Book 18 — A New Model of the Universe

by P D Ouspensky

Chapter III — Superman

Side by side with the idea of hidden knowledge there runs through the whole history of human thought the idea of superman.

The idea of superman is as old as history. Through hundreds of centuries, humanity has lived with the idea of superman. Sayings and legends of all ancient peoples are full of images of a superman. Heroes of myths, Titans, demigods, Prometheus who brought fire from heaven; prophets, messiahs, and saints of all religions; heroes of fairy tales and epic songs; knights who rescue captive maidens, awaken sleeping beauties, vanquish dragons, and fight giants and ogres — all these are images of a superman.

Popular wisdom of all times and all peoples has always understood that man, as he is, cannot arrange his own life by himself; popular wisdom has never regarded man as the crowning achievement of creation. It has always understood the place of man, and always accepted and admitted the thought that there can and must be beings who, though human, are also much higher, stronger, more complex, more "miraculous", than ordinary man. It is only the opaque and sterilised thought of the last centuries of European culture which has lost touch with the idea of superman and put as its aim man as he is, as he always was and always will be. And in this comparatively short period of time, European thought so thoroughly forgot the idea of superman that when Nietzsche threw this idea out to the West, it appeared new, original, and unexpected. In reality this idea has existed from the very beginning of human thought known to us.

After all, superman has never completely vanished in modern Western thought. What, for instance, is the Napoleonic legend and what are all similar legends but attempts to create a new myth of superman? The masses in their own way still live with the idea of superman; they are never satisfied with man as he is; and the literature supplied to the masses invariably gives them a superman. What indeed is the Count of Monte Cristo, or Rocambole, or Sherlock Holmes, but a modern expression of the same idea of a strong, powerful being against whom ordinary men cannot fight, who surpasses them in strength, bravery and cunning, and whose power always has in it something mysterious, magical, miraculous.

Table of Contents

If we try to examine the forms in which the idea of superman has been expressed in human thought in different periods of history, we shall see that it falls into several definite categories.

The first idea of superman pictured him in the past, connected him with the legendary Golden Age. The idea has always been one and the same. People dreamt of, or remembered, times long past when their life was governed by supermen who struggled against evil, upheld justice, and acted as mediators between men and the Deity, governing them according to the will of the Deity, giving them laws, bringing them commandments. The idea of theocracy is always connected with the idea of superman. God, or gods, whatever they were called, always governed people with the help and mediation of supermen — prophets, chiefs, kings of a mysterious superhuman origin. Gods could never deal directly with men. Man never was and never considered himself sufficiently strong to look upon the face of the Deity and receive laws directly. All religions begin with the advent of a superman. "Revelation" always comes through a superman. Man has never believed himself able to do anything of real significance.

But dreams of the past could not satisfy man; he began to dream of the future, of the time when a superman would come again. From this a new conception of superman resulted.

People began to expect the superman. He was to come, arrange their affairs, govern them, teach them to obey the law or bring them a new law, a new teaching, a new knowledge, a new truth, a new revelation. The superman was to come to save men from themselves, as well as from the evil forces surrounding them. Almost all religions contain such an expectation of a superman, an expectation of a prophet, of a messiah.

In Buddhism the idea of superman completely replaces the idea of the Deity: Buddha is not God; he is only a superman.

The idea of superman has never been absent from the consciousness of mankind. The image of a superman was shaped out of very varied elements. At times it received a strong admixture of popular fantasy which brought into it conceptions arising from the personification of nature, of fire, of thunder, of the forest, of the sea; the same fantasy sometimes united in a single image vague rumours concerning some distant people, either more savage or, on the contrary, more civilised.

Thus, travellers' tales of cannibals were united in the imagination of the ancient Greeks into the image of the Cyclops Polyphemus, who devoured the companions of Odysseus. An unknown people, an unknown race, was very easily transformed in myths into a single superhuman being.

Thus, the idea of superman in the past, or in the present in unknown countries, was always vivid and rich in content. But the idea of a superman as a prophet or messiah, of the superman whom people were expecting, was always very obscure. People had a very dim conception of superman; they did not understand in what way superman should differ from ordinary man.

And when superman came, people stoned him or crucified him because he did not fulfil their expectations. Nevertheless, the idea did not die out and, even in an indistinct and confused form, it served as a measure by which the nothingness of man was measured. But the idea was gradually forgotten when man began to lose the realisation of his nothingness.

Table of Contents

For the modern scientific view of the world the idea of superman stands apart, as a sort of philosophical curiosity unconnected with anything else. Modern Western thought does not know how to depict the idea of superman in the right tones. It always distorts this idea; it is always afraid of the final deductions from it and, in its theories of the future, it denies any connection with it.

This attitude towards the idea of superman is based upon a wrong understanding of the ideas of evolution. The chief defects of the modern understanding of evolution have been pointed out in an earlier chapter.

"Superman", if he ever enters scientific thought, is regarded as the product of the evolution of man, although as a rule this term is not used at all and is replaced by the term "a higher type of man". In this connection, evolutionary theories became the basis of a naïve optimistic view of life and of man. It is as though people said to themselves: now that evolution exists and now that science recognises evolution, it follows that all is well and must in future become still better. In the imagination of the modern man reasoning from the point of view of the ideas of evolution, everything should have a happy ending. A story should necessarily end in a wedding. It is precisely here that lies the chief mistake with regard to evolution. However it is understood, evolution is not assured for anyone or for anything. The theory of evolution means only that nothing stands still, nothing remains as it was, everything inevitably goes either up or down, and not at all necessarily up. To think that everything necessarily goes up is the most fantastic conception of the possibilities of evolution.

Table of Contents

All the forms of life we know are the result of either evolution or degeneration; but we cannot discriminate between these two processes, and we very often mistake the results of degeneration for the results of evolution. Only in one respect do we make no mistake: we know that nothing remains as it was. Everything "lives", everything is transformed.

Man also is transformed, but whether he goes up or down is a big question. Moreover, evolution in the true sense of the word has nothing in common with the anthropological change of the type, even if we consider such a change as established. Nor has evolution anything in common with the change of social forms, customs, and laws, nor with the modification and "evolution" of forms of slavery or means of warfare. Evolution towards superman is the creation of new forms of thinking and feeling, and the abandonment of the old forms.

Moreover, we must remember that the development of a new type is accomplished at the expense of the old type, which is made to disappear by the same process. The new type being created out of an old one overcomes it, so to speak, conquers it, occupies its place.

Nietzsche's Zarathustra speaks of this in the following words:

I teach you the superman. Man is something that has to be surmounted. What have you done to surmount man?

What is the ape to man? A laughing stock or a sore disgrace! And just the same result shall man be to the superman — a laughing stock or a sore disgrace.

Even the wisest of you is but a discord, and a hybrid of plant and phantom.

Man is a rope over an abyss. A dangerous crossing, a dangerous wayfaring, a dangerous looking back, a dangerous trembling and halting.

What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not a goal; what is loveable in man is that he is an over-going and a down-going.

— F Nietzsche: Thus Spake Zarathustra (Thomas Common, 1908).

These words of Zarathustra have not entered into our usual thinking. When we picture a superman to ourselves, we accept and approve in him just those sides of human nature which should be discarded on the way.

Superman appears to us as a very complicated and contradictory being. In reality superman must be a clearly defined being. He cannot have within him that eternal inner conflict, that painful inner division, which men continually feel, and which they ascribe even to gods.

At the same time there cannot be two opposite types of superman. Superman is the result of a definite movement, of a definite evolution.

In ordinary thinking superman appears as a hypertrophied man with all sides of his nature greatly exaggerated. This, of course, is quite impossible, because one side of human nature can develop only at the expense of other sides, and superman can be the expression of only one, and of one very definite, side of human nature.

Table of Contents

These wrong conceptions of superman are due in a considerable degree to the fact that ordinary thought considers man to be a much more finished type than he really is.

The same naïve view of man lies at the base of all existing social sciences and theories. All these theories have in view only man and his future. They either endeavour to foresee the possible future of man or recommend the best methods, from their point of view, of giving man all the happiness possible, of freeing man from unnecessary suffering, from injustice, and so on. But people do not see that attempts at a forcible application of such theories to life result only in increasing the amount of suffering and injustice. In trying to foresee the future all these theories want to make life serve and obey man, and in doing so they do not take into account the real fact that man must himself change. Believing in these theories, people want to build without keeping in mind that a new master must come and that a new master may not at all like what they have built or have begun to build.

Man is pre-eminently a transitional form, constant only in his contradictions and inconstancy — moving, becoming, changing, before our eyes. Even without any special study, it is perfectly clear that man is a quite unfinished being, differing today from what he was yesterday, and differing tomorrow from what he is today.

So many opposing principles struggle in man that a harmonious co-ordination of them is quite impossible. This explains why a "positive" type of man is impossible. The soul of man is far too complex a combination for all the voices shouting at it to become united into one harmonious choir. All the kingdoms of nature live in man. Man is a little universe. In him proceed continual death and continual birth, the incessant swallowing of one being by another, the devouring of the weaker by the stronger, evolution and degeneration, growing and dying out. Man has within him everything from a mineral to God. And the desire of God in man, that is, the directing forces of his spirit, conscious of its unity with the infinite consciousness of the Universe, cannot be in harmony with the inertia of a stone, with the inclination of particles for crystallisation, with the sleepy flow of sap in a plant, with the plant's slow turning towards the Sun, with the call of the blood in an animal, with the "three-dimensional" consciousness of man, which is based on his separating himself from the world, on his opposing his own "I" to the world, and on his recognising as reality all apparent forms and divisions.

The more man develops inwardly, the more strongly he begins to feel the different sides of his soul simultaneously; the more strongly he feels himself, the more strongly grows within him the desire to feel more and more; and at last he begins to desire so many things that he is never able to obtain at once all that he desires; and at the same time, his imagination carries him in different directions. One life is no longer sufficient for him; he needs ten, twenty lives at one time. He needs to be simultaneously in different places, with different people, in different circumstances; he wants to reconcile the irreconcilable and combine the uncombinable. His spirit does not wish to reconcile itself to the limitations of body and matter, to the limitations of time and space. His imagination travels infinitely far beyond all possibilities of realisation, just as his emotional feeling travels infinitely far beyond the formulations and attainments of his intellect.

Man outruns himself, but at the same time begins to be satisfied with imagination only, without attempts at realisation. In his rare attempts at realisation, he does not see that he obtains things diametrically opposed to what he thinks he is approaching.

Table of Contents

The complicated system of the human soul often appears as dual, and there are serious grounds for such a view. There live in every man, as it were, two beings, one comprising the mineral, vegetable, animal and human "time and space" world, and the other belonging to some other world. One is the being of "the past", the other the being of "the future". But which is the being of the past and which the being of the future we do not yet know. The past and the future find themselves in eternal struggle and eternal conflict in the soul of man. It may be said without the slightest exaggeration that the soul of man is the battlefield of the past and the future.

Nietzsche's Zarathustra says these interesting words:

I am of today and heretofore, but something is in me that is of the morrow and of the day following and the hereafter. — Thus Spake Zarathustra.

But Zarathustra speaks not of the conflict, he speaks of the fullness which includes today and heretofore, tomorrow and hereafter, a fullness which comes when contradictions, multiplicity, and duality have been conquered.

The necessity for struggle against man for the attainment of superman is what modern thought utterly refuses to admit. This idea entirely disagrees with the exaltation of man and his weaknesses which is so characteristic of our times.

Table of Contents

But this does not mean that the idea of superman plays no rôle in our time. If certain schools of modern thought reject the idea of superman or are afraid of it, others, on the contrary, are entirely based on the idea and cannot exist without it. The idea of superman separates the thought of humanity into two sharply divided and very definite categories:

- Conception of man without the idea of superman; scientific (positivist) conception of man, and also a considerable part of philosophical conception of man.

- Conception of man from the point of view of the idea of superman; mystical, occult, and theosophical conception of man (though here it must be noted that almost everything that is known under these names is pseudo-mystical, pseudo-occult, and pseudo-theosophical conception).

In the first case man is taken as a completed being. Study is made of his anatomical structure, his physiological and psychological functions, his present position in the world, his historical fate, his culture and civilisation, the possibility of the better organisation of his life, his possibilities of knowledge, etc. In all this, man is taken as what he is. Attention is concentrated on the results of man's activities, his attainments, his discoveries, his inventions, and these results are regarded as proofs of his evolution — although, as so often happens, they demonstrate just the contrary.

The idea of evolution in this conception of man is taken as the general evolution of all men, of the whole of mankind. Mankind is regarded as evolving. Although such an evolution has nothing analogous to it in Nature and cannot be explained by any biological example, Western thought is in no way disconcerted by this and continues to speak of evolution.

In the second case, man is taken as an uncompleted being, out of which something different should result. In this case, the whole meaning of the existence of this being lies in its transition into this new state. Man is regarded as a grain, as a larva, as something temporary and subject to transformation. All that refers to man is taken from the point of view of this transformation; in other words, the value of everything in man's life is determined by whether or not it is useful for this transformation.

However, the idea of transformation itself remains very obscure. From the point of view of superman, the conception of man cannot be regarded as either popular or progressing. It enters as an indispensable attribute into semi-occult, semi-mystical teachings, but it plays no part in the scientific, or in the more widely spread pseudo-scientific, philosophies of life.

The reason for this is to be seen in the complete divergence of Western culture from religious thought. Were it not for this divergence, the conception of man from the point of view of the idea of superman would not be lost because religious thought, in its true sense, is impossible without the idea of superman.

The absence of the idea of superman from the majority of modern philosophies of life is to a considerable extent the cause of the terrible chaos of thought in which modern humanity lives. If men tried to connect the idea of superman with all the more or less accepted views, they would see that it shows everything in a new light, presenting from new angles the things which they thought they knew quite well, reminding them of the fact that man is only a temporary visitor, only a passenger, on the Earth.

Naturally, such a view could not be popular. Modern philosophies of life (or at least a great many of them) are built on sociology or on what is called sociology. Sociology never thinks of a time so remote that a new type will have developed out of man, but is concerned only with the present or the near and immediate future. It is precisely this attitude which serves to show the mere scholasticism of that science. Like any other scholastic science, sociology deals not with living facts but with artificial abstractions. Dealing with the "average level" and "the average man", sociology does not see the relief of the mountains, does not understand that neither humanity nor individual man is something flat and uniform.

Humanity, as well as individual man, is a mountain chain with high snow summits and deep ravines and is, moreover, in that unsettled geological period when everything is in process of formation — when whole mountain ranges vanish, when deserts appear in place of seas, when new volcanoes rise, when fields and forests are buried under the flow of boiling lava, when continents emerge and perish, and when glacial periods come and go. An "average man", with whom alone sociology can deal, does not exist in reality any more than the "average mountain" exists.

It is impossible to indicate when a new, a more stable, type is formed. It is being formed continuously. Growth proceeds without interruptions. There is never a moment when anything is accomplished. A new type of man is being formed now and amongst us. The selection goes on in all races and nations of the Earth except in the most backward and degenerating races. The latter include the races usually considered the most advanced, that is, those completely absorbed in pseudo-culture.

Superman does not belong to the historical future. If superman can exist on Earth, he must exist both in the past and in the present. But he does not stay in life: he appears and goes away.

Table of Contents

Just as in becoming a plant a grain of wheat goes out of the sphere of the life of grains, just as in becoming an oak an acorn goes out of the life of acorns, just as in becoming a chrysalis a caterpillar dies for caterpillars and in becoming a butterfly goes completely out of the sphere of observation of caterpillars, in the same way superman goes out of the sphere of observation of other people, goes out of their historical life.

An ordinary man cannot see a superman or know of his existence, just as a caterpillar cannot know of the existence of a butterfly. This is a fact which we find extremely difficult to admit, but it is natural and psychologically inevitable. The higher type cannot in any sense be controlled by the lower type or be the subject of observation by the lower type; but the lower type may be controlled by the higher and may be under the observation of the higher. From this point of view the whole of life and the whole of history can have a meaning and a purpose which we cannot comprehend.

This meaning, this purpose, is superman. All the rest exists for the sole purpose that out of the masses of humanity crawling in the Earth, superman should from time to time emerge and rise, and by this very fact go away from the masses and become inaccessible and invisible to them.

The ordinary view of life either finds no aim in life or sees the aim in the "evolution of the masses". But the evolution of the masses is as fantastic and illogical an idea as would be, for instance, the idea of the identical evolution of all the cells of a tree or any other organism. We do not realise that the idea of the evolution of the masses is equivalent to expecting all the cells of a tree, that is, the cells of the roots, bark, wood-fibre, and leaves to be transformed into flowers and fruit.

Evolution, which is usually regarded as evolution of the masses, can in reality never be anything but evolution of the few. In mankind, such an evolution can only be conscious. In man, only degeneration proceeds unconsciously.

Nature has in no way guaranteed a superman. She holds within herself all possibilities, including the most sinister. Man cannot be promoted to superman as a reward, either for a long term of service as a man, or for irreproachable conduct, or for his sufferings — whether accidental or unintentionally created for himself by his own stupidity or lack of adaptability to life, or even intentionally for the sake of the reward which he hopes to gain.

Nothing leads to superman except the understanding of the idea of superman, and it is precisely this understanding that is becoming ever rarer.

For all its inevitability, the idea of superman is not at all clear. The psychological outlines of superman elude modern man like a shadow. Men create superman according to their own likeness and image, endowing him with their qualities, tastes, and defects in an exaggerated form.

To superman are ascribed features and qualities which can never belong to him, features which are entirely contradictory and incompatible, which deprive one another of any value and ultimately destroy one another. The idea of superman is generally approached from the wrong angle; it is taken either too simply, merely on one plane, or too fantastically, without any connection with reality. The result is that the idea is distorted, and men's treatment of it becomes increasingly erroneous.

In order to find a right approach to this idea, we must first of all create for ourselves a harmonious picture of superman. Vagueness, indefiniteness, and diffuseness are in no way necessary attributes of the picture of superman. We can know more about him than we think, if only we want to and know how to set about it. We have perfectly clear and definite lines of thought for reasoning about superman and perfectly definite notions, some connected with the idea of superman and others opposed to it. All that is required is to avoid confusing them. Then the understanding of superman, the creation of a harmonious picture of superman, will cease to be such an unattainable dream as it sometimes appears.

The inner growth of man follows quite definite paths. It is necessary to determine and to understand these paths; otherwise, when the idea of superman is already accepted in one form or another, but is not connected vitally with the life of man, it takes strange, sometimes grotesque or monstrous, forms. People who think naively picture superman to themselves as a kind of exaggerated man in whom both the positive and negative sides of human nature have developed with equal freedom and have reached the utmost limits of their possible development. But this is exactly what is impossible. The most elementary acquaintance with psychology, certainly if we take psychology as real understanding of the laws of the inner being of man, shows that the development of features of one kind can only proceed at the expense of features of another kind. There are many contradictory qualities in man which we can in no case develop on parallel lines.

The imagination of primitive peoples pictured superman as a giant, a man of Herculean strength, extremely long-lived. We must revise the qualities of superman, i.e., the qualities ascribed to superman, and determine whether these qualities can be developed only in man. If qualities which can exist apart from man are attributed to superman, it becomes evident that these qualities are wrongly connected with him. The sought-for qualities must be such as can develop only in superman. For instance, gigantic size cannot by any means be a quality of absolute value for superman; modern biology knows very well that man cannot be taller than a certain height because his skeleton would not bear a weight that greatly surpassed that of man's body. Neither does enormous physical strength present an absolute value. Man can with his own weak hands construct machines more powerful than any giant. For "nature", for the "Earth", the strongest imaginable giant is only a pigmy, imperceptible on its surface. Neither is longevity, however great it may be, a sign of inner growth. Trees can exist for thousands of years. A stone can exist for hundreds of thousands of years.

These qualities are of no value in superman, because they can be manifested apart from him.

Qualities must develop in superman which cannot exist in a tree or in a stone, qualities with which neither high mountains nor earthquakes can compete.

Table of Contents

The development of the inner world, the evolution of consciousness, is an absolute value which can in the world known to us develop only in man and cannot develop apart from man.

The evolution of consciousness, the inner growth of man, is the "ascent towards superman". But inner growth proceeds on several lines simultaneously. These lines must be established and determined, because mingled with them are many deceptive false ways which lead man aside, turn him backward, or bring him into blind alleys.

It is of course impossible to dogmatise a form of the intellectual and emotional development of superman, but several sides of it can be shown with perfect exactitude.

Thus the first thing that can be said is that superman cannot be thought about on the ordinary "materialistic" plane. Superman must necessarily be connected with something mysterious, something of magic and sorcery.

Consequently, an interest directed towards the "mysterious" and the "inexplicable", a gravitation towards the "occult", are inevitably connected with evolution towards superman. Man suddenly feels that he cannot continue to ignore much that has hitherto seemed to him unworthy of attention. He begins to see everything as it were with new eyes, and all the "fairy-like", the "mystical", which yesterday he smilingly rejected as superstition, unexpectedly acquires for him some new deep meaning, either symbolical or real.

He finds new meanings in things, unexpected and strange analogies. An interest in the study of old and new religions appears in him. His thought penetrates the inward meaning of allegories and myths, and he finds a deep and strange significance in things which formerly looked self-evident and uninteresting.

It may be that interest in the mysterious and the miraculous creates the chief watchwords serving to unite men who begin to discover the hidden meaning of life. But the same interest in the mysterious and the miraculous also serves to test people. A man who has retained the possibilities of credulity or superstition will infallibly run on to one of the many rocks which lie submerged in the sea of occultism; he will succumb to the seduction of some mirage — will in one way or another lose his aim.

At the same time superman cannot be simply a "great businessman" or a "great conqueror" or a "great statesman" or a "great scientist". He must inevitably be either a magician or a saint. Russian heroic legends always ascribe to their heroes traits of magical wisdom, that is, of "secret knowledge".

But as has already been emphasised, the expectation of superman is too often connected with the usual theories of evolution, that is, with the idea of general evolution, and superman is regarded in this case as a possible product of the evolution of man. It is curious that this seemingly most logical theory destroys the idea of superman. The cause of this lies, of course, in the wrong view of evolution in general. Moreover, for some reason, superman cannot be regarded as a higher zoological type in comparison with man, as a product of the general law of evolution. There is in this view some radical mistake which is clearly felt in all attempts to form an image of the superman of the distant and unknown future. The picture appears too nebulous and diffuse; the image of superman in this case loses all colour and grows almost repulsive as though from the very fact of becoming lawful and inevitable. Superman must have something unlawful in him, something which violates the general course of things, something unexpected, unsubjected to any general laws.

This idea is expressed by Nietzsche:

I want to teach men the sense of their existence, which is the superman, the lightning out of the dark cloud — man. — F. Nietzsche: Thus Spake Zarathustra.

Nietzsche understood that superman cannot be regarded as the product of a historical development which can be realised in the distant future, or as a new zoological species. Lightning cannot be regarded as the result of the "evolution of the cloud".

But the feeling of the "unlawfulness" of superman, his "impossibility" from the ordinary point of view, causes people to attribute to him features that are really impossible, and so superman is often pictured as a kind of Juggernaut car, crushing people in its progress.

Malice, hatred, pride, conceit, selfishness, cruelty, are all considered superhuman on the sole condition that they reach the furthest possible limits and do not stop at any obstacle. Complete liberation from all moral restraint is considered superhuman or approaching superhuman. "Superman" in the vulgar and falsified sense of the word means: all is permitted.

The supposed a-morality of superman is associated with the name of Nietzsche. But Nietzsche is not guilty of this idea. On the contrary, perhaps no one has ever put into the philosophy of superman so much longing for true morality and for true love as Nietzsche. He was destroying only the old petrified morality which had long since become anti-moral. He rebelled against ready-made morality, against the invariable forms which in theory are obligatory always and for everyone, and in practice are violated always and by everyone.

Verily I have taken from you perhaps a hundred formulae and your virtue's favourite playthings; and now you upbraid me, as children upbraid.

They played by the sea — then there came a wave and swept their playthings into the deep; and now they cry.

And further:

When I came unto men, I found them resting on an old infatuation: all of them thought they had long known what was good or bad for men.

I disturbed this somnolence when I taught that no one yet knows what is good and bad — unless it be the creating one.

— F. Nietzsche: Thus Spake Zarathustra.

In Nietzsche the moral feeling is the feeling of artistic creation, the feeling of service.

Often it is a very stern and merciless feeling. Zarathustra says:

Oh, my brethren, am I then cruel? But I say, what falls, that shall I also push!

Obviously these words are doomed to misunderstanding and misinterpretation. The cruelty of Nietzsche's superman is regarded as his chief feature, as the principle underlying his treatment of men. The great majority of Nietzsche's critics do not wish to see that this cruelty of superman is turned against something inner, something in himself, against everything that is "human, all too human", small, vulgar, literal, and inert, which makes man the corpse which Zarathustra carried on his back.

The non-understanding of Nietzsche is one of the curious examples of a non-understanding which is almost intentional. Nietzsche's idea of superman is clear and simple. It is sufficient to take the beginning of Zarathustra:

Thou great star! What would be thy happiness if thou hadst not those for whom thou shinest?

For ten years hast thou come up hither to my cave; thou wouldst have satiated of thy light and of thy journey had it not been for me, my eagle and my serpent.

But we awaited thee every morning, took thy superfluity from thee, and blest thee for it.

Lo! I am satiated with my wisdom, like the bee that has gathered too much honey; I need hands held out for it.

I would fain bestow and distribute...

Therefore I must descend into the deep, as thou dost in the evening....

Bless the cup, then, that is about to overflow, that the water may flow golden out of it, and carry everywhere the reflection of thy bliss.

And further:

Zarathustra went alone down the mountain and no one met with him. When, however, he entered the forest, there suddenly stood before him an old man.... And thus spake the old man to Zarathustra.

No stranger to me is this wanderer. Many years ago passed he by. Zarathustra was he called, but he has altered.

Then thou carriedst thine ashes into the mountains; wilt thou now carry thy fire into the valleys? Fearest thou not the incendiary's doom?

Yea, I recognised Zarathustra. Pure is his eye, and no loathing lurketh about his mouth....

Zarathustra answered:

I love men.

And after this, Nietzsche's ideas were regarded as one of the causes of German militarism and chauvinism!

All this lack of understanding of Nietzsche is curious and characteristic because it can be compared only with the lack of understanding on the part of Nietzsche himself of the ideas of Christianity and of the Gospels. Nietzsche understood Christ according to Renan . Christianity was for him the religion of the weak and the miserable. He rebelled against Christianity, opposed superman to Christ, and did not wish to see that he was fighting the very thing that had created him and his ideas.

[Nietzsche did not or would not understand that his superman was to a considerable extent the product of Christian thought. Moreover, Nietzsche was not generally very frank, even with himself, regarding the sources of his inspirations. I have never found, either in his biographies or in his letters, any indication of his acquaintance with contemporary "occult" literature. At the same time he obviously knew it well and made use of it.

It is very interesting to draw a parallel between some passages in the chapter on "The Bestowing Virtue" in Nietzsche's Zarathustra and chapter IX, Vol. I, in the Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magic of Eliphas Lévi. — PDO]

The fundamental feature of superman is power. The idea of "power" is very often connected with the idea of demonism, and then appears the demoniacal man.

Table of Contents

Many people have been enthusiastic about demonism, but nevertheless the idea is utterly false and is in its essence not of a very high order. As a matter of fact the "beautiful demonism" we know is one of the "pseudo-ideas" by which people live. We do not know and do not want to know the real demonism, such as must be accorded to a right meaning of the idea. All evil is very small and very vulgar. There can be no strong and great evil. Evil always consists in the transforming of something great into something small. But how can people reconcile themselves to such an idea? They must necessarily have "great evil".

Evil is one of the ideas which exist in the minds of men in a falsified form, in the form of their own "pseudo-images". Our whole life is surrounded by such pseudo-images. We have a pseudo-Christ, a pseudo-religion, a pseudo-civilisation, pseudo-sciences, etc.

But generally speaking there can be two kinds of falsification: the first, and more usual, is where a substitute is given in place of the real thing — "instead of bread, a stone, and instead of fish, a serpent" ; the second, a little more complex, is where "base truth" is transformed into an "exalting lie" . This occurs when an idea or a phenomenon, constant and common in our life, and small and insignificant in its nature, is painted over and decorated with such zeal that at last people begin to see in it a certain disturbing beauty and some features which invite imitation.

A very beautiful "Sad demon, spirit of exile" is created precisely through such a falsification of the clear and simple idea of the "devil".

Lermontoff's "demon" or Milton's "Satan" is a pseudo-devil. The idea of the devil (the slanderer), the spirit of evil and lies, is intelligible and necessary in the dualistic philosophy of the world. But then the devil has no attractive features, whereas the "demon" or "Satan" possesses many beautiful and positive qualities: power, intelligence, contempt of everything small and vulgar. None of these is a feature of the devil.

The demon or Satan is an embellished, falsified devil. The real devil is, on the contrary, the falsification of everything brilliant and strong; he is counterfeit, plagiarism, vilification, vulgarisation, the "street", the "gutter".

In his book on Dostoevsky, A L Volinsky drew particular attention to the way in which Dostoevsky depicted the devil in The Brothers Karamazoff.

The Devil whom Ivan Karamazoff sees is a parasite in check trousers who suffers from rheumatism and has lately had himself vaccinated against smallpox.

The devil is vulgarity and triviality embodied. Everything he says is mean and vile; it is scandal, filthy insinuation, the desire to play upon the most repulsive sides of human nature. The whole sordidness of life spoke with Ivan Karamazoff in the person of the devil. We are, however, inclined to forget the real nature of the devil and are more willing to believe the poets who embellish him and make him into an operatic demon. The same demoniacal traits are ascribed to superman. But it is enough to look at them more closely to see that they are nothing more than pure falsification and deceit, taking us very far from the fundamental idea and leading us into a blind alley.

Speaking generally, in order to understand the idea of superman it is useful to have in mind everything opposed to the idea. From this point of view it is interesting to note that besides a devil in check trousers who has had himself vaccinated, there is another very well-known type uniting in itself all in man that is most opposed to the superman.

Table of Contents

Such is Pontius Pilate, the Roman procurator of Judea in the time of Jesus.

The rôle of Pilate in the Gospel tragedy is extremely characteristic and significant, and if it was a conscious rôle, it would be one of the most difficult. But it is strange that of all the rôles in the Gospel drama, the rôle of Pilate needs least of all to be a conscious one. Pilate could not "make a mistake", could not act in this way or that way, and therefore he was taken in his natural state as a part of the surroundings and conditions, just as were the people who gathered in Jerusalem for the Passover and the crowd who shouted "Crucify him!".

The rôle of Pilate is identical with the rôles of the other "Pilates" in life in general. It is not sufficient to say that Pilate tried Jesus, wanted to free him, and finally executed him. This does not determine the essence of his nature. The chief point lies in the fact that Pilate was almost the only one who understood Jesus. He understood him, of course, in his own Roman way; yet in spite of understanding Jesus he delivered him to be scourged and executed. Pilate was undoubtedly a very clever man, well educated and cultured. He saw very clearly that the man who stood before him was no criminal "preaching sedition to the people" or "inducing them not to pay the taxes", etc., as was declared to him by the "truly Jewish people" of that time; that this man was not a pretender, not an impostor who called himself the King of Judea, but simply a "philosopher", as he could define Jesus to himself.

This "philosopher" aroused his sympathy, even his compassion. The Jews clamouring for the blood of an innocent man were repellent to him. He tried to help Jesus. But it was too much for him to fight for Jesus and incur unpleasantness: so, after a short hesitation, Pilate delivered him up to the Jews.

It was probably in Pilate's mind that he was serving Rome and in this particular case was safeguarding the peace of its rulers, maintaining order and quiet among the subject people, averting the cause of possible unrest, even to the extent of sacrificing an innocent man for it. It was done in the name of politics, in the name of Rome, and the responsibility seemed to fall on Rome. Certainly Pilate could not have known that the days of Rome itself were already numbered, and that he himself was creating one of the forces that were to destroy Rome. But the thinking of Pilates never goes so far as that. Moreover, with regard to his own actions, Pilate had a very convenient philosophy: everything is relative, everything is a question of point of view, nothing is of any particular value. It was a practical application of the "principle of relativity". On the whole, Pilate is a very modern man. With such a philosophy it is easy to find the way amidst the difficulties of life.

Jesus even helped him. He said:

"For this cause came I into the world that I should bear witness to the truth."

Pilate answered, ironically: "What is truth?"

This at once put Pilate into his accustomed way of thinking and acting, reminded him who and where he was, showed him how he should look at things.

Pilate's essential feature is that he sees the truth but does not wish to follow it. In order to avoid following the truth which he sees, he has to create for himself a special sceptical and mocking attitude towards the very idea of truth and towards the adherents of the idea. In his own heart he is no longer able to regard them as criminals; he has outgrown this; but he must cultivate in himself a certain slightly ironical attitude towards them which will allow him to sacrifice them when necessary.

Pilate went so far that he even tried to set Jesus free, but of course he would not have allowed himself to do anything that could compromise him. This would have made him ridiculous in his own eyes. When his attempts failed, as he probably could foresee, he came out to the people and washed his hands, showing by this that he disclaimed all responsibility.

The whole of Pilate is in this. The symbolical washing of hands is indissolubly connected with the image of Pilate. The whole of him is in this gesture.

For a man of real inner development there cannot be any washing of hands. This gesture of inner deceit can never belong to such a man.

"Pilate" is a type expressing that which in cultured humanity hinders the inner development of man and forms the chief obstacle on the way to superman. Life is full of big and small Pilates. The crucifixion of Christ can never be accomplished without their help. They see and understand the truth perfectly. But any "regrettable necessity", or interests of politics as understood by them, or interests of their own position, may force them to betray truth and then to wash their hands.

In relation to the evolution of the spirit, Pilate is a stop. Real growth consists in the harmonious development of mind, feeling, and will. A one-sided development, that is, in this instance, the development of mind and will without the corresponding development of feeling, cannot go far. In order to betray truth, Pilate had to make truth itself relative. This relativity of truth adopted by Pilate helps him to find a way out of the difficult situations in which his own understanding of the truth places him. At the same time this very relativity of truth stops his inner development, the growth of his ideas. One cannot go far with relative truth. "Pilate" is bound to find himself in a closed circle.

Table of Contents

Another remarkable type in the Gospel drama, a type also opposed to everything which in ordinary humanity leads to the superman, is Judas.

Judas is a very strange figure in the Gospel tragedy. There is no one about whom so much has been written as Judas. In modern European literature there are attempts to represent and interpret Judas from all possible points of view. Contrary to the usual "Church" interpretation of Judas as a mean and greedy "Jew" who sold Christ for thirty pieces of silver, he is sometimes represented as a figure higher even than Christ, as a man who sacrificed himself, his salvation, and his "life eternal" in order that the miracle of redemption should be accomplished; or as a man who revolted against Christ because Christ, in his opinion, spoiled "the cause", surrounded himself with worthless people, put himself in a ridiculous position, and so on.

Actually, however, Judas is not even a "rôle", and certainly not a romantic hero, not a conspirator desirous of strengthening the union of the apostles with the blood of Christ, not a man struggling for the purity of the idea. Judas is simply a small man who found himself in the wrong place, an ordinary man full of distrust, of fears and suspicions, a man who ought not have been among the disciples, who understood nothing of what Jesus said to his disciples, but a man who for some reason or other was accepted as one of them and was even given a responsible position and a certain authority. Judas was considered one of the favourite disciples of Jesus; he was in charge of the apostles' domestic arrangements, was their treasurer. Judas' tragedy was that he feared to be exposed; he felt himself in the wrong place and dreaded the thought that Jesus might one day reveal this to others. At last he could bear it no longer. He did not understand some words of Jesus; perhaps he felt a threat in these words, perhaps a hint at something which only he and Jesus knew. Perturbed and frightened, Judas fled from the supper of Jesus and his disciples and decided to expose Jesus. The famous thirty pieces of silver played no part in this. Judas acted under the influence of injury and fear; he wished to break and destroy that which he could not comprehend, that which revolted and humiliated him by the very fact of its being above his understanding. He needed to accuse Jesus and his disciples of crimes in order to feel himself in the right. Judas' psychology is a most human psychology, the psychology of slandering what one does not understand.

Table of Contents

The placing of Pilate and Judas side by side with Jesus is a wonderful feature of the Gospel drama; it would be impossible to find or imagine a more striking contrast. If the Gospels were to be regarded simply as a literary work, a work of art, then the placing together of Christ, Pilate, and Judas would point to the hand of a great author. In short scenes, in a few words, there are shown here contradictions which not only have not disappeared in the human race in two thousand years, but have grown and developed with great luxuriance.

Instead of approaching inner unity, man recedes farther and farther from it, but the question of attaining this unity is the most essential question of the inner development of man. Unless he attains inner unity, man can have no "I", can have no will. The concept of "will" in relation to a man who has not attained inner unity is entirely artificial.

Most of our actions are prompted by involuntary motives. The whole of life is composed of small things which we continually obey and serve. Our "I" continually changes as in a kaleidoscope. Every external event which strikes us, every emotion suddenly aroused, becomes caliph for an hour, begins to build and govern, and is in its turn as unexpectedly deposed and replaced by something else. The inner consciousness, without attempting to disperse the illusory designs created by the shaking of the kaleidoscope and without understanding that in reality the power that decides and acts is not itself, endorses everything and says about those moments of life in which different external forces are at work, "This is I, this is I".

From this point of view "the will" can be defined only as the "resultant of desires". Consequently, so long as desires have not become permanent, man is the plaything of moods and external impressions. He never knows what he will say or do next. Not only the next day, but even the next moment, is hidden from him by the wall of accident.

What appears to be the consecutiveness of men's actions finds its explanation in the poverty of motives and desires, or in the artificial discipline grafted by "education", or, above all, in men's imitation of one another. As to the men with a so-called "strong will", these are usually men of one dominating desire in which all other desires vanish.

Table of Contents

If we do not understand the absence of unity in the inner world of man, we do not understand the necessity of such a unity in superman, just as we do not understand many of his other features. Thus superman appears to us a dried-up being, rational and deprived of emotions, whereas in reality the emotionality of superman, that is, his ability to feel, must far exceed ordinary human emotionality.

The psychology of superman eludes us because we do not understand the fact that the normal psychic state of superman constitutes what we call ecstasy in all possible meanings of this word.

Ecstasy is so far superior to all other experiences possible to man that we have neither words nor means for the description of it. Men who have experienced ecstasy have often attempted to communicate to others what they have experienced, and these descriptions, often coming from different centuries, from people who have never heard of one another, are wonderfully alike and contain above all similar cognitional aspects of the Unknown. Moreover, the descriptions of real ecstasy contain a certain inner truth which cannot be mistaken and the absence of which is felt at once in cases of sham ecstasy as it occurs in descriptions of the experiences of the "saints" of the formal religions.

Speaking in general, a description in plain words of the experience of ecstasy presents almost insurmountable difficulties. Only art, that is, poetry, music, painting, architecture, can succeed in transmitting, though in a very feeble way, the real content of ecstasy. All true art is in fact nothing but an attempt to transmit the sensation of ecstasy. Only the man who finds in it this taste of ecstasy will understand and feel art.

If we define "ecstasy" as the highest degree of emotional experience — which is probably a perfectly correct definition — it will become clear to us that the development of man towards superman cannot consist in the growth of the intellect alone. Emotional life must also evolve, in certain not easily comprehensible forms. The chief change in man must come from the evolution of emotional life.

If we imagine man approaching the new type, we must understand that he will have a certain peculiar life of his own which will be very little like the lives of ordinary men and difficult for us to conceive. There will be very much suffering in his life — there will be sufferings which as yet affect us but very little and there will also be joys of which ordinary men have no idea, and even a feeble reflection of which reaches us only rarely.

Table of Contents

But for the man who undergoes no change through contact with the idea of superman there is in this idea a certain feature which imparts to it a very gloomy aspect. This is the remoteness of the idea, the fact that superman is very far away, cut off from us, from ordinary life. We occupy one place in life; he occupies a quite different place, having no relation to us except that in some way we create him. When people begin to realise their relation to superman from this point of view, a certain vague doubt begins to creep in and gradually develops into a more definite and very unpleasant feeling which is shaped into a quite definitely negative view of the whole idea.

People may reason, and often have reasoned, in this way: Let us grant that superman will come and that he will be exactly as we have pictured him, a new and enlightened being, and that he will be in a sense the result of the whole of our life. But what is it to us if it is he who will exist and not we? What are we in relation to him? Soil, on which will grow a gorgeous flower? Clay, out of which will be modelled a beautiful statue? We are promised a light which we shall never see. Why should we serve the light which will shine for others? We are beggars, we are in the dark and the cold, and we are comforted by being shown the lights of a rich man's house. We are hungry and we are told of the magnificent feast in which we can have no part. We spend our whole life in collecting pitiful crumbs of knowledge, and then we are told that all our knowledge is illusion; that in the soul of a superman a light will spring forth in which he will see in a flash all that we have so eagerly sought, aspired to, and could never find.

The misgivings which assail people when they encounter the idea of superman have a very sound basis. They cannot be passed by. They cannot be disposed of by saying that man must find happiness in being conscious of his connection with the idea of superman. These are nothing but words, "man must"! And what if he does not feel happiness? Man has a right to know, has a right to ask questions; why must he serve the idea of superman, why must he submit to this idea, why must he do anything?

In order to find the true meaning of the idea of superman it is necessary to understand that the idea is much more difficult than is generally thought. This is so because, for its right expression and understanding, the idea requires new words, new concepts, and a knowledge which man may not always possess. All that is set forth here, all that portrays superman, even if it introduces something new into the understanding of the idea, is far from being sufficient. Ideas such as that of superman cannot be considered on the level of ordinary ideas relating to things and phenomena of the three-dimensional world. The idea of superman recedes into infinity and, like all ideas that recede into infinity, it requires a very particular approach — that is, from the direction of infinity.

In the ancient Mysteries there existed a consecutive and graduated order of initiation. In order to be raised to the next degree, to ascend the next step, the man to be initiated had to pass through a certain definite course of preparation. He was then subjected to the required tests, and only after he had passed through all the tests and proved that his preparation had been serious and on the right lines were the next doors opened before him and he penetrated more deeply into the interior of the temple of initiation.

Table of Contents

One of the first things that the candidate for initiation learned and had to appreciate was the impossibility of following a path of his own choice and the danger which awaited him if he failed to remember all that he had to remember. He was told of the awful consequences following a violation of the order of initiation, the terrible punishments which awaited the man to be initiated who dared to enter the sanctuary without having observed all these rules. The first requirement was to realise the necessity of advancing by steps. He had to realise that it was impossible for him to out-distance himself, and that any attempt in this direction was certain to end tragically. A rigorous consecutiveness of inner development was the fundamental rule of the Mysteries. If we try to analyse psychologically the idea of initiation, we shall understand that initiation was an introduction into a circle of new ideas. Each further degree of initiation represented the disclosing of a new idea, a new point of view, a new angle of vision. In the Mysteries, new ideas were not disclosed to a man until he had proved himself sufficiently prepared to receive them.

In this order of initiation into new ideas a deep understanding of the properties of the world of ideas can be seen. The ancients understood that reception of each new idea required special preparation; they understood that an idea caught in passing can easily be seen in a wrong light, or received in a wrong way, and that a wrongly received idea can produce very undesirable and even disastrous results.

The Mysteries and the gradual initiations were to protect people from the half-knowledge which is often much worse than no knowledge at all, particularly in questions of the Eternal, with which the Mysteries had to deal.

The same system of gradual preparation of people for the reception of new ideas is brought forward in all the rituals of magic.

The literature on magic and occultism was for a long time entirely ignored by Western scientific and philosophical thought or rejected as an absurdity and a superstition. It is only quite recently that people began to understand that all these teachings must be taken in a symbolical way, as a complex and subtle picture of psychological and cosmic relations.

A strict and unswerving observance of various small rules, which often look trivial, incomprehensible, and unrelated to anything important, is demanded by all the rituals of ceremonial magic. Again, the horrors which await the man who has broken the order of the ceremonies, or changed it of himself, or omitted something by neglect, are described. There are many legends of magicians who invoked a spirit but lacked the power to control it. This happened either because the magician forgot the words of the invocation, or in some way broke the magic ritual, or because he invoked a spirit stronger than himself, stronger than all his invocations and magic figures.

All these instances of the men who break the ritual of initiation in the Mysteries, or of the magicians who invoke spirits stronger than themselves, equally represent in allegorical form the position of a man in relation to new ideas which are too strong for him to handle because he has not the required preparation. The same idea was expressed in the legends and tales of the sacred fire which consumed the uninitiated who incautiously approached it, and in the myths of gods, of goddesses the sight of whom was not permitted to mortals on pain of death. The light of certain ideas is too strong for man's eyes, especially when he sees it for the first time. Moses could not look at the burning bush; on Mount Sinai he could not look upon the face of God. All these allegories express one and the same thought, that of the terrible power and danger of new ideas which appear unexpectedly.

The Sphinx with its riddle expressed the same idea. It devoured those who approached it but could not solve the riddle. The allegory of the Sphinx means that there are questions of a certain order which man must not approach unless he knows how to answer them.

The idea of superman is closely connected with the problem of time and eternity, with the Riddle of the Sphinx. In this lie its attraction and its danger; this is why it so strongly affects the souls of men.

As was pointed out earlier, modern psychology does not realise the immense danger of certain themes, ideas, and questions. Even in primitive philosophy, when men divided ideas into divine and human, they understood better the existence of different orders of ideas. Modern thought does not recognise this at all. Existing psychology and the theory of knowledge do not teach people to discriminate between different orders of ideas, nor point out that some ideas are very dangerous and cannot be approached without long and complicated preparation. This occurs because modern psychology generally does not take into consideration the reality of ideas, does not understand this reality. To a modern mind ideas are an abstraction from facts; in our eyes ideas have no existence of themselves. That is why we get so badly burned when we touch certain ideas. For us "facts", which do not exist, are real; and ideas, which alone exist, are unreal.

Ancient and medieval psychology understood better the position of the human mind in relation to ideas. It understood that the mind could not deal with ideas in a right way so long as the reality of them was not clear to it. Further, the old psychology understood that the mind was incapable of receiving ideas of different kinds simultaneously or out of the right order, that is, it could not without preparation pass from ideas of one order to ideas of another order. It understood the danger of such irregular and disorderly dealing with ideas. The question is, in what must the preparation consist? Of what do the allegories of the Mysteries and magic rituals speak?

First of all they speak of the necessity of an adequate knowledge for every order of ideas, because there are things which cannot be approached without preliminary knowledge.

In other domains we understand this perfectly. It is impossible without adequate knowledge to operate a complicated machine such as an aircraft.

A man is shown an electric machine. Its parts are explained, and he is told: "If you touch these parts, you will die". Everybody understands this and realises that in order to know the machine it is necessary to learn a great deal and to learn for a long time. Everybody realises also that machines of different kinds require different knowledge, and that by having learned to work a machine of one kind one does not become able to operate all kinds of machines.

An idea is a machine of enormous power.

But this is exactly what modern thought does not realise.

Every idea is a complicated and delicate machine. In order to know how to handle it, it is necessary first to possess a great deal of purely theoretical knowledge and, besides that, a large amount of experience and practical training. Unskilled handling of an idea may produce an explosion of the idea; a fire begins, the idea burns and consumes everything around it.

From the point of view of modern understanding, the whole danger is confined to wrong reasoning, and there it ends. In reality, however, this is far from being the end of the matter. One error in reasoning leads to a whole series of others. Certain ideas are so powerful, contain so much hidden energy, that either a right or a wrong deduction from them will inevitably produce enormous results. There are ideas which reach the most hidden recesses of the soul of man and which, once they have affected it, leave an everlasting trace. Moreover, if the idea is taken wrongly, it leaves a wrong trace, leading a man astray and poisoning his life.

A wrongly received idea of superman acts precisely in this way. It detaches man from life, sows deep discord in his soul and, giving him nothing, deprives him of what he had.

It is not the fault of the idea itself, but of a wrong approach to it.

Table of Contents

In what, then, must a right approach consist?

As the idea of superman has points of contact with the problem of time and with the idea of the infinite, it is not possible to touch the idea of superman without having cleared up the means of approach to the problem of time and to the idea of the infinite.

Without knowing these laws a man will not know what effort will be produced by his touching the machine, by his pulling one lever or another.

The problem of time is the greatest riddle humanity has ever had to face. Religious revelation, philosophical thought, scientific investigation, and occult knowledge all converge at one point, that is, on the problem of time — and all come to the same view of it.

Time does not exist! There exist no perpetual and eternal appearance and disappearance of phenomena, no ceaselessly flowing fountain of ever appearing and ever vanishing events. Everything exists always! There is only one eternal present, the Eternal Now, which the weak and limited human mind can neither grasp not conceive.

But the idea of the Eternal Now is not at all the idea of a cold and merciless predetermination of everything, of an exact and infallible pre-existence. It would be quite wrong to say that if everything already exists, if the remote future exists now, if our actions, thoughts, and feelings have existed for tens, hundreds, and thousands of years and will continue to exist for ever, it means there is no life, no movement, no growth, no evolution.

People say and think this because they do not understand the infinite and want to measure the immeasurable depths of eternity with their weak and limited finite minds. Of course they are bound to arrive at the most hopeless of all possible solutions of the problem. Everything is, nothing can change, everything exists beforehand and eternally. Everything is dead and immovable in frozen forms amidst which beats our consciousness, which has created for itself the illusion of the movement of everything around it, a movement which in reality does not exist.

But even such a weak and relative understanding of the idea of infinity as is possible for the limited human intellect, provided only that it develops along the right lines, suffices to destroy "this gloomy phantom of hopeless immobility".

The world is a world of infinite possibilities.

Our mind follows the development of possibilities always in one direction only. But in fact every moment contains a very large number of possibilities, all of which are actualised — only we do not see it and do not know it. We always see only one of the actualisations, and in this lies the poverty and limitation of the human mind. If we try to imagine the actualisation of all the possibilities of the present moment, then of the next moment, and so on, we shall feel the world growing infinitely, incessantly multiplying by itself and becoming immeasurably rich and utterly unlike the flat and limited world we have pictured to ourselves up to this moment. Having imagined this infinite variety we shall feel a "taste" of infinity for a moment and shall understand how inadequate and impossible it is to approach the problem of time with earthly measures. We shall understand what an infinite richness of time going in all directions is necessary for the actualisation of all the possibilities that arise each moment. We shall understand that the very idea of arising and disappearing possibilities is created by the human mind, because otherwise it would burst and perish from a single contact with the infinite actualisation. Simultaneously with this we shall feel the unreality of all our pessimistic deductions as compared with the vastness of the unfolding horizons. We shall feel that the world is so boundlessly large that a thought of the existence of any limits in it, a thought of there being anything whatever which is not contained within it, will appear to us ridiculous.

Where, then, are we to seek for a true understanding of "time" and "infinity"? Where to seek for this infinite extension in all directions from every moment? What ways lead to it? What ways lead to the future which exists now? Where to find the right methods of dealing with it? Where to find the right methods of dealing with the idea of superman? These are questions to which modern thought gives no answer.

But human thought has not always been so helpless in the face of these problems. There have existed, and there still exist, other attempts to solve the riddles of life.

The idea of superman belongs to the "inner circle". Ancient religions and myths always pictured in the image of superman the higher "I" of man, man's consciousness. This higher "I", or higher consciousness, was always represented as a being almost separate from ordinary man but, in a certain sense, living within man.

It depended on man himself whether he drew nearer to this being, became it, turned aside from it, or even broke away from it altogether.

The image of superman as a being belonging to the remote future or to the Golden Age or to the mythical present very often symbolised this inner being, the higher "I", the superman in the past, the present, and the future.

What was symbol and what was reality depended on the way of thinking of the particular man in question. People who were inclined to regard the outer as objectively existing considered the inner to be a symbol of the outer. People who understood differently and knew that the outer did not mean the objective, considered outer facts to be symbols of the possibilities of the inner world.

Table of Contents

But in reality the idea of superman has never existed apart from the idea of higher consciousness.

The ancient world was never superficially materialistic. It always knew how to penetrate the depths of an idea and how to find in it not only one meaning but many. The world of today, having made the idea of superman concrete in one sense, has deprived it of its inner power and freshness. Superman as a new zoological species is above all tedious. He is possible and admissible only as "higher consciousness".

What is higher consciousness?

Here, it is necessary to note that any division into "higher" and "lower" as, for instance, of higher and lower mathematics, is always artificial. In reality, of course, the lower is nothing but a limited conception of the whole, and the higher is a broader and less limited conception. In relation to consciousness this question of "higher" and "lower" stands thus: the lower consciousness is a limited self-consciousness of the whole, while the higher consciousness is a fuller consciousness.

You have made your way from worm to man, and much is still in you of the worm. Once were ye apes, and even yet in man more of an ape than any of the apes. — Nietzsche: Thus Spake Zarathustra.

Of course these words of Zarathustra have nothing to do with the "theory of Darwin". Nietzsche spoke of the discord in the soul of man, of the struggle between the past and the future. He understood the tragedy of man, which lies in the fact that in his soul there live simultaneously a worm, an ape, and a man.

In what relation, then, does such an understanding of the idea of superman stand to the problem of time and to the idea of the infinite? Where to seek for "time" and for "infinity"?

The ancient teachings again answer: in the soul of man. Everything is within man, and there is nothing outside him.

How is this to be understood?

Time is not a condition of the existence of the Universe, but only a condition of the perception of the world by our psychic apparatus, which imposes on the world conditions of time, since otherwise the psychic apparatus would be unable to conceive it.

Western thought, at least the evolving part of it, the part that builds no dogmatic barriers for itself, also finds "further possibilities of studying problems of time in passing to questions of psychology" (Minkovsky).

The "passing to questions of psychology" in problems of space and time, of the necessity for which Minkovsky speaks, would mean for natural science the acceptance of Kant's proposition that time and space are nothing but forms of our sense perception and originate in our psychic apparatus.

We are, however, unable to conceive infinity without relation to space and time. Therefore, if space and time are forms of our perception and lie in our soul, it follows that the roots of infinity are also to be sought within us, within our soul. We may perhaps define it as an infinite possibility of the expansion of our consciousness.

The depths hidden within the consciousness of man were well understood by philosopher-mystics whose thought was closely connected with parallel systems of Hermetic philosophy, alchemy, Cabala, and others.

"Man contains within himself heaven and hell", they said; and their representations of man often showed him with the different faces of God and the worlds of "light and darkness" in him. They affirmed that by penetrating within the depths of himself man can find everything, attain everything. What he will attain depends on what he seeks and how he seeks — and they did not understand this as an allegory. The soul of man actually appeared to them as a window or as several windows looking on infinity. Man in ordinary life appeared to them as living, so to speak, on the surface of himself, ignorant and even unconscious of what lies in his own depths.

If he thinks of infinity he conceives it as outside him. In reality infinity is within him. By consciously penetrating within the soul, man can find infinity within himself, can come into contact with it and enter into it.

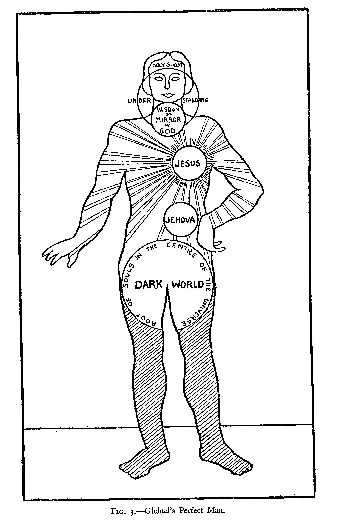

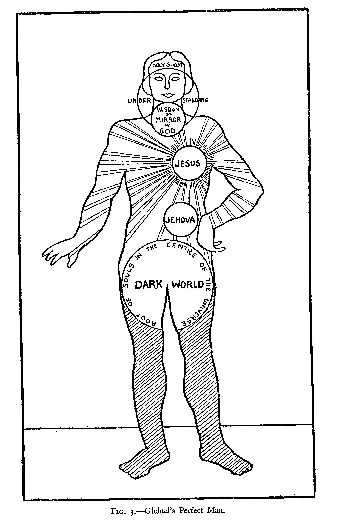

Gichtel, a mystic of the 17th century, gives a drawing of the "perfect man" in his remarkable book Theosophia Practica.

The perfect man is the cabalistic Adam Kadmon, i.e., humanity or mankind, of which an individual man is a copy.

The drawing represents the figure of a man on whose head (on the forehead) is shown the Holy Ghost; in the heart, Jesus; in the "solar plexus", Jehovah. The upper part of his chest with the organs of respiration (and possibly the organs of speech) contains the "Wisdom" or the "Mirror of God", and the lower part of the body with its organs contains the "Dark World" or the "Root of Souls in the Centre of the Universe".

The drawing represents the figure of a man on whose head (on the forehead) is shown the Holy Ghost; in the heart, Jesus; in the "solar plexus", Jehovah. The upper part of his chest with the organs of respiration (and possibly the organs of speech) contains the "Wisdom" or the "Mirror of God", and the lower part of the body with its organs contains the "Dark World" or the "Root of Souls in the Centre of the Universe".

Thus this drawing represents in man five ways into infinity. Man can choose any of these ways; and what he will find will depend on his direction, that is, on which way he takes.

Gichtel says:

Man has become so earthly and outward that he seeks afar, beyond the starry sky, in the higher eternity, what is quite near him, within the inner centre of his soul.

When the soul begins to strive to divert its will from the exterior constellation and abandon everything visible in order to turn to God, to its Centre, this requires desperate work.

The more the soul penetrates within itself, the nearer it approaches God until it finally stops before the Holy Trinity. Then it has reached deep knowledge.

— J G Gichtel: Theosophia Practica (1696), Traduite en francais. Paris, 1897 (Bibliothèque Rosicricienne), Introduction, p. 14.

Such an inward understanding of the idea of infinity is much truer and deeper than the outward understanding of it, and it gives a more correct approach to the idea of superman, a clearer understanding of it. If infinity lies in the soul of man and if he is able to come into contact with it by penetrating within himself, this means that the "future" and "superman" are in his soul, and that he can find them in the right way.

The peculiarity and distinctive feature of the idea of the "real" world, i.e., the world as it is, are that, viewed in a "positivist" light, they appear absurd. This is a necessary condition. But this condition and the necessity for it are never properly understood, and that is why the ideas of the "world of many dimensions" often produces such a nightmare effect on people.

Superman is one of the possibilities which lie within the depths of the soul of man. It rests with man himself to bring this idea nearer or to turn it aside. The nearness or remoteness of superman from man lies not in time, but in an active and practical relation to it. Man is separated from superman not by time but by the fact that he is not prepared to receive superman. The whole of time lies within man himself. Time is the inner obstacle to a direct sensation of one thing or another, and it is nothing else. The building of the future, the serving of the future, are but symbols of man's attitude towards himself, towards his own present. It is clear that if this view is accepted and if it is recognised that all the future is contained within man himself, it will be naïve to ask: what have I to do with superman? It is evident that man has to do with superman, for superman is man himself.

Table of Contents

Yet the view of superman as the higher "I" of man, as something within himself, does not contain all possible understanding.