way: one by its legs, another by its ears, a third by its tail.

Continuing Morosoff's reasonings concerning the relations between the world of three dimensions and the world of four dimensions, we have no grounds for looking for the latter only in the domain of "spiritualism".

Let us take a living cell. It may be exactly equal in length, breadth, and height to another, dead, cell. But there is something in the living cell which is lacking in the dead one, something we are unable to measure.

We say that it is "vital force", and try to explain it as a kind of motion. But in reality we do not explain anything by this, but only give a name to a phenomenon which remains inexplicable.

According to some scientific theories, vital force must be resolvable into physico-chemical elements, into simpler forces. But not one of these theories can explain how the one passes into the other and in what relation the one stands to the other. We are unable to express in a physico-chemical formula the simplest manifestations of life energy, and as long as we are unable to do so we have no right, in a strictly logical sense, to regard vital processes as identical with physico-chemical processes.

We may accept philosophical "monism", but we have no reasons for accepting the physico-chemical monism imposed on us from time to time which identifies vital and psychic processes with physico-chemical processes. Our mind may come in an abstract way to the conclusion of the unity of physico-chemical, vital, and psychic processes, but for science, for exact and concrete knowledge, these three classes of phenomena stand quite separate from one another.

For science, three classes of phenomena — mechanical force, vital force, and psychic force — pass into one another only partially, and apparently without any fixed or calculable proportions. Therefore, scientists will be justified in explaining vital and psychic processes as a kind of motion only when they have found means of transforming motion into vital and psychic energy and vice versa, and of calculating such a transformation. This means that such an affirmation will be possible only when it is known what number of calories contained in a definite quantity of coal is necessary for starting the life of one cell, or how many atmospheres of pressure are necessary for the formation of one thought or one logical deduction. As long as these are not known, physical, biological, and psychic phenomena, as studied by science, take place on different planes. Their unity can be surmised, but nothing can be affirmed positively.

If one and the same force acts in physico-chemical, vital, and psychic processes, it may be supposed that it acts in different spheres only partly contiguous with one another.

If science really possessed knowledge of at least vital and physico-chemical phenomena, it would be able to create living organisms. In this expectation there is nothing extravagant. People construct machines and apparati which are much more complicated externally than a "simple" one-cell organism, and yet they are unable to construct such an organism. This means that there is something in a living cell which does not exist in a lifeless machine. A living cell contains something which is lacking in a dead one, and we have every right to call this something both inexplicable and unmeasurable. In examining man, we have good reasons for putting to ourselves the question: which part of him is bigger, the measurable or the immeasurable?

But what real grounds has Morosoff for affirming so definitely that he has not this dimension?

Can he measure everything in himself? Two principal functions of man, life and thought, are in the domain of the unmeasurable.

We know so vaguely and so imperfectly what man really is, and we have in ourselves so much that is enigmatic and incomprehensible from the point of view of the geometry of three dimensions that we have no reason to deny the fourth dimension in denying "spirits". On the contrary, we have ample grounds for looking out for the fourth dimension precisely in ourselves.

We have to confess to ourselves clearly and definitely that we do not in the least know what man really is. For us he is an enigma, and we must accept this enigma as such.

The "fourth dimension" promises to explain something in this enigma. Let us try to see what the "fourth dimension" can give us if we approach it with the old methods but without the old prejudices for or against spiritualism. Let us again imagine a world of plane-beings possessing only two dimensions, length and breadth, and inhabiting a flat surface. [In these reasonings about imaginary worlds, I shall partly follow Hinton's plan, but this does not mean that I share all Hinton's opinions. — PDO]

Let us imagine, on this surface, living beings having the shape of geometrical figures and capable of moving in two directions.

At the very beginning of the examination of the conditions of life of these flat beings, we come at once face to face with a very interesting fact.

These beings will be able to move in only two directions on their plane. They will be unable to rise above this plane or to leave it. In the same way they will be unable to see or feel anything lying outside their plane. If one of these beings rises above the plane, he will completely pass away from the world of other beings similar to it, will vanish, disappear — no one knows whither.

If we suppose that the organs of vision of these beings are situated in their edges, on their outer lines, then they will not be able to see the world lying outside their plane at all. They will see only lines lying on their plane. They will see each other not as they really are, i.e., in the shape of geometrical figures, but only in the form of lines. It is also very important to realise that all lines, whether straight, curved, or with angles, will appear to them alike; they will not be able to see any difference in the lines themselves. However, at the same time, the lines will differ for them by strange properties which they will probably call the motion or the vibration of lines.

The centre of a circle will be inaccessible to them. They will be quite unable to see it. In order to reach the centre of a circle, a two-dimensional being will have to dig or cut his way through the mass of the flat figure having the thickness of one atom. The process of digging will appear to him as altering the line of the circumference.

If a cube is placed on his plane, then this cube will appear to him in the form of four lines bounding the square touching his plane. Of the whole cube only this square will exist for him. He will be unable even to imagine the rest of the cube. The cube will not exist for him.

If several bodies come into contact with his plane, for a plane-being there will exist in each of them only one surface which has come into contact with his plane. This surface, that is, the lines bounding it, will appear to him as an object of his own world.

If through his space, that is, through his plane, there passes a multicoloured cube, the passage of the cube will appear to him as a gradual change in the colour of the lines bounding the square which lies on his plane.

If we suppose that the plane-being is made able to see with his flat side, the one facing our world, it is easy to imagine what a wrong conception of our world he will receive.

The whole Universe will appear to him in the form of a plane. It is very probable that he will call this plane aether. Consequently, he will either completely deny all phenomena which take place outside his plane, or regard them as happening on his own plane, in his aether. Unable to explain on his plane all the phenomena observed by him, he may call them miraculous, lying above his understanding, beyond his space, in the "third dimension".

Having observed that the inexplicable events occur in a certain consecutiveness, in a certain dependence on some laws, the plane-being will cease to consider them miraculous and will attempt to explain them by means of more or less complicated hypotheses.

The appearance of the dim idea of another parallel plane will be for a plane-being the first step towards the right understanding of the Universe. He will then imagine all the phenomena he is unable to explain on his own plane as occurring on that parallel plane. At this stage of development the whole of our world will appear to him as plane and parallel to his own plane. Neither relief nor perspective will exist for him as yet. A mountain landscape will appear to him as a flat photograph. His conception of the world will certainly be very poor and full of errors. The big things will be taken for the small and the small things for the big, and all together, whether near or far, will appear to him equally remote and inaccessible.

Having recognised that there is a world parallel to his plane world, the two-dimensional being will say that he knows nothing of the true nature of the relations between these two worlds.

In the parallel world there will be much that will appear inexplicable for a two-dimensional being: say, a lever, or a couple of wheels on an axle. Their action will appear quite inconceivable to the plane-being, whose conception of laws of motion is limited to motion on a plane. It is quite possible that this phenomenon will be considered supernatural and later will be called, in a more scientific way, "super-physical".

In studying these super-physical phenomena, the plane-being may stumble upon the idea that a lever, or wheels, contain something unmeasurable, but nevertheless existing.

From this there is only one step to the hypothesis of the third dimension. The plane-being will base this hypothesis precisely on inexplicable facts, such as the rotation of wheels. He may ask himself whether the inexplicable may not really be the unmeasurable, and then begin gradually to elucidate for himself the physical laws of three-dimensional space. But he will never be able to prove mathematically the existence of this third dimension, because all his geometrical speculations will proceed only on a plane, in two dimensions, and therefore he will project on to a plane the results of his mathematical conclusions thus destroying all their meaning.

The plane-being will be able to obtain his first notion of the nature of the third dimension merely by means of logical reasonings and comparisons. That means that in examining the inexplicable that lies in the flat photograph (for him representing our world) the plane-being may arrive at the conclusion that many phenomena are inexplicable for him, because in the objects causing these phenomena there may be a certain difference which he does not understand and cannot measure.

In the same way the plane-being may come to the recognition that he himself must necessarily possess the third dimension.

After arriving at the conclusion that a real body of two dimensions cannot exist, that this is but an imaginary figure, the plane-being will have to say to himself that, since the third dimension exists, he must himself possess this third dimension because otherwise, having only two dimensions, he would be but an imaginary figure, that is, exist only in somebody's mind.

The plane-being will reason in the following way: "If the third dimension exists, I am either a being of three dimensions or I do not exist in reality but exist only in somebody's imagination".

In reflecting why he does not see his third dimension, the plane-being may come upon the thought that his extension along the third dimension, just like the extension of other bodies along the third dimension, is very small. These reflections may bring the plane-being to the conclusion that for him the question of the third dimension is connected with the problem of small magnitudes.

In investigating the world in a philosophical way, the plane-being will from time to time doubt his own reality and the reality of everything surrounding him.

He may then think that his conception of the world is wrong and that he does not even see it as it really is. Reasonings about things as they appear and about things as they are may follow from this. The plane-being may think that in the third dimension things must appear as they are, i.e., that he will see in the same things more than he saw in two dimensions.

Verifying all these reasonings from our point of view, that is, from the point of view of beings of three dimensions, we must recognise that all the conclusions of the plane-being are perfectly right and lead him to a right understanding of the world and to the recognition, though theoretical in the beginning, of the third dimension.

We may profit by the experience of the plane-being and try to find whether there is anything in the world towards which we are in the same relation as the plane-being is towards the third dimension.

In examining the physical conditions of the life of man, we find in them an almost complete analogy with the conditions of the plane-being who begins to be aware of the third dimension.

At first man considers the invisible as miraculous and supernatural. Gradually, with the evolution of knowledge, the idea of the miraculous becomes less and less necessary. Everything within the sphere accessible to observation (and unfortunately far beyond it) is regarded as existing according to certain definite laws, as the result of certain definite causes. But the causes of many phenomena remain hidden, and science is forced to limit itself to a classification of these inexplicable phenomena.

In studying the character and properties of the "inexplicable" in different branches of our knowledge, in physics and chemistry, in biology, and in psychology, we can arrive at certain general conclusions concerning the character of the inexplicable. That means we can formulate the problem as follows: is not the inexplicable a result of something, "unmeasurable" for us, which exists in those things which, as it appears to us, we can measure fully, as well as in things which, as it appears to us, can have no measurement?

We can think that this very inexplicability may be the result of the fact that we examine and attempt to explain them on our plane, i.e., within our three-dimensional space, while really they occur outside our plane, in the domain of a higher dimension. To put it differently, are we not in the position of the plane-being trying to explain as happening on a plane phenomena that take place in three-dimensional space?

There is a great deal that confirms the probability of such a supposition.

It is quite possible that many inexplicable phenomena are inexplicable only because we wish to explain them on our plane, i.e., within our three-dimensional space, while really they occur outside our plane, in the domain of higher dimensions.

Having come to the conclusion that we are surrounded by the world of the unmeasurable, we must admit that, until now, we have had an entirely wrong conception of the objects of our world.

We knew before that we see things and represent them to ourselves not as they really are. Now we may say more definitely that we do not see in things that part of them which is immeasurable for us, lying in the fourth dimension.

This last conclusion brings us to the idea of the difference between the imaginary and the real.

We saw that the plane-being, having arrived at the idea of the third dimension, must conclude that, if there are three dimensions, a real body of two dimensions cannot exist. A two-dimensional body would be only an imaginary figure, a section of a body of three dimensions or its projection in two-dimensional space.

Admitting the existence of the fourth dimension, we must recognise in the same way that if there are four dimensions, a real body of three dimensions cannot exist. A real body must possess at least a very small extension along the fourth dimension, otherwise it will be only an imaginary figure, the projection of a body of four dimensions in three-dimensional space, like a "cube" drawn on paper.

In this way we must come to the conclusion that there may exist a cube of three dimensions and a cube of four dimensions, and that only the cube of four dimensions will really, actually, exist.

Examining man from this point of view, we come to very interesting deductions.

If the fourth dimension exists, one of two things is possible. Either we ourselves possess the fourth dimension, i.e., there are beings of four dimensions, or we possess only three dimensions and in that case do not exist at all.

If the fourth dimension exists while we possess only three, it means that we have no real existence, that we exist only in somebody's imagination, and that all our thoughts, feelings, and experiences take place in the mind of some other higher being who visualises us. We are but products of his mind, and the whole of our universe is but an artificial world created by his fantasy.

If we do not want to agree with this, we must recognise ourselves as beings of four dimensions.

At the same time we must recognise that our own fourth dimension, as well as the fourth dimension of the bodies surrounding us, is known and felt by us only very little and that we only guess its existence from observations of inexplicable phenomena.

Such blindness in relation to the fourth dimension may be caused by the fact that the fourth dimension of our own bodies and other objects of our world is too small and inaccessible to our organs of sense, or to the apparatus which widens the sphere of our observation, exactly in the same way as the molecules of our bodies and many other things are inaccessible to immediate observation. As regards objects possessing a greater extension in the fourth dimension, we feel them at times in certain circumstances, but refuse to recognise them as really existing.

These last considerations give us sufficient grounds for believing that, at least in our physical world, the fourth dimension must refer to the domain of small magnitudes.

Even if we leave aside other defects of our perception and regard its activity only in relation to geometry, we shall have to admit that we see everything as very unlike what it really is.

We do not see bodies: we see nothing but surfaces, sides, and lines. We never see a cube: we see only a small part of it, never see it from all sides at once.

From the fourth dimension it must be possible to see the cube from all sides at once and from within, as though from its centre.

The centre of a sphere is inaccessible to us. To reach it we must dig our way through the mass of the sphere, i.e., act in exactly the same way as the plane-being with regard to the circle. The process of cutting through will in that case appear to us as a gradual change in the surface of the sphere.

The complete analogy of our relation to the sphere with the relation of the plane-being to the circle gives us grounds for thinking that in the fourth dimension, or along the fourth dimension, the centre of the sphere is as easily accessible as is the centre of the circle in the third dimension. In other words, we have a right to suppose that in the fourth dimension it is possible to reach the centre of the sphere from some region unknown to us, along some incomprehensible direction, the sphere itself remaining intact. The latter circumstance would appear to us a kind of miracle: but just as miraculous, to the plane-being, must appear the possibility of reaching the centre of the circle without disturbing the line of its circumference, without breaking up the circle.

Continuing to imagine further the properties of vision or perception in the fourth dimension, we shall have to recognise that not only in a geometrical sense, but also in many other senses, it is possible from the fourth dimension to see in objects of our world much more than we do see.

Prof. Helmholtz once said about our eye that if an optician sent him so badly made an instrument, he would never accept it.

Undoubtedly our eye does not see a great many things which exist. But if in the fourth dimension we see without the aid of such an imperfect instrument, we should be bound to see much more: that is, to see what is invisible for us now and to see everything without that net of illusions which veils the whole world from us and makes its outward aspect very unlike what it really is.

The question may arise why we should see in the fourth dimension without the aid of eyes, and what it means.

It will be possible to answer these questions definitely only when it is definitely known that the fourth dimension exists and when it is known what it really is. But so far it is possible to consider only what might be in the fourth dimension, and therefore there cannot be any final answer to these questions. Vision in the fourth dimension must be effected without the help of eyes. The limits of eyesight are known, and it is known that the human eye can never attain the perfection even of the microscope or telescope. But these instruments with all the increase of the power of vision which they afford do not bring us in the least nearer to the fourth dimension. So it may be concluded that vision in the fourth dimension must be something quite different from ordinary vision. But what can it actually be? Probably it will be something analogous to the "vision" by which a bird flying over Northern Russia "sees" Egypt, whither it migrates for the winter; or to the vision of a carrier pigeon which "sees", hundreds of miles away, its loft, from which it has been taken in a closed basket; or to the vision of an engineer making the first calculations and first rough drawings of a bridge, who "sees" the bridge and the trains passing over it; or to the vision of a man who, consulting a time-table, "sees" himself arriving at the station of departure and his train arriving at its destination.

Now, having outlined certain features of the properties which vision in the fourth dimension should possess, we must endeavour to define more exactly what we know of the phenomena of that world.

Again making use of the experience of the two-dimensional being, we must put to ourselves the question: are all the "phenomena" of our world explicable from the point of view of physical laws?

There are so many inexplicable phenomena around us that merely by being too familiar with them we cease to notice their inexplicability and, forgetting it, we begin to classify these phenomena, give them names, and create out of them a separate world which is regarded as parallel to the "explicable".

Our relation to the psychic, the difference which exists for us between the physical and the psychic, shows that psychic phenomena should be assigned to the domain of the fourth dimension. [The expression "psychic" phenomena is used here in its only possible sense of psychological or mental phenomena, that is, those which constitute the subject of psychology. I mention this because in spiritualistic and theosophical literature the word "psychic" is used for the designation of supernormal or super-physical phenomena. — PDO] In the history of human thought the relation to the psychic is very similar to the relation of the plane-being to the third dimension. Psychic phenomena are inexplicable on the "physical plane", therefore they are regarded as opposite to the physical. But their unity is vaguely felt, and attempts are constantly made to interpret psychic phenomena as a kind of physical phenomena, or physical phenomena as a kind of psychic phenomena. The division of concepts is recognised to be unsuccessful, but there are no means for their unification.

In the first place the psychic is regarded as quite separate from the body, as a function of the "soul", unsubjected to physical laws. The soul lives by itself, and the body by itself, and the one is incommensurable with the other. This is the theory of naïve dualism or spiritualism. The first attempt at an equally naïve monism regards the soul as a distinct function of the body. It is then said that "thought is a motion of matter". Such was the famous formula of Moleschott.

Both views lead into blind alleys: the first, because the obvious interdependence of physiological and psychic processes cannot be disregarded; the second, because motion still remains motion and thought remains thought.

The first view is analogous to the denial by the two-dimensional being of any physical reality in phenomena which happen outside his plane. The second view is analogous to the attempt to consider as happening on a plane phenomena which happen above it or outside it.

The next step is the hypothesis of a parallel plane on which all the inexplicable phenomena take place. But the theory of parallelism is a very dangerous thing.

The plane-being begins to understand the third dimension when he begins to see that what he considered parallel to his plane may actually be at different distances from it. The idea of relief and perspective will then appear to his mind, and the world and things will take for him the same form as they have for us.

We shall understand more correctly the relation between physical and psychic phenomena when we clearly understand that the psychic is not always parallel to the physical and may be quite independent of it. Parallels which are not always parallel are evidently subject to laws that are incomprehensible to us, to laws of the world of four dimensions.

At the present day it is often said: we know nothing about the exact nature of the relations between physical and psychic phenomena; the only thing we can affirm and which is more or less established is that for every psychic process, thought, or sensation, there is a corresponding physiological process which manifests itself in at least a feeble vibration in nerves and brain fibre and in chemical changes in different tissues. Sensation is defined as the consciousness of a change in the organs of sense. This change is a certain motion which is transmitted into brain centres, but in what way the motion is transformed into a feeling or a thought is not known.

The question arises: is it not possible to suppose that the physical is separated from the psychic by four-dimensional space, i.e., that a physiological process, passing into the domain of the fourth dimension, produces there effects which we call feeling or thought?

On our plane, i.e., in the world of motion and vibrations accessible to our observation, we are unable to understand or to determine the action of a lever or the motion of a pair of wheels on an axle.

At one time the ideas of E Mach, expounded chiefly in his book Analysis of Sensations and Relations of the Physical to the Psychic, were in great vogue. Mach absolutely denies any difference between the physical and the psychic. In his opinion all the dualism of the usual view of the world resulted from the metaphysical conception of the "thing in itself" and from the conception (an erroneous one according to Mach) of the illusory character of our cognition of things. In Mach's opinion we can perceive nothing wrongly. Things are always exactly as they appear to be. The concept of illusion must disappear entirely. Elements of sensations are physical elements. What are called "bodies" are only complexes of elements of sensations: light sensations, sound sensations, sensations of pressure, etc. Mental images are similar complexes of sensations. There exists no difference between the physical and the psychic: both the one and the other are built up of the same elements (of sensations). The molecular structure of bodies and the atomic theory are accepted by Mach only as symbols, and he denies them all reality.

In this way, according to Mach's theory, our psychic apparatus builds the physical world. A "thing" is only a complex of sensations.

But in speaking of the theories of Mach it is necessary to remember that the psychic apparatus builds only the "forms" of the world (i.e., makes the world such as we perceive it) out of something else which we shall never attain. The blue of the sky is unreal, the green of the meadows is unreal; these "colours" belong to the reflected rays. But evidently there is something in the "sky", i.e., in the air of our atmosphere, which makes it appear blue, just as there is something in the grass of the meadow which makes it appear green.

Without this last addition a man might easily have said, on the basis of Mach's ideas: this apple is a complex of my sensations, therefore it only seems to exist, but does not exist in reality.

This would be wrong. The apple exists. A man can, in a most real way, become convinced of it. But it is not what it appears to be in the three-dimensional world.

No obstacles or distances exist for it. It penetrates impenetrable objects, visualises the structure of atoms, calculates the chemical composition of stars, studies life on the bottom of the ocean, the customs and institutions of a race that disappeared tens of thousands of years ago....

No walls, no physical conditions, restrain our fantasy, our imagination.

Did not Morosoff and his comrades fly in their imagination far beyond the bastions of Schlüsselburg?

Did not Morosoff himself in his book, Revelation in Tempest and Thunderstorm, travel through space and time when, as he was reading Revelations in the Alexeivsky ravelin of the Petropavlovsky Fortress, he saw thunder clouds scudding over the Isle of Patmos in the Greek Archipelago at five o'clock in the afternoon of 30 September in the year 395 CE?

Do we not in sleep live in a fantastic fairy kingdom where everything is capable of transformation, where there is no stability belonging to the physical world, where one man can become another or two men at the same time, where the most improbable things look simple and natural, where events often occur in inverse order from end to beginning, where we see the symbolical images of ideas and moods, where we talk with the dead, fly in the air, pass through walls, are drowned or burnt, die, and remain alive?

All this taken together shows us that we have no need to think that the spirits which appear or fail to appear at spiritualistic séances must be the only possible beings of four dimensions. We may have very good reason for saying that we are ourselves beings of four dimensions and are turned towards the third dimension with only one of our sides, i.e., with only a small part of our being. Only this part of us lives in three dimensions, and we are conscious only of this part as our body. The greater part of our being lives in the fourth dimension, but we are unconscious of this greater part of ourselves. Or it would be still more true to say that we live in a four-dimensional world, but are conscious of ourselves only in a three-dimensional world. This means that we actually live in one kind of conditions, but imagine ourselves to be in another.

The conclusions of psychology bring us to the same idea, but by a different road. Psychology comes, though very slowly, to recognition of the possibility of awakening our consciousness, i.e., the possibility of a particular state of it, when it sees and feels itself in a real world having nothing in common with this world of things and phenomena — in a world of thoughts, mental images, and ideas.

Consequently, if we suppose that from each point of the cube there is drawn a line which this movement must follow, the combination of these lines will then form the projection of a body of four dimensions. This body, that is, the tesseract, as was found before, can be regarded as an infinite number of cubes growing, as it were, out of the first cube.

Let us see now whether we know of any examples of such motion, which implies the motion of all points of the given cube.

Molecular motion, that is, the motion of minute particles of matter, which is increased by heating and lessened by cooling, is the most appropriate example of motion along the fourth dimension, in spite of all the erroneous ideas of physics with regard to this motion.

In an article entitled May We Hope to See Molecules? [in the review Naoutchnoye Slovo, February, 1903 — PDO] Prof. Goldgammer writes that, according to modern views, molecules are bodies the lineal section of which is something between one millionth and one ten-millionth part of a millimetre. It has been calculated that one milliardth part of a cubic millimetre, that is, one cubic micron, at a temperature of 0°C. and at normal pressure contains about 30 million molecules of oxygen.

"Molecules move very fast; thus under normal conditions the majority of molecules of oxygen have the velocity of about 450 metres per second. In spite of their great velocities, molecules do not disperse in all directions instantaneously because every moment they collide with one another and so change the direction of their motion. Owing to this the path of a molecule has the aspect of a very entangled zigzag, and a molecule actually 'Marks time', as it were, on one spot."

Leaving aside for a moment the entangled zigzag and the theory of colliding molecules (Brownian movement), we must try to find what results are produced in the visible world by molecular motion.

In order to find an example of motion along the fourth dimension we must admit that the expansion and contraction of bodies come nearest to the indicated conditions.

Expansion of gases, liquids, and solids means that molecules retreat from one another. Contraction of solids, liquids, and gases means that the molecules approach one another. The distance between them diminishes. There is space here and there are distances.

Is it not possible that this space lies in the fourth dimension?

A movement in this space means that all the points of the given geometrical body, that is, all the molecules of the given physical body, move.

The figure resulting from the movement of a cube in space when the cube expands will have the form of a cube, and we can imagine it as an infinite number of cubes.

Is it right to suppose that the assemblage of lines drawn from every point of a cube, interior as well as exterior, the lines along which the points approach one another or retreat from one another, constitutes the projection of a four-dimensional body?

In order to answer this, it is necessary to determine what these lines are and what this direction is.

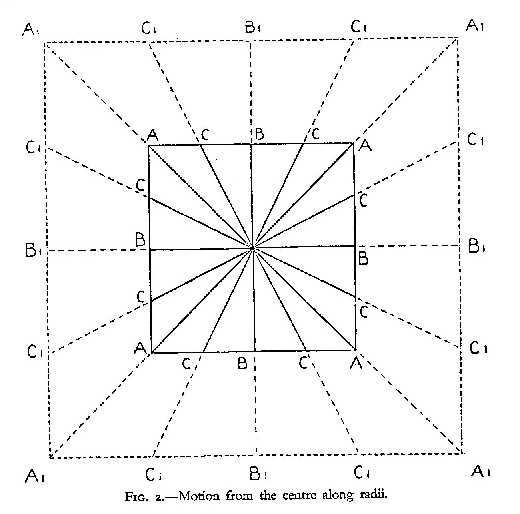

These lines connect all the points of the given body with its centre. Consequently the direction of the movement indicated will be from the centre along the radii.

In investigating the paths of the movements of the points (or molecules) of a body in case of expansion and contraction, we find in them many interesting features.

We cannot see the distance between molecules. We cannot see it in the case of solids, liquids, and gases because it is extremely small, and in the case of highly rarefied matter as, for instance, that in Crookes tubes, where this distance is probably increased to the proportions perceptible for us or for our apparatus, we cannot see it because the particles themselves, the molecules, are too small to be accessible to our observation. In the above-mentioned article, Prof. Goldgammer states that given certain conditions, molecules could be photographed if they could be made luminous. He writes that when the pressure in Crookes tubes is reduced to one-millionth part of an atmosphere, one cubic micron will contain only 30 molecules of oxygen. If they were luminous they could be photographed on a screen.

To what extent this photography is really possible is another question. For the present argument, a molecule as a real quantity in relation to a physical body can represent a point in its relation to a geometrical body.

All bodies must necessarily consist of molecules; consequently they must possess a certain, though a very small, dimension of intermolecular space. Without this we cannot conceive a real body, and can conceive only imaginary geometrical bodies. A real body consists of molecules and possesses a certain inter-molecular space.

This means that the difference between a cube of three dimensions, a3, and a cube of four dimensions, a4, will be that a cube of four dimensions consists of molecules, whereas a cube of three dimensions in reality does not exist and is only a projection of a four-dimensional body in three-dimensional space.

In expanding or contracting, that is, in moving along the fourth dimension, if the preceding arguments are admitted, a cube or sphere remains for us all the time a cube or sphere, changing only in size. Hinton quite rightly observed in one of his books that the passing of a cube of higher dimensions transversely to our space would appear to us as a change in the properties of the matter of the cube before us. He also says that the idea of the fourth dimension ought to have arisen from observation of a series of progressively growing or diminishing spheres or cubes. This last idea brings him quite near to the right definition of motion in the fourth dimension.

On the whole, Hinton stands so near to the correct solution of the problem of the fourth dimension that he sometimes guesses the place of the "fourth dimension" in life, although he cannot determine this place exactly. Thus he says that the symmetry of the structure of living organisms can be explained only by the movement of their particles along the fourth dimension.

There exists indeed in nature a very interesting phenomenon which gives us perfectly correct diagrams of the fourth dimension. It is necessary only to know how to read these diagrams. They are seen in the fantastically varied, but always symmetrical, shapes of snowflakes, and also in the designs of flowers, stars, ferns, and lacework which frost makes on window panes. Drops of water settling from the air on to a cold pane, or on to the ice already formed upon it, begin instantaneously to freeze and expand, leaving traces of their motion along the fourth dimension in the shape of intricate designs. These frost drawings on window panes, as well as the designs of snow-flakes, are figures of the fourth dimension, the mysterious a4. The motion of a lower figure to obtain a higher one, as imagined in geometry, is here actually realised, and the resulting figure, in effect, represents the trace left by the motion of the lower figure, because the frost preserves all the stages of the expansion of freezing drops of water.

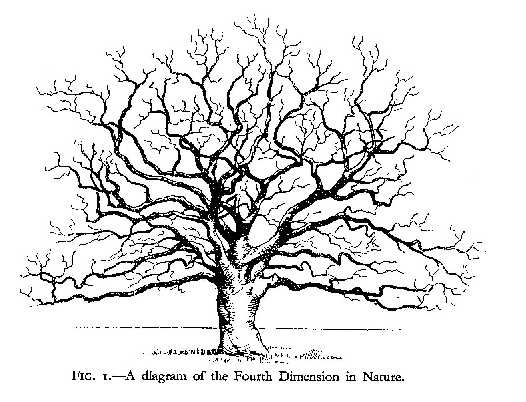

Forms of living bodies, living flowers, living ferns, are created according to the same principles, though in a more complex order. The outline of a tree gradually spreading into branches and twigs is, as it were, a diagram of the fourth dimension, a4.