Contents List:Notre Dame de ParisEgypt and the Pyramids The Sphinx The Buddha with the Sapphire Eyes The Soul of the Empress Mumtaz-I-Mahal The Mevlevi Dervishes |

Return to:Title Page |

A small medieval town surrounded by fields, vineyards, and woods. A growing Paris which several times outgrows its walls. The Paris of the last centuries, "which changes its face very fifty years", as Victor Hugo remarked. And the people ... for ever going somewhere past these towers, for ever hurrying somewhere and always remaining where they were, seeing nothing, noticing nothing, always the same people. And the towers, always the same, with the same gargoyles looking on at this town, which is for ever changing, for ever disappearing and yet always remaining the same.

Here two lines in the life of humanity are clearly seen. One is the line of the life of these people below; the other, the line of the life of those who built Notre Dame. Looking down from these towers you feel that the real history of humanity, the history worth speaking of, is the history of the people who built Notre Dame and not that of those below, and you understand that these are two quite different histories.

One history passes by in full view and, strictly speaking, is the history of crime, for if there were no crimes there would be no history. All the most important turning-points and stages of this history are marked by crimes: murders, acts of violence, robberies, wars, rebellions, massacres, tortures, executions. Fathers murdering children, children murdering fathers, brothers murdering one another, husbands murdering wives, wives murdering husbands, kings massacring subjects, subjects assassinating kings.

This is one history which everybody knows, the history which is taught in schools.

The other history is the history which is known to very few. For the majority, it is not seen at all behind the history of crime. But what is created by this hidden history exists long afterwards, sometimes for many centuries, as does Notre Dame. The visible history, the history proceeding on the surface, the history of crime, attributes to itself what the hidden history has created. But actually, the visible history is always deceived by what the hidden history has created.

So much has been written about the Cathedral of Notre Dame, and so little is actually known about it. One who has never tried to find out anything about it for himself, or to make something out of the available material, would never believe how little is in fact known about the building of the cathedral. It took many years to build; the dates when it was begun and when it was finished are known; the bishops who, in one way or another, contributed to this construction are also known, and so are the popes and kings of that time. But nothing has remained concerning the builders themselves with the exception of names, and even that seldom. "In the voluminous records of the church of Notre Dame, which go back beyond the 12th century, there is not a single word about the actual work of the construction of the cathedral. According to the chronicles of the period before the Gothic, the libraries of monasteries were full of descriptions of the construction of their buildings and of the biographies and praises of their builders. But with the coming of the Gothic period, suddenly all became silent. Until the 12th century there is no mention of any of the architects." [From a book by Viollet-le-Duc. PDO] No facts have remained concerning the schools which stood behind all that was created by that strange period which began about the year one thousand and lasted for about four centuries.

It is known that there existed schools of builders. Of course they had to exist, for every master worked, and ordinarily lived, with his pupils. In this way painters, sculptors, and architects naturally worked. But behind these individual schools stood other institutions of very complex origin. There were not merely architectural schools or schools of masons. The building of cathedrals was part of a colossal and cleverly devised plan which permitted the existence of entirely free philosophical and psychological schools in the rude, absurd, cruel, superstitious, bigoted and scholastic Middle Ages. These schools have left us an immense heritage, almost all of which we have already wasted without understanding its meaning and value.

These schools, which built the "Gothic" cathedrals, concealed themselves so well that traces of them can now be found only by those who already know that such schools must have existed. Certainly the Catholic Church of the 11th and 12th centuries, which already used the torture and stake for heretics and strangled all free thought, did not build Notre Dame. There is not the slightest doubt that for a time the Church was made an instrument for the preservation and propagation of the ideas of true Christianity that is, of true religion or true knowledge which were absolutely foreign to it.

There is nothing improbable in the fact that the whole scheme of the building of cathedrals and of the organisation of schools under cover of this building activity was created because of the growing "heretic-mania" in the Catholic Church and because the Church was rapidly losing those qualities which had made it a refuge for knowledge.

By the end of the first thousand years of the Christian era the monasteries had gathered all the science, all the knowledge, of that time. But the legalisation of the hunting and persecution of heretics, and the approach of the Inquisition, made it impossible for knowledge to reside in monasteries.

There was then found or, to speak more accurately, created for this knowledge a new and convenient refuge. The knowledge left the monasteries and passed into architectural schools, "schools of masons". The style later called "Gothic", and at this time known as the "new" or "modern", of which the characteristic feature was the pointed arch, was accepted as the distinctive sign of the schools. The schools within presented a complex organisation and were divided into different degrees. This means that in every "school of masons" where all the sciences were taught, there were inner schools in which the true meaning of religious allegories and symbols were explained and in which was studied "esoteric philosophy" or the science of the relations between God, man, and the Universe. In other words, these schools taught the very "magic" for a mere thought of which people were put on the rack and burnt at the stake. The schools lasted up to the Renaissance, when the existence of "secular science" became possible. The new science, carried away by the novelty of free thought and free investigation, very soon forgot its origin and beginning, and forgot also the rτle of the "Gothic" cathedrals in the preservation and successive transmission of knowledge.

But Notre Dame has remained, and to this day guards and shows us the ideas of the schools and the ideas of the true "freemasons".

It is known that Notre Dame, at least in its exterior, is at present nearer to what it was originally than it has been during the past three centuries. After an incalculable number of ignorant pious alterations, after the storm of revolution which had destroyed what had survived these alterations, Notre Dame was restored in the second part of the 19th century by a man who had deep understanding of its idea. But what has remained of the really old and what is new is difficult to say, not for the lack of historical data but because the "new" is often in fact the "old".

Such, for instance, is the tall, slender, pierced spire over the eastern part of the cathedral, from which the twelve Apostles, preceded by the apocalyptic beasts, are descending to the four corners of the world. The old spire was demolished in 1787. What we now see is a structure of the 19th century and, together with the figures of the Apostles, is the work of Viollet-le-Duc, the restorer of the cathedral during the Second Empire.

But not even Viollet-le-Duc could create the view from the big towers over the city including this spire and the Apostles; he could not create the whole scenic effect which was undoubtedly a part of the builders' design. The spire with the Apostles is an inseparable part of this view. You stand on top of one of the big towers and look towards the east. The city, the houses, the river, the bridges, the tiny microscopic people, not one of whom sees the spire or the Teachers descending upon Earth preceded by the apocalyptic beasts. This is quite natural, because from there, from the Earth, it is difficult to distinguish them. If you go there, to the embankment of the Seine, to the bridge, the Apostles will appear from there almost as small as the people appear from here, and they will merge into the details of the roof of the cathedral. They can be seen only if one knows of their existence. But who cares to know?

What about the gargoyles? They are regarded either simply as ornament or as individual creations of different artists at different times. In actual fact, however, they are among the most important features of the builders' design.

This design is very complex. To be more exact, it is not even one design, but several designs completing one another. The builders wished to put all their knowledge, all their ideas, into Notre Dame. You find there mathematics, astronomy, and some very strange ideas of biology or "evolution" in the stone bushes on which human heads grow, on the balustrade of the large platform under the flying buttresses.

The gargoyles and other figures of Notre Dame transmit to us the psychological ideas of its builders, chiefly the idea of the complexity of the soul. These figures are the soul of Notre Dame, its different "I"s: pensive, melancholy, watching, derisive, malignant, absorbed in themselves, devouring something, looking intensely into a distance invisible to us, as does the strange woman in the head-dress of a nun, which can be seen above the capitals of the columns of a small turret high up on the south side of the cathedral.

The gargoyles and all the other figures of Notre Dame possess one very strange property: beside them people cannot be drawn, painted, or photographed; beside them, people appear dead, expressionless, stone images.

It is difficult to explain these "I"s of Notre Dame; they must be felt, and they can be felt. But it is necessary to choose the time when Paris becomes quiet. This happens before daybreak, when it is not yet light but when it is already possible to distinguish some of the strange beings sleeping above.

I remember such a night; it was before the war. I was making a short stay in Paris on the way to India and was wandering about the town for the last time. It was already growing light, and the air was becoming cold. The moon moved swiftly among the clouds. I walked round the whole cathedral. The huge massive towers stood as though on the alert. But I already understood their secret, and I knew that I was taking with me a firm conviction which nothing could shake: that this exists, that is, that there is another history apart from the history of crime, and that there is another thought which created Notre Dame and its figures. I was going to search for other traces of this thought, and I was sure that I should find them.

Eight years passed before I saw Notre Dame again. These were years of almost unprecedented commotion and destruction. It seemed to me that something had changed in Notre Dame, as though it was beginning to have a presentiment of its approaching end. During these years, which have written such brilliant pages into the history of crime, bombs dropped over Notre Dame, shells burst, and it was only by accident that Notre Dame did not share the fate of that wonderful fairy-tale of the twelfth century, Rheims Cathedral, which perished a victim of progress and civilisation.

When I went up the tower and again saw the descending Apostles, I was struck by the vainness and almost complete uselessness of attempts to teach people something they have no desire whatever to know.

Again, as many times before, I could find only one argument against this that perhaps the aim both of the teaching of the Apostles and of the construction of Notre Dame was not to teach all the people, but only to transmit certain ideas to a few men through the "space of time". Modern science conquers space within the limits of the surface of the small Earth. Esoteric science has conquered time, and it knows methods of transferring its ideas intact and of establishing communications between schools through hundreds and thousands of years.

1922.

On the bridge across the Nile I was filled with a strange and almost frightening sense of expectation. Something was changing around me. In the air, in the colours, in the lines, there was a magic which I did not yet understand.

Arab and Egyptian Cairo quickly disappeared; in its place, in everything that surrounded me, I felt Egypt, which enveloped me.

I felt Egypt in the air blowing softly from the Nile, in the large boats with their triangular sails, in the groups of palms, in the wonderful rose tints of the rocks of Mokattam, in the silhouettes of the camels moving on the road in the distance, in the figures of women in their long black cloaks with bundles of reeds on their heads.

This Egypt was felt as extraordinarily real, as though I was suddenly transferred into another world which, to my own astonishment, I seemed to know very well. At the same time I was aware that this other world was the distant past. But here it ceased to be past, appeared in everything, surrounded me, became the present. This was a very strange sensation and strangely definite.

The sensation surprised me all the more because Egypt had never attracted me particularly; books and Egyptian antiquities in museums made it appear not very interesting and even tedious. But here I suddenly felt something extraordinarily alluring in it and, above all, something close and familiar.

Later, when I analysed my impressions, I was able to find certain explanations for them, but at first they only astonished me, and I arrived at the pyramids strangely agitated by all that I had encountered on the way.

The pyramids appeared in the distance as soon as we crossed the bridge; then they were hidden behind gardens and again appeared before us and grew larger and larger.

When approaching them one sees that the pyramids do not stand on the level of the plain which stretches between them and Cairo, but on a high rocky plateau rising sharply from it.

The plateau is reached by a winding ascending road which goes through a cutting in the rock. Having walked to the end of this road you find yourself on a level with the pyramids, before the co-called Pyramid of Cheops, on the same side as the entrance into it. To the right in the distance is the second pyramid, and behind it, the third.

Here, having ascended to the pyramids, you are in a different world, not in the world you were in ten minutes ago. There fields, foliage, palms, were still about you. Here it is a different country, a different landscape, a kingdom of sand and stone. This is the desert. The transition is sharp and unexpected.

The sensation which I had experienced on the way came over me with renewed force. The incomprehensible past became the present and felt quite close to me, as if I could stretch out my arm into it, and our present disappeared and became strange, alien, and distant.

I walked towards the first pyramid. On a close view you see that it is built of huge blocks of stone, each more than half the height of a man. At about the level of a three-storied house there is a triangular opening the entrance into the pyramid.

From the very beginning, as soon as I had got up to the plateau where the pyramids stand, had seen them close, and had inhaled the air which surrounds them, I felt that they were alive. I had no need to analyse my thoughts on this subject. I felt it as real and unquestionable truth. I understood at the same time why all these people who were to be seen near the pyramids took them merely as dead stones. It was because all the people were themselves dead. Anyone who is at all alive cannot but feel that the pyramids are alive.

I now understood this and many other things.

The pyramids are just like ourselves, with the same thoughts and feelings, only they are very, very old, and know much. So they stand there and think and turn over their memories. How many thousands of years have passed over them? They alone know.

They are far older than historical science supposes.

All is quiet around them. Neither tourists, nor guides, not the British military camp visible not far off, disturb their calm and that impression of extraordinarily concentrated stillness which surrounds them. People disappear near the pyramids. The pyramids are grander and occupy more room than we imagine. The Great Pyramid is nearly three quarters of a mile round its base and the second only a little less. People are unnoticeable beside them. If you go as far as the third pyramid you are swallowed up in the real desert.

The first time I went there I passed a whole day by the pyramids and early the following morning went there again. During the two or three weeks I spent that time at Cairo, I went there almost every day.

I realised that I was attracted and held by sensations which I had never experienced before anywhere. Usually I sat on the sand between the second and third pyramids and tried to stop the flow of my thoughts, and at times it seemed to me that I heard the thoughts of the pyramids.

I did not examine anything as people do; I only wandered from place to place and drank in the general impression of the desert and of this strange corner of the Earth where the pyramids stand.

Everything here was familiar to me. Sun, wind, sand, stones, together made one whole from which I found it hard to go away. It became quite clear to me that I should not be able to leave Egypt as easily as I had left every other place. There was something here that I had to find, something that I had to understand.

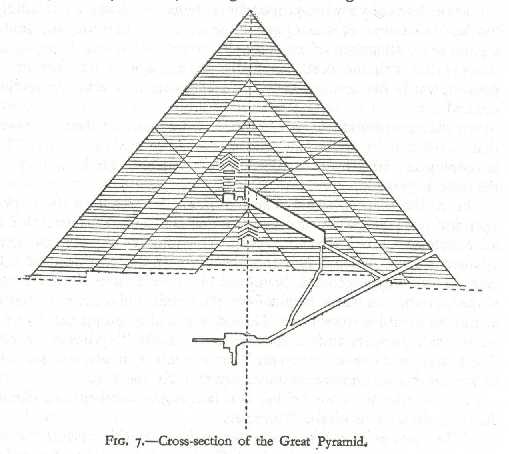

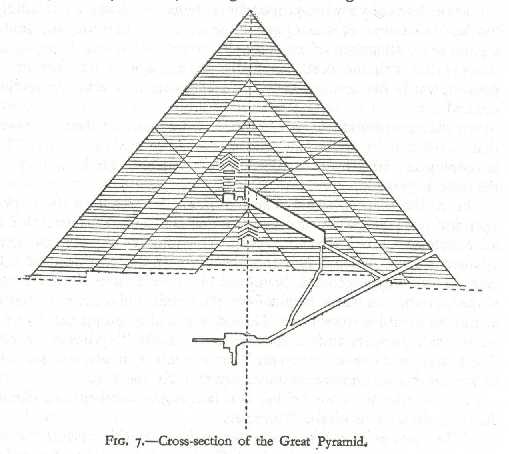

The entrance into the Great Pyramid is on the north side and rather high from the ground. The opening is in the form of a triangle. From it there leads a narrow passage which at once begins to descend at a steep angle. The floor is very slippery; there are no steps, but on the polished stone there are horizontal notches, worn smooth, into which it is possible to put one's feet sideways. Moreover, the floor is covered with fine sand and it is very difficult to keep oneself from sliding the whole way down. The Bedouin guide clambers down in front. In one hand he holds a lighted candle; the other he stretches out to you. You go down this sloping wall in a bent attitude. You at once become very hot from the effort and the unaccustomed attitude. The descent seems rather long at last it ends. You now find yourself in the place where a massive granite block once shut off the entrance, that is to say, approximately on the level of the base of the pyramid. From here it is possible to continue the descent to the "lower chamber", which is at a considerable depth below the level of the rock and it is also possible to climb up to the so-called "Chambers" of the King and Queen, which are approximately at the centre of the pyramid. In order to do this it is necessary first of all to get round the granite block of which I have spoken.

Some time, long ago according to one account at the time of the last Pharaohs, and according to others in the times of the Arabs the conquerors who tried to penetrate to the interior of the pyramid where there were supposed to be untold treasures, were stopped by this granite block. They could neither move nor pierce the block, and so they made a passage round it in the softer stone from which the pyramid was built.

The guide holds up his candle. You are now standing in a fairly large cavern and in front of you there is an obstacle which you must overcome in order to go further. This obstacle is something in the nature of a frozen or petrified waterfall by which you have to ascend. Two Arabs scramble up and reach their hands down to you. You climb up and, pressing yourself against the "waterfall", make your way sideways along a narrow ledge round the middle part of the frozen stone cascade. Your feet slip and there is nothing to hold by. At last you are there. Now it is necessary to ascend a little further, and before you appears the narrow black entrance of another corridor. It leads upwards. Holding on to the walls, breathing the stifling air with difficulty and drenched with sweat, you slowly make your way forward. The candles of the guides before and behind you feebly light the uneven stone walls. Your back begins to ache from the bent position. To all this is added a feeling of weight hanging over you, like that felt beneath the earth in the deep galleries of mines and pits.

At last you come out again into a place where you can stand upright. After a short rest you look round and in the feeble light of the candles you make out that you are standing before the entrance to a narrow, straight corridor, along which you can go without bending. This corridor leads straight to the "Chamber of the Queen".

To your right, if you stand facing the entrance to the corridor, you see the irregular black opening of a well, also made by treasure-seekers, and communicating with the lower subterranean chamber.

At the level of your head, over the entrance to the corridor leading to the "Chamber of the Queen", another corridor begins leading to the "Chamber of the King". This second corridor is not parallel to the first, but forms an angle with it; that is, it goes upwards like a steep staircase which begins a little above the ground.

In the construction of this upper corridor-staircase there is much that is difficult to understand and that at once strikes the eye. In examining it I very soon understood that this corridor is the key to the whole pyramid.

From the place where I stood, it could be seen that the upper corridor was very high, and along its sides, like the banisters of a staircase, were broad stone parapets descending to the ground, that is, to the level where I stood. The floor of the corridor did not reach down to the ground, being cut short, as I have already mentioned, at about a man's height from the floor. In order to get into the upper corridor from where I stood, one had to go up first by one of the side parapets and then drop down to the "staircase" itself. I call this corridor a "staircase" only because it ascends steeply. It has no steps, only worn-down notches for the feet.

Feeling that the floor behind you falls away, you begin to climb, holding on to one of the "parapets".

What strikes you first is that everything in this corridor is of very exact and fine workmanship. The lines are straight, the angles are correct. At the same time there is no doubt that this corridor was not made for walking along. Then for what was it made?

The answer to this is given by the "parapets". When you turn your attention to them, you see on them mathematically correct notched divisions at strictly equal distances from one another. These divisions are so precise that they immediately attract your attention. There is some idea, some intention, in them. Suddenly it becomes clear to you that up and down this "corridor" some kind of stone or metal plate, or "carriage", must have moved, which possibly, in its turn, served as a support for some measuring apparatus and could be fixed in any position. The divisions on the parapet show clearly that they were used for some kind of measurement, for finding certain angles.

No doubt remained in my mind that this corridor with its parapets was the most important place in the whole pyramid. It cannot be explained without the supposition of a "carriage" moving up and down the incline. This, in its turn, alters the whole conception of the pyramid and opens up entirely new possibilities.

At a definite time of the year the rays of certain stars can penetrate into the pyramid through the opening by which we entered it (until these stars become displaced in the progress of the great astronomical cycle). If we suppose that somewhere on the path of the rays mirrors are fixed, the rays penetrating through the opening of the pyramid will be thrown into the corridor on to the apparatus fixed on the movable carriage. There is no doubt that some kind of observations were carried out here, some data were established.

The granite block, round which goes what I called the stone waterfall, bars the way to these rays. But the meaning, the purpose, and the epoch of this block are completely unknown.

It is very difficult to define in our language the object and purpose of the pyramid. The pyramid was an observatory, but not only an "observatory" in the modern sense of the word, for it was also a "scientific instrument"; and not only an instrument or a collection of instruments, but also a "scientific treatise", or rather a whole library on physics, mathematics, and astronomy; or, to be still more exact, it was a "physico-mathematical faculty" and at the same time a "depository of measures", which is quite clearly shown by the measurements of the pyramid, the numerical interrelation of its height, base, sides, angles, and so on.

I has a very concrete feeling of the idea of the pyramid later, when I visited the famous observatory of Jay Singh at Jaipur, in Rajputana. This "observatory" is a huge square surrounded by walls, with strange buildings: stone triangles, the height of a large house; huge circles with divisions; empty cisterns resembling ponds with bridges across them and with polished brass bottoms for reflecting the stars; mysterious stone mazes which serve to find a definite constellation. All these are gigantic physical and astronomical apparati, gnomons, quadrants, sextants, and others that is, instruments which are now made of brass and kept in cases. If one imagines all these apparati and many others unknown to us combined into one, and supposes that their very measurements and the interrelation of their parts express the fundamental relations between the measurements of the different parts of, say, the solar system, the result will be the idea of the pyramid.

But I will continue the description of the pyramid as I saw it.

At the top, the inclined corridor with the parapets becomes horizontal and then leads into the "Chamber of the King". The two candles are insufficient to light the high smooth stone walls. It is rather stifling. By one wall there is something resembling a sarcophagus with high chipped sides.

I sent the guides away into the corridor and for some minutes remained alone.

I had a very strange feeling in this stone cell enclosed in the mass of the pyramid. The pulsation of life which filled the pyramid and emanated from it was felt here more strongly than anywhere. Besides this it appeared to me that this "Chamber" was telling me something about itself, but its words seemed to sound from behind a wall. I could hear but could not understand them. It seemed to me that it was necessary to make only quite a small effort and I should then hear everything. But I did not succeed in making this effort.

The "Chamber of the Queen" differs little from the "Chamber of the King", but for some reason does not give the same sensations. The lower subterranean chamber, which is more difficult to reach and is very stifling, is a little larger than the "King's Chamber" and is also full of thoughts and inaudible voices which are trying to impress something on you.

From the top of the pyramid my attention was attracted by the Dahshur Pyramid with irregular sides which is seen in the distance through field-glasses; the strange Step Pyramid situated nearer; and, not far from it, a large white pyramid.

A few days after my first visit to Gizeh I went to these distant pyramids. I did not want to see anything in particular, but wished to form a general impression of this part of the desert.

Having passed the Pyramid of Kheops and the Sphinx, I found myself on a broad road leading to Aboussir. As a matter of fact there was no road, but a broad track covered with traces of horses, donkeys, and camels. On the left, towards the Nile, lay ploughed fields. To the right there stretched a rocky cliff, beyond which the desert began.

From the very beginning of the road from Gizeh I began to experience this strange sensation of past as present which for some reason was produced in me by the Egyptian landscape. But this time I felt the desire to understand this sensation better, and I looked with particular intentness at everything around me, trying to decipher the secret of this magic of Egypt. I came to think that the secret might lie in the astonishing changelessness of the Egyptian landscape and its colours. In other countries nature changes its face several times a year. Even where for centuries the main features have been preserved, as in forests and steppes, the outer cover of nature, the grass, the leaves, all is new, just born. But here this sand and these stones are the same as those which had seen the people who built the pyramids, the Pharaohs and the Caliphs.

It seemed to me that in these stones which had seen so much, something of what they had seen was preserved, and that because of this a certain link was established through them with the life which existed in these places before and seemed still to be invisibly present here.

My grey Arab pony galloped quickly along by the uneven stone wall which lay on the right of the road, now nearer and now further off. I was more and more immersed in a strange feeling of liberation from everything by which we ordinarily live.

The whole present receded, appeared transparent like mist, and through it the past became more and more visible all around me, not taking any definite form but penetrating me by a thousand different sensations and emotions.

Nowhere had I ever before felt so clearly and definitely the unreality of the present. I felt here that all we consider as actually existing is nothing but a mirage which passes over the face of the Earth, perhaps the shadow or the reflection of some other life, or perhaps only dreams created in our imagination as a result of some obscure impacts and vague sounds which reach our consciousness from the Unknown which surrounds us.

I felt that everything vanished St Petersburg, London, Cairo, hotels, railways, steamers, people; everything became a mirage. But the desert around me existed, and I existed, though in a very strange way, without any connection with the present, but conscious of a very strong connection with the unknown past.

I felt there was in everything a not easily comprehensible but very subtle joy. I would describe it as the joy of liberation from oneself and the joy of feeling the incredible richness of life, which never dies but exists in an infinite variety of forms invisible and intangible for us.

Having passed Sakkara with the Step Pyramid and the white pyramid, I went further to the Dahshur pyramids. Here there was no road at all. The sand changed to small flints which formed what looked like enormous waves. When I came to level places and my pony began to gallop, it seemed to me several times that I was dropping money, for the flints flew up from the hoofs and tinkled like silver.

Even the first of the Dahshur pyramids produces an extraordinary and peculiar impression, as though it were sunk in its own thoughts but would presently notice you and would speak to you definitely and clearly. I rode slowly round it. There was not a soul near it, and nothing was visible but the sand and, in the distance, the pyramid with irregular sides.

I rode up to it. It is the strangest pyramid of all. I was only sorry that I could not be transported to this pyramid straight from Cairo, without seeing and feeling anything else. I was already too much saturated with impressions and could not fully appreciate what I felt here. But I felt that the stones here were animate and entrusted with a definite task. The south Dahshur Pyramid with the irregular lines of its sides struck me by its very definiteness, which was almost frightening.

At the same time I did not wish to formulate, even to myself, all that I felt. It was too much like imagination.

But my thoughts went on without obeying me and at times it appeared to me that I was really beginning to imagine things. But the sensation was quite different from that produced by imagination. There was something inexpressibly real in it. I turned my pony round and slowly rode back. Some distance off something seemed suddenly to push me. I quickly turned in the saddle. The pyramid was looking at me as though expecting something.

"Till next time", I said.

I could not fully analyse all the feelings that I had at that moment. But I felt that precisely here, if only I could remain here alone sufficiently long, my thoughts and sensations would reach such a degree of tension that I should really see and hear what is ordinarily invisible and inaudible. How far this was the result of the whole day and the whole week of unusual sensations, I could not say. But I felt that here my sensations of Egypt reached their highest intensity.

At the present time views on the pyramids can be divided into two categories. To the first category belongs the theory of tombs, and to the second, astronomical and mathematical theories.

Historical science, that is, Egyptology, keeps almost exclusively to the theory of tombs, with very small and feeble admissions in the direction of the possibility of the utilisation of pyramids for astronomical observations. Thus Professor Petrie in his book, A History of Egypt, speaks of three deep trnches which were cut in the rock and were about 160 feet long, 20 feet deep, and not over five or six feet wide. "The purpose of such trenches is quite unknown; but there may have been some system of observing azimuths of stars by a surface of water at the bottom, and a cord stretched from end to end at the top; by noting the moment of transit of the reflections of the star past the cord, an accurate observation of azimuth might be made".

But speaking generally, historical science is not interested in the astronomical and mathematical meaning of the pyramids.

If Egyptologists ever touch upon this side of the question, it is acting only as amateurs and so no great importance is attached to their opinions. R A Proctor's book, which I mention later, is an example of this.

The description of the construction of the pyramids (chiefly of the Great Pyramid) to be found in Herodotus is accepted as final and decisive.

Herodotus related what he was told about the construction of the Great Pyramid two or three thousand years before his time. He says that on the granite blocks covering the pyramid, hieroglyphic inscriptions were cut referring to various facts connected with its construction. Among other things there was recorded the amount of garlic, onions, and radishes that was eaten by the slaves who built the pyramid, and from the amount of garlic, etc., it was possible to draw conclusions as to the number of slaves and the duration of the work.

Herodotus says that before the Great Pyramid was built, a causeway had to be made through the desert on an embankment for the transport of the material. He himself saw this causeway which, according to his words, was a construction not less great than the pyramid itself.

The approximate date of the construction given by Herodotus is, owing to the profusion of small details pointed out by him, regarded in Egyptology as indisputable.

In reality all that Herodotus says is not in the least convincing. It must be remembered that Herodotus himself could not read hieroglyphs. This knowledge was carefully guarded and was the privilege of the priests. Herodotus could record only what was translated to him, and that certainly would have been only what confirmed and established the official version of the construction of the pyramids. This official version accepted in Egyptology may actually be far removed from the truth. The truth may be that what is regarded as the construction of the Great Pyramid was in reality its restoration. The pyramids may be much older than we think.

The Sphinx, which may have been constructed at the same times as the pyramids or still earlier, is quite rightly considered prehistoric. What does this mean? It means that some thousands of years before our era, possibly many thousands of years, the people or peoples who are known to us under the name of "ancient Egyptians" occupied the valley of the Nile and found, half buried in the sands, the pyramids and the Sphinx, the meaning and significance of which were quite incomprehensible to them. The Sphinx looked towards the East, so it was called the image of Harmakuti or the "Sun on the Horizon". Very much later the king to whom is ascribed the name of Kheops (Egyptologists have, or course, quite a different name for him) restored one of the pyramids and made it a mausoleum or sepulchre for himself. Moreover, the inscriptions cut into the facing of this pyramid described the doings of the king in a laudatory and exaggerated tone, and the restoration was of course called construction. These inscriptions misled Herodotus who took them for exact historical data.

The restoration of the pyramids was not their construction. The brother of Kheops, Khephren (the spelling and pronunciation of these names are very uncertain and unreliable) restored another pyramid. This gradually became a custom, and so it happened that some of the Pharaohs built for themselves pyramids, usually of smaller dimensions, and some restored the old, which were of larger dimensions. It is also possible that the first to be restored were the Dahshur Pyramids and the Step Pyramid at Sakkara. Gradually all the pyramids were converted into sepulchres, for a sepulchre was the most important thing in the life of the Egyptians of that period. But it was only an accidental episode in the history of the pyramids, and in no way explains their origin.

At the present time many interesting facts have been established concerning the Great Pyramid, but these discoveries belong either to astronomers or to mathematicians. If it happens that any Egyptologists speak of them, there are only very few who do so, and their opinions are usually suppressed by others.

In a way the reason for this is understandable, for too much charlatanism has accumulated around the study of the astronomical and mathematical significance of the pyramids. For instance, theories exist and books are published proving that the measurements of the various parts of corridors and walls inside the Great Pyramid represent the whole of history from Adam to "the end of general history". According to the author of one such book, prophecies contained in the pyramid refer chiefly to England and even give the length of the duration of post-war cabinets.

The existence of such "theories" of course makes it clear why science is afraid of new discoveries concerning the pyramids. But this in no way diminishes the value of existing attempts to establish the astronomical and mathematical meaning of the pyramids so far, in most cases, only the Great Pyramid.

R A Proctor in his book, The Great Pyramid (London, 1883), regards the pyramid as a kind of telescope or transit apparatus. He draws special attention to the slots in the parapets of the grand gallery and finds that they were made for moving up and down the incline whatever instruments were used for carrying out observations. Further, he points to the possible existence of a water-mirror at the junction of the ascending and descending passages and asserts that the pyramid was a clock for Egyptian priests and chiefly an astronomical clock.

Abbι Moreau in his book Les Enigmes de la Science has collected almost all the existing material relating to the Great Pyramid as a "depository of measures" or as a mathematical compendium. The sum of the sides of the base of the pyramid divided by its height gives the relation of the circumference to diameter, the number pi, which plays such an important rτle in the history of mathematics. The height of the pyramid is one millionth part of the distance of the Earth from the Sun (which, by the way, was established in science with sufficient accuracy only in the second half of the 19th century), etc., etc.

All this and many other things show the astounding narrowness of modern scientific views and the absence of even ordinary curiosity in the Egyptologists who come to a standstill at the theory of tombs and the story of Herodotus, and do not wish to know anything more. In reality the pyramids contain a great enigma. The pyramids, more than anything else in the world, tell us that we are quite wrong in considering that our ancestor was a "hairy, tailed quadruped, probably arboreal in its habits, and an inhabitant of the Old World". In actual fact our genealogy is much more interesting. Our ancestors were very rich and eminent people, and they left us an enormous inheritance which we have completely forgotten, especially since the time when we began to consider ourselves the descendants of a monkey.

1914-1925.

I used often to go to Gizeh from Cairo, sit down on the sand before the Sphinx, look at it and try to understand it, understand the idea of the artists who created it. On each and every occasion I experienced the same fear and terror of annihilation. I was swallowed up in its glance, a glance that spoke of mysteries beyond our power of comprehension.

The Sphinx lies on the Gizeh plateau where the great pyramids stand and where there are many other monuments, already discovered and still to be discovered, and a number of tombs of different epochs. The Sphinx lies in a hollow above the level of which only its head, neck, and part of its back project.

By whom, when, and why the Sphinx was erected of this nothing is known. Present-day archaeology takes the Sphinx to be prehistoric.

This means that even for the most ancient of the ancient Egyptians, those of the first dynasties six to seven thousand years before the birth of Christ, the Sphinx was the same riddle as it is for us today.

From the stone tablet inscribed with drawings and hieroglyphs found between the paws of the Sphinx, it was once surmised that the figure represented the image of the Egyptian god Harmakuti, "The Sun on the Horizon". But it has long been agreed that this is an altogether unsatisfactory interpretation and that the inscription probably refers to the occasion of some partial restoration made comparatively recently.

As a matter of fact the Sphinx is older than historical Egypt, older than her gods, older than the pyramids which, in their turn, are much older than is thought.

The Sphinx is indubitably one of the most remarkable, if not the most remarkable, of the world's works of art. I know nothing that it would be possible to put side by side with it. It belongs indeed to to quite another art than the art we know. Beings such as ourselves could not create a Sphinx. Nor can our culture create anything like it. The Sphinx appears unmistakably to be a relic of another, a very ancient culture, which was possessed of knowledge far greater than ours.

There is a tradition or theory that the Sphinx is a great, complex hieroglyph, or a book in stone, which contains the whole totality of ancient knowledge and reveals itself to the man who can read this strange cipher which is embodied in the forms, correlations, and measurements of the different parts of the Sphinx. This is the famous riddle of the Sphinx which from the most ancient times many wise men have attempted to solve.

Previously, when reading about the Sphinx, it had seemed to me that it would be necessary to approach it with the full equipment of a knowledge different from ours, with some new form of perception, some special kind of mathematics, and that without these aids it would be impossible to discover anything in it.

But when I saw the Sphinx for myself, I felt something in it that I had never read and never heard of and that at once placed it for me among the most enigmatic and at the same time fundamental problems of life and the world.

At the first glance, the face of the Sphinx strikes one with wonder. To begin with, it is quite a modern face. With the exception of the head-ornament, there is nothing of "ancient history" about it. For some reason, I had feared there would be. I had thought that the Sphinx would have a very "alien" face. But this is not the case. Its face is simple and understandable. It is only the way that it looks that is strange. The face is a good deal disfigured. But if you move away a little and look at the Sphinx for a long time, it is as if a kind of veil falls from its face, the triangles of the head-ornament behind the ears become invisible, and before you there emerges clearly a complete and undamaged face with eyes which look over you and beyond into the unknown distance.

I remember sitting on the sand in front of the Sphinx on the spot from which the second pyramid in the distance makes an exact triangle behind the Sphinx and trying to understand, to read its glance. At first I saw only that the Sphinx looked beyond me into the distance. But soon I began to have a kind of vague, then a growing, uneasiness. Another moment, and I felt that the Sphinx was not seeing me, and not only was it not seeing, it could not see me; and not because I was too small in comparison with it or too insignificant in comparison with the profundity of wisdom it contained and guarded. Not at all. That would have been natural and comprehensible. The sense of annihilation and the terror of vanishing came from feeling myself in some way too transient for the Sphinx to be able to notice me. I felt that not only did these fleeting moments or hours which I could pass before it not exist for it, but that if I could stay under its gaze from birth to death, the whole of my life would flash by so swiftly for it that it could not notice me. Its glance was fixed on something else. It was the glance of a being who thinks in centuries and millennia. I did not exist and could not exist for it. And I could not answer my own question do I exist for myself? Do I, indeed, exist in any sort of sense, in any sort of relation? In this thought, in this feeling, under this strange glance, there was an icy coldness. We are so accustomed to feel that we are, that we exist. Yet all at once, here, I felt that I did not exist, that there was no I, that I could not be so much as perceived.

The Sphinx before me looked into the distance, beyond me, and its face seemed to reflect something that it saw, something which I could neither see nor understand.

Eternity! The word flashed into my consciousness and went through me with a sort of cold shudder. All ideas about time, about things, about life, were becoming confused. I felt that in these moments in which I stood before the Sphinx, it lived through all the events and happenings of thousands of years and that, on the other hand, centuries passed for it like moments. How this could be I did not understand. But I felt that my consciousness grasped the shadow of the exalted fantasy or clairvoyance of the artists who had created the Sphinx. I touched the mystery but could neither define nor formulate it.

Only later, when all these impressions began to unite with those which I had formerly known and felt, the fringe of the curtain seemed to move, and I felt that I was beginning slowly, slowly, to understand.

The problem of Eternity, of which the face of the Sphinx speaks, takes us into the realm of the Impossible. Even the problem of Time is simple in comparison with the problem of Eternity.

Hints towards the solution of the problem of Eternity can be found in the various symbols and allegories of ancient religions and in some of the modern as well as the ancient philosophies.

The circle is the image of Eternity: a line going into space and returning to its starting-point. In symbolism, it is the snake biting its own tail. But where is the beginning of the closed circle? Our thought, caught in a circle, also cannot escape from it.

A heroic effort of imagination, a complete break with everything logically comprehensible, natural, and possible, is necessary in order to divine the secret of this circle and to find the point where the end unites with the beginning, where the head of the snake bites its own tail.

The idea of eternal recurrence, which for us is connected with the name of Pythagoras and in modern times with that of Nietzsche, is precisely such a sweep of the sword over the knot of the Gordian car.

Only in the idea of return, of endless repetition, can we understand and imagine Eternity. But it must be remembered that in this case we shall have no knot before us, but only its severed parts. And having understood the nature of the knot in this divided aspect, we shall afterwards have to unite these fragments again in thought and from them create a whole.

1908-1914.

I stayed at a hotel outside Colombo, on the seashore, and from there I made a number of excursions going south to Galle, to the Buddhist monasteries, north to the toy town of Kandy, where stands the holy Temple of the Tooth, its white stones covered with green moss and further, to the ruins of Anuradhapura, a city which long before the birth of Christ had a population of two millions, and was destroyed during the invasion of the Tamils at the beginning of our era. It has long been overrun and swallowed up by the green jungle through which now for nearly fifteen miles stretch streets and squares overgrown with grass and bushes, foundations and the half-demolished walls of houses, temples, monasteries, palaces, reservoirs and tanks, fragments of broken statues, gigantic dagobas, bell-shaped brick buildings, and so on.

On returning to my hotel after one of these excursions, I stayed indoors for a few days, trying to write down my impressions above all, my conversations with the Buddhist monks who had been explaining the teaching of Buddha. These conversations had left me with a strange feeling of dissatisfaction. I could not give up the thought that in Buddhism there were many things of which we were not able to come to any understanding and which I should define in the words "miraculous" or "magical" that is to say, precisely what they denied.

Buddhism appeared to me in two aspects simultaneously. On the one hand I saw it as a religion full of light, full of softness and warmth, of all religions the furthest removed from what may be called "paganism", a religion which even in its extreme church-forms never blessed the sword, never employed compulsion in any form whatever; a religion which one might embrace while remaining in one's former religion. All this on the one hand. On the other hand a strange philosophy which tries to deny that which constitutes the essence and principal content of every religion the idea of the miraculous.

I immediately felt the bright side of Buddhism on entering any Buddhist temple, especially in the southern part of Ceylon. Buddhist temples are little green nooks resembling the hermitages in Russian monasteries: a white stone enclosure and within it a few small white buildings and a little belfry. Everything is always very clean and there is much verdure, many shadows, sun-flecks, and flowers. A traditional dagoba, a broad bell-shaped building with a surmounting spire, stands over buried treasure or relics. Beneath the trees is a semi-circle of carved stone altars on which are flowers brought by pilgrims and, in the evening, the lights of oil-lamps; and the inevitable sacred Bo-tree which resembles the elm in appearance. Pervading all, a sense of quietude and serenity carries you away from the clamour and contradictions of life.

But as soon as you seek to come nearer to Buddhism, you immediately encounter a whole series of formal obstacles and evasions. "Concerning this we must not speak; about this Buddha has forbidden us even to think; this we have not at all, never have had and never can have." Buddhism teaches only how one can liberate oneself from suffering, and liberation from suffering is possible only by overcoming in oneself the desire for life, the desire for pleasure, all desires in general. In this is the beginning and end of Buddhism; there is no mysticism, no hidden knowledge, no idea about the miraculous, no future except the possibility of liberation from suffering and annihilation.

But as I heard all this, I was inwardly convinced that it was not so, and that in Buddhism there were many things to which perhaps I could not give a name, but which were definitely connected with the very name of Buddha, i.e., "The Enlightened One": that precisely the idea of "illumination" or "enlightenment" constituted the principal essence of Buddhism, and assuredly not the arid and materialistic theories of liberation from suffering.

This contradiction which I felt so strongly would not allow me to write; it prevented me from formulating my impressions even to myself; it made me dispute mentally with the Buddhists with whom I had talked; it made me contradict them, argue with them, wish to compel them to recognise and talk of something of which they did not wish to speak.

Consequently, my work went badly. For several days I tried to write in the morning, but seeing that nothing came of it, I used to go for a stroll along the sea-shore or take a train to the town.

Once, on a Sunday morning, when our usually half-empty and sleepy hotel was filled wih people from the town, I went out early. This time I did not go by the sea but along the road which led from the shore inland, through the green meadows, past clumps of trees and, now and again, one or two huts.

The path which I took led out on to the main road running south from Colombo. I remembered that somewhere about here must be a Buddhist temple to which I had not yet been, and I asked an old Singalese, who was selling green coconuts in a little stall by the roadside, where the temple was. Some other people came along and by their united efforts they somehow managed to understand what I wanted, and told me that the temple was on this road towards Colombo and that a small path on the right would lead to it.

After going some distance I at last found among the trees the path of which they had told me and which led to the temple. Soon I caught sight of the enclosure and gates. I was met by the gate-keeper, a very talkative Singalese with a thick beard and the inevitable comb in his hair. First he took me into the new shrine, where some modern and quite uninteresting statues of Buddha and his disciples stood in a row. Then we looked at the vihare, where the monks live and where there is a school for children and a hall for preaching; then the dagoba, on the spire of which is set a large moonstone which is shown to tourists and, so far as I could understand, was considered the most remarkable object in the whole temple; then a huge spreading and apparently very ancient Bo-tree, which by its age showed the antiquity of the temple. Under this tree there was deep shade into which obviously the sun never penetrated, for the stone altars which stood in it were covered with fine green moss.

There were some extraordinarily picturesque spots among the buildings and trees; and I remembered that I had seen photographs of them before.

Finally we went to look at the old shrine. It was undoubtedly a very ancient building long, one-storeyed, columned, with a verandah. As is always the case with these shrines, the walls inside were covered with bright painting representing various episodes from the life of Prince Gautama and from other incarnations of Buddha. In the second room, the guide told me, was a very ancient statue of Buddha with sapphire eyes. Statues of Buddha are either standing, sitting, or reclining. This was a reclining Buddha. When we entered the second room of the shrine, it was quite dark, as the light from the door through which we came could not reach in. I struck a match and saw behind a latticed glass frame running the whole length of the wall a huge statue lying on its side with one hand under its head, and the strange gaze of eyes which were not looking at me and yet appeared to see me.

The gate-keeper opened another door and in the faint light that penetrated to where I was standing the face of the Buddha appeared before me. It was a face about a yard in length, painted yellow, with strongly marked dark lines round the nostrils, mouth, and eyebrows and with great blue eyes.

"Those eyes are real sapphires", my guide told me. "Nobody knows when this statue was made; but it is certainly more than a thousand years old."

"Will not the frame open?" I asked the guide.

"It does not open", he replied. "It has not been opened for over sixty years."

He went on talking, but I was not listening. The gaze of those great blue eyes attracted me.

A second or two passed and I understood that I was in the presence of a miracle.

The guide quietly went out behind me and sat on the steps of the verandah, and I was left alone with the Buddha.

The face of the Buddha was quite alive; he was not looking at me and yet he saw me. At first I felt nothing but wonder. I had not expected, and could not have expected, anything like it. But very soon wonder and all the other feelings and thoughts disappeared in new and strange sensations. The Buddha saw me, saw in me that which I could not see in myself, all that was hidden in the most secret recesses of my soul. Under his gaze, which, as it were, passed me by, I began to see all this myself. Everything that was small, superfluous, uneasy, and troubled came to the surface and displayed itself under this glance. The face of the Buddha was quite calm, but not expressionless, and full of deep thought and feeling. He was lying here deep in thought, and I had come, opened the doors, and stood before him, and now he was involuntarily judging me. But there was no blame or reproach in his glance. His look was extraordinarily serious, calm, and full of understanding. But when I attempted to ask myself what the face of the Buddha expressed, I realised that there could be no answer. His face was neither cold nor indifferent. On the other hand it would be quite wrong to say that it expressed warmth, sympathy, or compassion. All this would be too small to ascribe to him. At the same time it would also be wrong to say that the face of the Buddha expressed unearthly grandeur or divine wisdom. No, it was a human face, yet at the same time a face which men do not happen to have. I felt that all the words I could command would be wrong if applied to the expression of this face. I can only say that here was understanding.

Simultaneously I began to feel the strange effect which the Buddha's face produced in me. All the gloom that rose from the depths of my soul seemed to clear up. It was as if the Buddha's face communicated its calm to me. Everything that up to now had troubled me and appeared so serious and important now became so small, insignificant, and unworthy of notice that I only wondered how it could ever have affected me. I felt that no matter how agitated, troubled, irritated, and torn with contradictory thoughts and feelings a man might be when he came here, he would go away calm, quiet, enlightened, understanding.

I remembered my work, remembered the conversations with the Buddhists, remembered how I had failed to make clear to myself certain things relating to Buddhism. And I nearly laughed: so utterly useless had it all been. All Buddhism was in this face, in this gaze. Suddenly I seemed to understand certain things Buddha had forbidden men to speak of, things above human reason and above human words. Was it not right? Here I saw this face and felt it, and yet I was not able to say what it expressed. If nevertheless I tried to put it into words, that would be even worse because it would be a lie. In this perhaps lay the explanation of Buddha's prohibition. And Buddha had said also that he had imparted the whole of the teaching, and that no secret doctrine existed. Might this not mean that the secret was hidden not in secret words but in words known by all, but not understood by men? Was it not possible that this Buddha was the solution to the mystery, the key to it? The whole statue was here before me, there was nothing secret or hidden in it; but even so, could I say that I saw it? Would others see it and understand it even to the extent that I did? Why was it unknown? It must be that people fail to notice it, just as they fail to see the truth hidden in Buddha's words about liberation from suffering.

I looked at those deep blue eyes and felt that though my thoughts were near the truth they were not yet the truth, because the truth is richer and more varied than anything that can possibly be expressed in thoughts or words. At the same time I felt that this face really contained the whole of Buddhism. No books are necessary, no philosophical discourse everything is in Buddha's glance. One need only come here and be moved by this glance.

I went out of the shrine with the intention of returning on the following day and trying to photograph the Buddha. But for this purpose it would be necessary to open the frame. The gate-keeper to whom I spoke about the frame told me again that it could not be opened. However, I left with the hope of managing it somehow on the following day.

On the way back to the hotel I wondered how it could have happened that this Buddha was so little known. I was quite sure that it was not mentioned in any of the books on Ceylon which I had. And so it proved. In Cave's large Book of Ceylon there was actually a picture of this temple the inner court with the little stone stairway leading to the belfry and the old shrine in which the Buddha is, and even with the same gate-keeper who took me round; but not one word about the statue. This seemed all the more strange because, apart from the mystical significance of this Buddha and its value as a work of art, it was certainly one of the largest Buddhas I had seen in Ceylon and, moreover, had sapphire eyes. How it had been overlooked or forgotten I could not imagine. The cause is of course to be found in the intensely "barbarian" character of the Western crowd which penetrates into the East, and in its deep contempt for all that does not serve the immediate purposes of profit or entertainment. At some time or other the Buddha was probably seen and described by somebody, but afterwards it was forgotten. The Singalese certainly know of the Buddha with the Sapphire Eyes, but for them it just exists, in the same way that the sea or the mountains exist.

Next day I went again to the temple.

I went fearing that on this occasion I should neither see not feel what I had experienced the day before, that the Buddha with the Sapphire Eyes would suddenly prove to be just an ordinary stone statue with a painted face. But my fears were not confirmed. The Buddha's gaze was exactly the same, penetrating my soul, illuminating everything in it and, as it were, putting everything in order.

A day or two later I was in the temple again, and the gate-keeper now met me as an old acquaintance. Again the face of the Buddha communicated something to me that I could neither understand nor express. I intended to try and find out something about the history of the Buddha with the Sapphire Eyes, but it happened that almost immediately I had to leave for India. Then the war began, and the face of the Buddha remained far from me across the gulf of men's madness.

One thing is certain. This Buddha is quite an exceptional work of art. I do not know of any work in Christian art which stands on the same level as the Buddha with the Sapphire Eyes: that is to say, I know of no work which expresses in itself so completely the idea of Christianity as the face of the Buddha expresses the idea of Buddhism. To understand this face is to understand Buddhism.

There is no need to read large volumes on Buddhism or to talk with professors who study Eastern religions or with learned bhikshus. One must come here, stand before the Buddha, and let the gaze of those blue eyes penetrate one's soul, and one will understand what Buddhism is.

Often when I think of the Buddha I remember another face, the face of the Sphinx and the gaze of those eyes which do not see you. These are two quite different faces. Yet they have something in common: both of them speak of another life, of another consciousness, which is higher than man's consciousness. Therefore we have no words to describe them. When, by whom, or for what purpose these faces were created we do not know, but they speak to us of a real existence, of another life, and of the existence of men who know something of that life and can transmit it to us by the magic of art.

1914.

But everything that I had read, either then or before, left me with a kind of indefinite feeling as though all who had attempted to describe Agra and the Taj Mahal had missed what was most important.

Neither the romantic history of the Taj Mahal, nor the architectural beauty, the luxuriance and opulence of the decoration and ornaments, could explain for me the impression of the fairy-tale unreality of something beautiful but infinitely remote from life, the impression which was felt behind all the descriptions, but which nobody has been able to put into words or explain.

It seemed to me that here was a mystery. The Taj Mahal had a secret which was felt by everybody but which nobody could name.

Photographs told me nothing at all. A large and massive building, and four tapering minarets, one at each corner. In all this I saw no particular beauty, but rather something incomplete. The four minarets, standing separate like four candles at the corners of a table, looked strange and almost unpleasant.

In what, then, lies the strength of the impression made by the Taj Mahal? Whence comes the irresistible effect which it produces on all who see it? Neither the marble lace-work of the trellises, nor the delicate carving which covers its walls, nor the mosaic flowers, nor the fate of the beautiful Empress none of these could by itself produce such an impression. It must lie in something else. But in what? I tried not to think of it in order not to create a preconceived idea. But something fascinated me and agitated me. I could not be sure, but it seemed to me that the enigma of the Taj Mahal was connected with the mystery of death, that is, with the mystery regarding which, according to the expression of one of the Upanishads, "even the gods have doubted formerly".

The creation of the Taj Mahal dates back to the time of the conquest of India by the Mohammedans. The grandson of Akbar, Shah Jahan, was one of the conquerors who changed the very face of India. Soldier and statesman, Shah Jahan was at the same time a judge of art and philosophy; his court at Agra attracted all the most eminent scholars and artists of Persia, which was at that time the centre of culture for the whole of Western Asia.

However, Shah Jehan passed most of his life on campaign and in fighting. On all his campaigns he was invariably accompanied by his favourite wife, the beautiful Arjumand Banu or, as she was also called, Mumtaz-i-Mahal "The Treasure of the Palace". Arjuman Banu was Shah Jehan's constant adviser in all matters of subtle and intricate Oriental diplomacy, and she also shared his interest in the philosophy to which the invincible Emperor devoted all his leisure.

During one of these campaigns the Empress died, and before her death she asked Shah Jehan to build for her a tomb "the most beautiful in the world".

The Shah decided to build for the interment of the dead Empress an immense mausoleum on the bank of the river Jumna in Agra, his capital, and later to throw a silver bridge across the Jumna and on the other bank to build a mausoleum of black marble for himself.

Only half his plan was destined to be realised for when, twenty years later, the building of the empress' mausoleum was being completed, a rebellion was raised against the Shah by his son Aurangzeb, who later destroyed Benares. Aurangzeb accused his father of having spent on the building of the mausoleum the whole revenue of the state for the last twenty years. Having taken his father captive, Aurangzeb shut him up in a subterranean mosque in one of the inner courts of the fortress-palace of Agra.

Shah Jehan lived seven years in this subterranean mosque and, when he felt the approach of death, he asked to be moved to the "jasmine Pavilion", a tower of lace-like marble on the fortress wall, which had contained the favourite room of the Empress Arjumand Banu. Shah Jahan breathed his last on the balcony of the "Jasmine Pavilion" overlooking the Jumna, whence the Taj Mahal can be seen in the distance.

Such, briefly, is the history of the Taj Mahal. Since these days the mausoleum of the Empress has survived many vicissitudes of fortune. During the constant wars that took place in India in the 17th and 18th centuries, Agra changed hands many times and was frequently pillaged. Conquerors carried off from the Taj Mahal the great silver doors and the precious lamps and candlesticks, and they stripped the walls of their ornaments of precious stones. The building itself, however, and the greater part of the interior decoration has been preserved.

In the thirties of the 19th century, the British Governor-General proposed to sell the Taj Mahal for demolition, but it has now been restored and is carefully guarded.

I arrived at Agra in the evening and decided to go at once to see the Taj Mahal by moonlight. It was not full moon, but there was sufficient light.

Leaving the hotel, I drove for a long time through the European part of Agra, along broad streets all running between gardens. At last we left the town and, driving through a long avenue, on the left of which the river could be seen, we came out upon a broad square paved with flagstones and surrounded by red stone walls. In the walls, right and left, were gates with high towers. My guide explained that the gate on the right led into the old town, which had been the private property of the Empress Arjumand Banu, and remains in almost the same state as it was during her lifetime. The gate in the left-hand tower led to the Taj Mahal.

It was already growing dark, but in the light of the broad crescent of the moon every line of the buildings stood out distinctly against the pale sky. I walked in the direction of the high dark-red gate-tower with its arrow-shaped arch and horizontal row of small white characteristically Indian cupolas surmounted by sharp-pointed spires. A few broad steps led from the square to the entrance under the arch. It was quite dark there. My footsteps along the mosaic paving echoed resoundingly in the side niches from which stairways led up to a landing on the top of the tower, and to the museum which is inside the tower.

Through the arch the garden is seen: a large expanse of verdure, and in the distance some white outlines resembling a white cloud that has descended and taken symmetrical forms. These were the walls, cupolas, and minarets of the Taj Mahal.

I passed through the arch on to the broad stone platform and stopped to look about me. Straight in front of me and right across the garden led a long broad avenue of dark cypresses, divided down the middle by a strip of water with a row of jutting arms of fountains. At the further end, the avenue of cypresses was closed by the white cloud of the Taj Mahal. At the sides of the Taj and a little below it, the cupolas of two large mosques could be seen under the trees.

I walked slowly in the direction of the white building along the main avenue by the strip of water with its fountains. The first thing that struck me, and that I had not foreseen, was the immense size of the Taj. It is in fact a very large structure, but it appears even larger than it is owing chiefly to the ingenious design of the builders, who surrounded it with a garden and so arranged the gates and avenues that from this side the building is not seen all at once, but is disclosed little by little as you approach it. I realised that everything about it had been exactly planned and calculated and that everything was designed to supplement and reinforce the chief impression. It became clear to me why it was that in photographs the Taj Mahal had appeared unfinished and almost plain. It cannot be separated from the mosques on either side, which appear as its continuation. I saw now why the minarets at the corners of the marble platform on which the main building stands had given me the impression of a defect, for in photographs I had seen the picture of the Taj as ending on both sides with these minarets. Actually, it does not end there, but imperceptibly passes into the garden and the adjacent buildings. Again, the minarets are not actually seen in all their height as they are in the photographs. From the avenue along which I walked, only their tops were visible behind the trees.

The white building of the mausoleum itself was still far away. As I walked towards it, it rose before me higher and higher. Though in the uncertain and changing light of the crescent moon I could distinguish none of the details, a strange sense of expectation forced me to continue to look intently, as if something was about to be revealed to me.

In the shadow of the cypresses it was nearly dark; the garden was filled with the scent of flowers, above all with that of jasmine, and peacocks were mewing. This sound harmonised strangely with the surroundings and somehow still further intensified the feeling of expectation which was coming over me.

Already I could see, brightly outlined in front of me, the central portion of the Taj Mahal rising from the high marble platform. A little light glimmered through the doors.

I reached the middle of the path leading from the arched entrance to the mausoleum. Here, in the centre of the avenue, is a square tank with lotuses in it and with marble seats on one side.

In the faint light of the half moon the Taj Mahal appeared luminous. Wonderfully soft, but at the same time quite distinct, white cupolas and white minarets came into view against the pale sky, and seemed to radiate a light of their own.

I sat on one of the marble seats and looked at the Taj Mahal, trying to seize and impress on my memory all the details of the building itself as I saw it and of everything else around me.

I could not have said what went on in my mind during this time, nor could I have been sure whether I thought about anything at all; but gradually, growing stronger and stronger, a strange feeling stole over me which no words can describe.

Reality, that everyday actual reality in which we live, seemed somehow to be lifted, to fade and float away; but it did not disappear, it only underwent some strange sort of transformation, losing all actuality; every object in it, taken by itself, lost its ordinary meaning and became something quite different. In place of the familiar habitual reality, another reality opened out, a reality which we usually neither know nor see nor feel, but is the one true and genuine reality.

I feel and know that words cannot convey what I wish to say. Only those who have themselves experienced something of the kind, who know the "taste" of such feelings, will understand me.

Before me glimmered the small light in the doors of the Taj Mahal. The white cupolas and white minarets seemed to stir in the changing light of the half moon. From the garden came the scent of jasmine and the mewing of the peacocks.

I had the sensation of being in two worlds at once. In the first place, the ordinary world of things and people had entirely changed, and it was ridiculous even to think of it, so imaginary, artificial, and unreal did it appear now. Everything that belonged to this world had become remote, foreign, and unintelligible to me and I myself most of all, this very "I" that had arrived two hours before with all sorts of luggage and had hurried off to see the Taj Mahal by moonlight. All this and the whole of the life of which it formed a part seemed a puppet show which, moreover, was most clumsily put together and crudely painted, thus not resembling any reality whatsoever. Quite as grotesquely senseless and tragically ineffective appeared all my previous thoughts about the Taj Mahal and its riddle.

The riddle was here before me, but now it was no longer a riddle. It had been made a riddle only by that absurd, non-existent reality from which I had looked at it. Now I experienced the wonderful joy of liberation, as if I had come out into the light from some deep underground passage.

Yes, this was the mystery of death! But it was a revealed and visible mystery. There was nothing dreadful or terrifying about it. On the contrary, it was infinite radiance and joy.

Writing this now, I find it strange to recall that there was scarcely any transitional state. From my usual sensation of myself and everything else, I passed into this new state immediately while I was in this garden, in the avenue of cypresses, with the white outline of the Taj Mahal in front of me.

I remember that an unusually rapid stream of thoughts passed through my mind, as if they were detached from me and choosing or finding their own way.

At one time my thought seemed to be concentrated upon the artists who had built the Taj Mahal. I knew that they had been Sufis whose mystical philosophy, inseparable from poetry, has become the esotericism of Mohammedanism and expresses the ideas of eternity, unreality, and renunciation in brilliant and luxuriant forms of passion and joy. Here the image of the Empress Arjumand Banu and her memorial, "the most beautiful", became by their invisible sides connected with the idea of death, yet death not as annihilation, but as a new life.

I got up and walked forward with my eyes on the light glimmering in the doors, above which rose the immense shape of the Taj Mahal.

Suddenly, quite independently of me, something began to be formulated in my mind.

The light, I knew, burned above the tomb where the body of the Empress lay. Above it and around it are the marble arches, cupolas, and minarets of the Taj Mahal which carry it upwards, merging it into one whole with the sky and the moonlight.