A New Model of the Universe

by P D Ouspensky

Chapter XI — Eternal Recurence and

The Laws of Manu

The fundamental problems of being, that is, the enigmas of birth and death, of coming into existence and of disappearance, never leave man. Whatever he may think about, he is actually thinking of these enigmas or problems. Even when he decides with himself to leave these questions alone, in reality he seizes upon every possibility, even the most remote, and tries once more to understand something in the enigmas which he had realised to be insoluble.

Speaking generally, by their attitude towards the problems of life and death people can be divided into two categories. Most people approach these problems just as they approach other problems and somehow solve them for themselves either positively or negatively. In order to arrive at these solutions, they use ordinary methods of thought and the same categories of thought as they use for thinking of the ordinary things that happen in life. They say either that after death there will be nothing, that beyond the threshold of death there is not and cannot be any existence; or else, that there will be an existence of some sort, either entirely of suffering or entirely of joy.

But others know more than that. They realise that the problems of life and death cannot be approached in an ordinary way; that it is impossible to think of these problems in the same forms in which people think of something that happened yesterday or will happen tomorrow. But they do not go further than this. They feel that it is impossible, or at any rate useless, to think of these things simply, but they do not know what it means to think otherwise than simply.

In order to arrive at a right attitude towards these problems, it is necessary to remember that they are connected with the idea of time. We understand these problems to the extent to which we understand time.

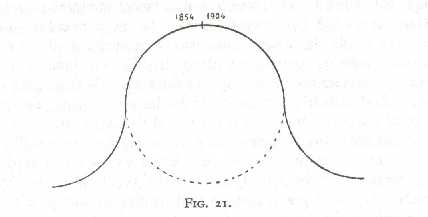

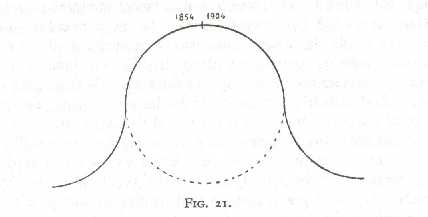

From the ordinary standpoint, man's life is taken as a line from birth to death. A man was born in 1854, lived fifty years, and died. [Fig. 11.1] But where he was before 1854 and where he may be after 1904 is not known. This is the general formulation of all questions of life and death.

From the ordinary standpoint, man's life is taken as a line from birth to death. A man was born in 1854, lived fifty years, and died. [Fig. 11.1] But where he was before 1854 and where he may be after 1904 is not known. This is the general formulation of all questions of life and death.

Science and philosophy do not take these questions seriously, and consider them naïve.

Religious teachings and various pseudo-occult and theosophical systems claim to know the solutions of these problems.

In reality, of course, no one knows anything.

Table of Contents

The mystery of existence before death and existence after death, if there is such existence, is the mystery of time, and "time" guards its secrets better than many people think. In order to approach these mysteries, it is necessary first to understand time itself. All ordinary attempts to answer questions about "what was before" and "what will be after" are based on the ordinary conception of time. [fig. 11.2]

The mystery of existence before death and existence after death, if there is such existence, is the mystery of time, and "time" guards its secrets better than many people think. In order to approach these mysteries, it is necessary first to understand time itself. All ordinary attempts to answer questions about "what was before" and "what will be after" are based on the ordinary conception of time. [fig. 11.2]

The same formula can be applied to problems of existence before birth and after death, whenever such existence is admitted, i.e., the formula is taken thus: [fig. 11.3]

The same formula can be applied to problems of existence before birth and after death, whenever such existence is admitted, i.e., the formula is taken thus: [fig. 11.3]

It is precisely here that the fundamental mistake lies. Time in the sense of before, now, after, is the product of our life, of our being, of our perception and, above all, of our thinking. Outside this life, outside the usual perception, the interrelation of the three phases of time can change; in any case we have no guarantee that it will remain the same. Yet in ordinary thought — including religious, theosophical, and "occult" thought — this question is never even raised. "Time" is regarded as something which is not subject to discussion, as something which belongs to us once and for all, which cannot be taken away from us, and which is always the same. Whatever may happen to us, "time" will always belong to us — and not only "time", but even "eternity".

Neither do we know what eternity is, and we take it to be an infinite extension of time — which really renders the term "eternity" quite unnecessary.

Table of Contents

In the 19th century, certain Eastern and pseudo-Eastern theories began to penetrate Western thought — among others the idea of "reincarnation", that is, of the periodical reappearance on Earth of the same souls. This idea was not entirely unknown before, but belonged to hidden mystical thought. The popularisation of this idea is chiefly due to modern theosophy with all its ramifications.

The origin of the idea of reincarnation as it is expounded in modern theosophy is open to argument. It was adopted by the theosophists practically without alteration from the cult of Krishna, which is a religion of Vedic origin considerably retouched by reformers. But even the cult of Krishna does not contain the "democratic principle" of general and equal reincarnation which is so characteristic of modern theosophy. In the real cult of Krishna only heroes, leaders, and teachers of humanity reincarnate. Reincarnation for the masses, for the crowd, for "householders", assumes much vaguer forms.

Table of Contents

Side by side with the idea of reincarnation, there exists in India the idea of the "transmigration of souls", i.e. the reincarnation of the souls of human beings into animals. The idea of the transmigration of souls connects reincarnation with reward and punishment. Theosophists regard the transmigration of souls as a distortion of the idea of reincarnation by popular beliefs, but this can in no way be regarded as certain. Both the idea of reincarnation and belief in the transmigration of souls may be regarded as having originated from one common source, namely, the teaching of the repetition of everything and of eternal recurrence.

The idea of the eternal recurrence of things and phenomena, the idea of eternal repetition, is connected in European thought with the name of Pythagoras and with the vague notions of the periodicity of the Universe which are found in Indian philosophy and cosmogony. This idea of periodicity cannot be clear to European thought because it becomes complete and connected only with the aid of oral commentaries which, up to the present time, have never and nowhere been made public.

The "life of Brahma", the "days and nights of Brahma", the "breath of Brahma", kalpas and manvantaras: all these ideas are very obscure for European thought, but by their inner content they are invariably associated with Pythagorean ideas of eternal recurrence.

The name of Gautama the Buddha who was almost, if not exactly, a contemporary of Pythagoras and who also taught eternal recurrence, is very seldom mentioned in connection with this idea, in spite of the fact that in Buddha's teaching of the "wheel of lives" the idea is clearer than anywhere else — although it is obscured almost beyond recognition by ignorant interpretations and translations.

Nietzsche contributed a great deal to the popularisation of the idea of eternal recurrence, but he has added nothing new to it. On the contrary, he introduced several wrong concepts into it, as for instance his calculation, which mathematically is altogether wrong, of the mathematical necessity for the repetition of identical worlds in the Universe.

[Nietzsche attempts to prove the necessity for repetition in Euclidean space, and in ordinary, i.e. one-dimensional, time. His understanding of the idea of repetition was that somewhere in the infinite space of the Universe, an Earth exactly like the one we live on must be repeated. Then the same causes will create the same effects; and as a result there will be a room somewhere, exactly like that in which I am sitting, and in that room a man exactly like me with an exactly similar pen will write what I am writing now. Such a construction is possible only with a naïve understanding of time.

Nietzsche proves the necessity for repetition roughly in the following way. According to him, if we take a certain number of units and examine their possible combinations, the combinations that occurred once are bound to recur in the course of time. If the number of units is large, repetitions will be more frequent, and if the number of units is infinite, everything is bound to repeat.

This is in fact wrong simply because Nietzsche fails to see that the number of possible combinations will grow in a much higher ratio than the number of units. Consequently, the number of possible repetitions, instead of increasing, will diminish. Thus, with a certain, not even infinite but merely large, number of units, the number of combinations will be infinite and the probability of repetition will equal zero. Given an infinite number of units, even the possibility of repetition is out of the question. — PDO.]

But though he made mistakes in the attempts to prove his theories, Nietzsche emotionally felt the idea of eternal recurrence very strongly. He felt the idea as a poet. Several passages in his Zarathustra, and in other books where he touches upon the idea, are perhaps the best he ever wrote.

But repetition cannot be proved on our plane, that is, in the three-dimensional world with time as the fourth dimension, no matter whether time is taken as a real or as an imaginary quantity. Repetition requires five dimensions, i.e. an entirely new "space-time-eternity".

The Pythagorean ideas of the repetition of everything were referred to among others by Eudemus, a pupil of Aristotle. Eudemus' Physics has been lost, and what he wrote about the Pythagoreans is known to us only through the later commentaries of Simplicius. It is very interesting to observe that, according to Eudemus, the Pythagoreans distinguished two kinds of repetition.

Simplicius wrote:

The Pythagoreans said that the same things are repeated again and again.

In this connection it is interesting to note the words of Eudemus, Aristotle's disciple (in the 3rd book of Physics). He says: "Some people accept and some people deny that time repeats itself. Repetition is understood in different senses. One kind of repetition may be in the natural order of things, like repetition of summers and winters and other seasons, when a new one comes after another has disappeared; to this order of things belong the movements of the heavenly bodies and the phenomena produced by them, such as solstices and equinoxes, which are produced by the movement of the Sun."

But if we are to believe the Pythagoreans, there is another kind of repetition in quantity, in which the same things exist a number of times. That means that I shall talk to you and sit exactly like this and I shall have in my hand the same stick, and everything will be the same as it is now. This makes it possible to suppose that there exists no difference in time, because if movements (of heavenly bodies) and many other things are the same, what occurred before and what will occur afterwards are also the same. This applies also to their number, which is always the same. Everything is the same and therefore time is the same.

The preceding passage from Simplicius is particularly interesting in that it gives a key for the translation of other Pythagorean fragments, that is, notes on Pythagoras and his teaching, which have been preserved in certain authors. The basis of the view on Pythagoras which is accepted in textbooks of the history of philosophy is the idea that in the philosophy of Pythagoras and in his conception of the world, the chief place was occupied by number. In reality, it is simply a bad translation. The word "number" is in fact constantly met with in Pythagorean fragments — but only the word. In most cases this word is always translated as having independent significance, which entirely distorts its meaning. The preceding passage from Simplicius loses all meaning in the usual translation.

These two kinds of repetition, which Eudemus called repetition in the natural order of things and repetition in number of existences, are, of course, repetition in time and repetition in eternity. It follows from this that the Pythagoreans distinguished these two ideas, which are confused by modern Buddhists and were confused by Nietzsche.

Table of Contents

Jesus undoubtedly knew of repetition and spoke of it with his disciples. In the Gospels there are many allusions to this, but the most unquestionable passage, which has a quite definite meaning in the Greek, Slavonic, and German texts, has lost its meaning in translations into other languages, which took the most important word from the Latin translation.

And Jesus said unto them, Verily I say unto you, That ye which have followed me in the regeneration .... (Matt. 19:28).

The Greek original can be translated only as repeated existence (again-existence) or repeated birth (again-birth).

In Latin this word was translated regeneratio, which in the first meaning corresponded to repeated birth; but later, owing to the use of the word regeneration (and its derivative) in the sense of renovation, it lost its original meaning.

The Apostle Paul undoubtedly knew of the idea of repetition, but had a negative attitude towards it. The idea was too esoteric for him:

For Christ is not entered into the holy places made with hands....

Nor yet that he should offer himself often, as the high priest entereth into the holy place every year with blood of others;

For then must he often have suffered from the foundation of the world: but now once in the end of the world hath he appeared to put away sin by the sacrifice of himself. (Heb. 9:24-26).

It must be noted that the Epistle to the Hebrews is ascribed to certain other authors as well as to the Apostle Paul, and really there is no definite information on this question.

Origen (3rd century) in his book On First Principles, also refers to the idea of repetition, but speaks of it negatively:

And now I do not understand by what proofs they can maintain their position, who assert that worlds sometimes come into existence which are not dissimilar to each other, but in all respects equal. For if there is said to be a world similar in all respects (to the present), then it will come to pass that Adam and Eve will do the same things which they did before: there will be a second time the same deluge, and the same Moses will again lead a nation numbering nearly six hundred thousand out of Egypt; Judas will also a second time betray the Lord; Paul will a second time keep the garments of those who stoned Stephen; and everything which has been done in this life will be said to be repeated. [The writings of Origen tr. Rev Frederick Crombie, Edinburgh, 1878 — PDO]

At the same time Origen was very near to the correct understanding of eternity, and it is possible that he denied the idea of repetition not quite sincerely. It is very probable that because of the conditions of his time this idea could not be introduced without being denied.

It is, however, an interesting fact that this idea was known in the first centuries of Christianity, but it entirely disappeared from "Christian thought".

Table of Contents

If we try to trace the idea of eternal recurrence in European literature, it is necessary to mention the remarkable "fable" by R L Stevenson, The Song of the Morrow (1895); and C H Hinton's story, "An Unfinished Communication" in the second book of his Scientific Romances (1898), and also one or two pages in his story "Stella" in the same book.

There are also two interesting poems on the same subject. One is by Alexis Tolstoy:

Through the slush and the ruts of the roadway—

By the side of the dam of the stream;

Where the wet fishing nets are drying,

The carriage jogs on, and I muse.

I muse and I look at the roadway,

At the damp and the dull grey weather,

At the shelving bank of the lake,

And the far-off smoke of the villages.

By the dam, with a cheerless face,

Is walking a tattered old Jew.

From the lake, with a splashing of foam,

The waters rush through the weir.

A little boy plays on a pipe,

He has made it out of a reed.

The startled wild ducks have flown,

And call as they sweep from the lake.

Near the old tumbling-down mill

Some labourers sit on the grass.

An old worn horse in a cart

Is lazily dragging some sacks.

And I know it all, oh! so well,

Though I never have been here before,

The roof there, far away yonder,

And the boy, and the wood, and the weir,

And the mournful voice of the mill,

And the crumbling barn in the field —

I have been here and seen it before,

And forgotten it all long ago.

This very same horse plodded on.

It was dragging the very same sacks;

And under the mouldering mill

The labourers sat on the grass.

And the Jew, with his beard, walked by,

And the weir made just such a noise.

All this has happened before,

Only, I cannot tell when.

—Translated by the Hon. Maurice Baring, The Oxford Book of Russian Verse.

The other poem is by D G Rossetti:

Sudden Light

I have been here before,

But when or how I cannot tell:

I know the grass beyond the door,

The sweet keen smell,

The sighing sound, the lights around the shore.

You have been mine before—

How long ago I may not know:

But just when at that swallow's soar

Your neck turn'd so,

Some veil did fall — I knew it all of yore.

Then, now — perchance again!

O round mine eyes your tresses shake!

Shall we not lie as we have lain

Thus for Love's sake,

And sleep, and wake, yet never break the chain?

There is a variant to the last stanza:

Has this been thus before

And shall not thus time's eddying flight

Still with our lives our love restore

In death's despite

And day and night yield one delight once more?

Both poems were written in the fifties of the 19th century.

Tolstoy's poem is usually regarded as simply recording strange passing moods. But Tolstoy, who was much interested in mystical literature and was in contact with several occult circles which existed in Europe at his time, may quite definitely have known of the idea of eternal recurrence.

The feeling of the repetition of events was very strong in Lermontoff. He is full of presentiments, expectations, "memories". He constantly alludes to these sensations, especially in his prose. The Fatalist is practically written on the theme of repetition and of remembering that which seems to have happened in some unknown past. Many passages in The Princess and in Bela, especially the philosophical digressions, produce the impression that Lermontoff is trying to remember something that he has forgotten.

We think in general that we know Lermontoff. But who has asked himself what the following passage in Bela means?

...I was exhilerated to feel myself so high above the world. It was a childish feeling, of course, but when we get away from artificial conditions and approach nearer to Nature we cannot help becoming children. All that we have acquired falls away from our being and we become once more what we were and what we shall one day assuredly be again. [A Hero of our Time, by M Y Lermontoff. London, 1928. — PDO]

Personally I do not remember a single attempt to analyse these words in all the literature on Lermontoff. But the idea of the possibility of some kind of "return" undoubtedly disturbed Lermontoff, now carried him away, now appeared an unrealisable dream:

Would it not be better to finish the path of life in self-forgetting

And to fall into an unending sleep

Looking for a near awakening?

("Valerik".)

In our time the idea of recurrence, and even of the possibility of half-conscious remembering, becomes more and more pressing and necessary.

In the Life of Napoleon (1928), D S Merejhovsky constantly alludes to Napoleon in the phrases "he knew" ("remembered"). And later, in dealing with Napoleon's last years in Europe, "he forgot" ("he ceased to remember").

This list does not claim to be complete. I wished only to show that the idea of repetition and recollection of the past which is not in our time is far from being foreign to Western thought.

But the psychological apprehension of the idea of eternal recurrence does not necessarily lead to a logical understanding and explanation of it. In order to understand the idea of eternal recurrence and its different aspects, it is necessary to go back to the ideas of the A New Model of the Universe.

Table of Contents

The idea of time as the fourth dimension does not contradict the ordinary views of life so long as we take time as a straight line. This idea only brings with it a sensation of greater pre-ordination, of greater inevitability. But the idea of time as a curve of the fourth dimension entirely changes our conception of life. If we clearly understand the meaning of this curvature, and especially when we begin to see how the curve of the fourth dimension is transformed into the curves of the fifth and the sixth dimensions, our views of things and of ourselves cannot any longer remain what they were.

As was said in the preceding chapter, according to the initial scheme of dimensions, in which dimensions are still taken as straight lines, the fifth dimension is a line perpendicular to the line of the fourth dimension and intersecting it, that is, a line which passes through every moment of time, the line of the infinite existence of a moment.

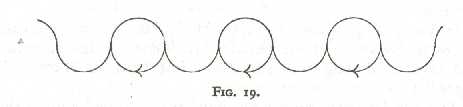

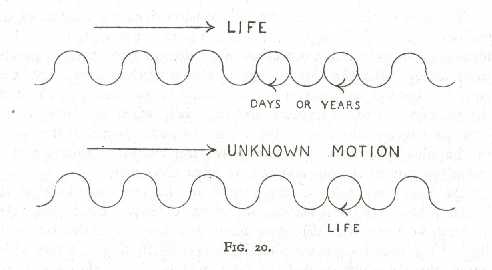

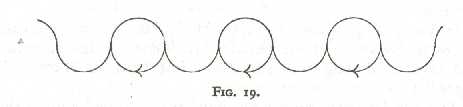

But how is this line formed, where does it come from, and what follows from it? This can be understood to a certain extent if life is taken as a series of undulatory vibrations.

As we should know from the study of undulatory vibrations in the world of physical phenomena, every wave comprises in itself a complete circle, that is, the matter of the wave moves in a completed curve in the same place and for as long as the force acts which creates the wave.

We should know also that every wave consists of smaller waves and is in its turn a component part of a bigger wave.

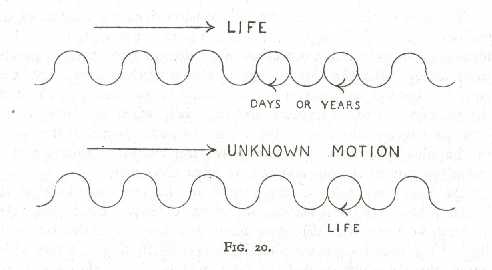

If, simply for the sake of argument, we take days as the smaller waves which form the bigger waves of years, then the waves of years will form one great wave of life. And so long as this wave of life rolls on, the waves of days and the waves of years must rotate at their appointed places, repeating and repeating themselves. [Fig. 19] Thus the line of the fourth dimension, the line of life or time, consists of wheels of ever-repeating days, of small circles of the fifth dimension, just as a ray of light consists of quanta of light, each rotating in its place so long as the primary shock which sends forth the particular ray persists. But in itself a ray may be a curve, a component part of some bigger wave.

The same applies to the line of life. [Fig. 20] If we take it as one great wave consisting of the waves of days and years, we shall have to admit that the line of life moves in a curve and makes a complete revolution, coming back to the point of its departure. If a day or a year is a wave in the undulatory movement of our life, then our whole life is a wave in some other undulatory movement of which we know nothing.

As I have already pointed out, in our ordinary conception life appears as a straight line drawn between the moments of birth and death.

But if we imagine that life is a wave, we shall get this figure: [Fig. 21]

The point of death coincides with the point of birth.

For one who has followed the development of the ideas which touch on "dimensions of time" in the preceding chapter and in this one, this point does not present any difficulty but on the contrary results naturally from all that has already been said.

But usually after this point there comes a question which is more difficult to answer, namely, how an identical relation between the births of different people is preserved when we know that the relation between their deaths is quite different, i.e., that it does not correspond with the relation of their births. To put it more shortly, what will happen to a man who has died before his grandmother? He must be born immediately, and his mother is as yet unborn.

Two answers are possible. First, it is possible to say that at the moment when the soul touches infinity, different relations of time become adjusted, because a moment of eternity can have different time values. Second, it is possible to say that our usual conceptions of "dimensions of time" are wrong. For instance, for us time can have different duration — five years, ten years, a hundred years — but it always has the same speed. But where are the proofs of this? Why not suppose that time in certain limits (for instance in relation to human life) always has the same duration but different speed? One is not more arbitrary than the other, but with the admission of this possibility the question disappears.

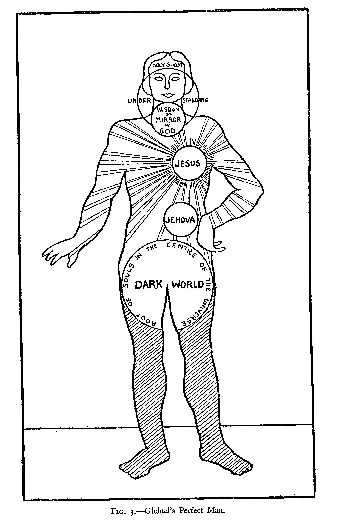

In Tertium Organum I gave a drawing of the figure of the fourth dimension taken from a book by Van Manen. This figure consists of two circles, one inside the other. It is the figure of life. The small circle stands for man; the large circle for the life of man. The small circle rolls inside the large circle which first widens, then gradually becomes more narrow and brings the small circle to the same point from which it started. In rolling along the large circle the small circle rotates on its own axis. This rotation is eternity in relation to time, which is movement along the large circle.

In Tertium Organum I gave a drawing of the figure of the fourth dimension taken from a book by Van Manen. This figure consists of two circles, one inside the other. It is the figure of life. The small circle stands for man; the large circle for the life of man. The small circle rolls inside the large circle which first widens, then gradually becomes more narrow and brings the small circle to the same point from which it started. In rolling along the large circle the small circle rotates on its own axis. This rotation is eternity in relation to time, which is movement along the large circle.

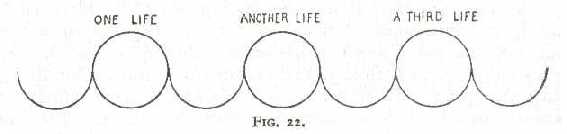

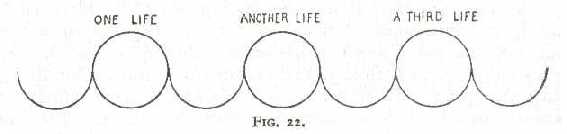

Here again we have what appears to be a paradox — the fifth dimension inside the fourth dimension; movement along the fifth dimension creating movement along the fourth dimension. How are we to find the beginning and the end? Which is the driving force? Which is driven? Is it the small circle that rotates driven by the shock which sends it round the large circle, or is it the large circle itself which is driven by the rotation of the small circles? The one drives the other. But in relation to life taken as the large circle, eternity is to be found: first, in the small circles of repeating moments, days and years; and, second, in the repetition of the large circle itself, in the repetition of life, that is, in the repetition of the waves. [Fig. 22]

Just as in the case of the fourth dimension, we are again faced with the fact that a higher dimension is both above and below the lower dimension.

As above, so below.

The fourth dimension for us lies in the world of celestial bodies and in the world of molecules.

Table of Contents

The fifth dimension lies in the moments of life eternally remaining where they are, and in the repetition of life itself, taken as a whole.

Life in itself is time for man. For man there is not, and cannot be, any other time outside the time of his life. Man is his life. His life is his time.

The way of measuring time, for all, by means of such phenomena as the apparent or real movement of the Sun or the Moon, is comprehensible and practically convenient. But it is generally forgotten that this is only a formal time accepted by common agreement. Absolute time for man is his life. There can be no other time outside this time.

If I die today, tomorrow will not exist for me. But, as has been said before, all theories of the future life, of existence after death, of reincarnation, etc., contain one obvious mistake. They are all based on the usual understanding of time, that is, on the idea that tomorrow will exist after death. In reality, it is just in this that life differs from death. Man dies because his time ends. There can be no tomorrow after death. But all usual conceptions of the "future life" require the existence of "tomorrow". What future life can there be if it suddenly appears that there is no future, no "tomorrow", no time, no "after"? Spiritualists, theosophists, theologians, and others who know everything about the future life may find themselves in a very strange situation if the fact is realised that no "after" exists.

What then is possible? What may the meaning of life as a circle be?

I pointed out in the preceding chapter that the very curvature of the line of time implies the presence in it of yet another dimension, namely, the fifth dimension, or eternity. If in the usual understanding, the fourth dimension is extension of time, what can the fifth dimension, or eternity, be?

For our mind, eternity is conceivable only under two forms: under the form of co-existence or under the form of repetition. The form of co-existence requires space conceptions — somewhere there exist things identical with those here: identical people, an identical world. The form of repetition requires time conceptions: some time everything is repeated or will be repeated, either immediately after the completion of the particular cycle, that is, of the particular life, or after every moment. The latter, i.e., the immediate repetition of every moment again and again, brings this idea near the idea of co-existence. But for our mind, it is more convenient to think of the idea of repetition in the form of the repetition of cycles. One life ends and another begins. One time ends and another begins. Death is really a return to the beginning.

This means that if a man was born in 1877 and died in 1912; then, having died, he finds himself again in 1877 and must live the same life all over again. In dying, in completing the circle of life, he enters the same life from the other end. He is born again in the same town, in the same street, of the same parents, in the same year, and on the same day. He will have the same brothers and sisters, the same uncles and aunts, the same toys, the same kittens, the same friends, the same women. He will make the same mistakes, laugh and cry in the same way, rejoice and suffer in the same way. And when the time comes he will die in exactly the same way as he did before, and again at the moment of his death it will be as though all the clocks were put back to 7.35 a.m. on the 2nd September, 1877, and from this moment started again with their usual movement.

The new life begins in exactly the same conditions as the preceding one, and it cannot begin in any other conditions. The only thing that can and must be admitted is the fact of the strengthening with every life of the tendencies of the preceding life, of those tendencies which grew and increased during life, both bad and good tendencies, those which were a manifestation of strength and those which were a manifestation of weakness.

There exists, indeed, much more psychological material for the idea of eternal recurrence than is supposed, but the existence of this material is not fully recognised by scientific thought.

Everybody knows the sensation, or descriptions of the sensation, that is sometimes experienced by people, especially in childhood, the sensation that this has happened before. The two poems quoted earlier could have been inspired by the same sensation.

I spoke of this sensation in the chapter on dreams, and I pointed out that the usual explanations account for two categories of this sensation but leave the third category unexplained. The third category is characterised by the fact that the sensation that this has happened before, though very vivid and frequent in childhood, disappears in adult life. In some cases, this special kind of foreknowledge of people, things, places, and events can be verified and established. The very rare "trustworthy" cases of clairvoyance belong to such foreknowledge.

But in itself, the fact of these accidental recollections, even if they are really recollections, is too small to allow anything to be built on it.

A man may be perfectly justified in asking: "If such a tremendous phenomenon as the repetition of lives really exists, why do we know nothing of it, why do we not remember more? And why did people not realise it long ago, why is it only now presented to us as a new discovery?

All these questions are well founded; but it is not difficult to answer them.

Earlier in this book, the transformation of a butterfly was given as an example of evolution. What is especially characteristic for us in the transformation of a butterfly from the point of view in question is the fact that in passing to a new level of transformation the "butterfly" completely vanishes from the preceding level, dies on the preceding level, ceases to exist there — that is, loses all connection with its former existence. If a butterfly sees and learns more, it is unable to tell the caterpillars anything about it. It is already dead as a caterpillar, it has vanished from the world of caterpillars.

Something analogous must happen to people to whom the mysteries of time and eternity are revealed. They know and can speak of what they know, but people will neither hear nor understand them.

Why have people not realised long ago the truth of the idea of eternal recurrence?

But they did in fact realise it long ago. I have pointed to the teaching of Pythagoras, to Buddhism, to theories of reincarnation and transmigration of souls, which are actually only distortions of the idea of eternal recurrence. Many other ideas of the future life, various allusions to "occult" teachings (for instance the very strange idea of the possibility of changing the past), various popular beliefs — such as the cult of ancestors; all these are connected with the idea of recurrence.

It is quite clear that the idea of recurrence cannot be popular in its pure form, if only because it seems absurd from the standpoint of ordinary "three-dimensional" sensations and the usual view of time, which leaves no place for recurrence. On the contrary, according to the ordinary wisdom of the world, "nothing ever returns". So even in those teachings in which the idea of recurrence originally undoubtedly existed in its pure form, as for example in Buddhism, it has become distorted and adapted to the usual understanding of time. According to recent interpretations of learned Buddhists, a man is born into a new life at the very moment of his death. But this is a continuation in time. Buddhists have rejected the "absurd" idea of a return into the past, and their "wheel of lives" rolls along with the calendar. Certainly in this way they have taken away all force from the idea, but they have made it acceptable to the masses and capable of logical explanation and interpretation.

In speaking of the idea of eternal recurrence, it is necessary to understand that it cannot be proved in the ordinary way, that is, by the usual methods of observation and verification. We know but one line of time, the one on which we now live. We are one-dimensional beings in relation to time; we have no knowledge of parallel lines. Suppositions as to the existence of parallel lines cannot be proved so long as we remain on one line. In Tertium Organum I described what the universe of one-dimensional beings must be. These beings know nothing besides their own line. If they supposed the existence of something new, something they did not know before, for them it would have to be on their own line, either in front of them or behind them. Our position in relation to time is exactly the same. Everything that exists must occupy a certain place in time either in front of us or behind us. There can be nothing parallel to us. This means that we cannot prove the existence of anything parallel so long as we remain on our line. But if we attempt to break away from ordinary views and bear in mind that the supposition of the possible existence of other lines of "time" parallel to ours is more "scientific" than the usual naïve one-dimensional conception of time, then the conception of life as a recurring phenomenon will prove to be easier than we imagine.

Ordinary views are based upon the assumption that the life of a man, that is, the whole of his inner world, his desires, tastes, sympathies, tendencies, habits, inclinations, capacities, talents, vices, arise out of nothing and vanish into nothing. Christian teachings speak of the possibility of a future life, that is, of life beyond the grave, but they do not speak of life before birth. According to their view, "souls" are born with bodies. In actual fact, however, it is very difficult to think of life (that is, of the soul) or of the inner being of man, as a being that arises out of nothing. It is much easier to think that this being existed earlier, before birth. But people do not know how to begin thinking in this direction. The theosophical theories of reincarnation which try to stretch the life of an individual man along the line of the life of the Earth will not bear criticism from the point of view of a rightly understood idea of time.

There exist dozens, perhaps even hundreds, of various ingenious theories which claim to explain all the angles and curves of man's inner world by a combination of hereditary influences and the suppressed voices of hidden inner instincts. All these theories are acceptable, each in its own way, but none of them explains everything in man. One theory explains one thing better, another explains another thing better. But much, very much, remains unexplained. It could not be otherwise: for theories of heredity, even of a dim faraway heredity, theories of hidden instincts, of unconscious memory, can explain certain sides of man; but other sides they cannot explain. Until we find it possible to recognise that we have lived before, very much will remain in us that we shall never be able to understand.

It is very difficult to accept the idea of the absolute and inevitable repetition of everything. It seems to us that if we were to remember at least something, we should be able to avoid some of the most unpleasant things. Moreover the idea of absolute repetition does not agree with the idea of growing tendencies, which is also necessary.

Table of Contents

In this connection it must be recognised that as regards the character of the repetition of their lives, people fall into several types or categories.

There are people of absolute repetition in whose case everything, both big and little, is transmitted from one life to another.

There are people whose lives have the same beginning each time, but go on with slight variations, upwards or downwards, coming to approximately the same end.

There are people in whose case lives go with a definitely ascending tendency, becoming richer and stronger outwardly.

There are people whose lives, on the contrary, display a clearly marked descending line, which gradually destroys all that is alive in them and reduces them to nothing.

There are people whose life contains an inner ascending line, which gradually leads them out of the circle of eternal repetition and causes them to pass to another plane of being.

Let us first examine the type of lives in which absolute repetition is inevitable.

These are, first of all, people of byt [An untranslatable Russian word, signifying in its first meaning life in relation to external forms; in its second meaning, as used in literature, it means life in firmly established forms — peasants' byt; country landowners' byt; "byt circumstance". The word is very largely used in connection with the theatre — byt play, byt actor (different from a character actor), byt voice, byt intonation or inflexions. — PDO.] of deeply-rooted, petrified, routine life. Their lives succeed one another with the monotony of the hand of the clock moving on the dial. There can be in their lives nothing unexpected, nothing accidental, no adventures. They are born and die in the same house where their fathers and grandfathers were born and died and where their children and grandchildren will be born and will die. National calamities, wars, earthquakes, plagues, sometimes wipe out hundreds of thousands of them from the face of the Earth at one stroke. But apart from such events, their whole life is strictly ordered and organised on a plan.

Let us imagine a merchant in an old Eastern town living in the fixed conditions of the established routine life which has gone on unchanged for whole centuries. He sells carpets in the same shop where his father and grandfather, and probably his great-grandfather, sold carpets. His whole life from birth to death can be seen as on a map. In a certain year he takes a wife, in a certain year he wins a lawsuit against his neighbour, always using the same transparent manoeuvre, and always in the same year, day, and hour he dies, always of the same cause, of having eaten too much pilaff.

There can be no new events in the lives of such people. But it is just this absoluteness of repetition that creates in them some vague consciousness of the inevitability of everything that happens, a belief in fate, fatalism, and, at times, a strange sort of wisdom and calmness, in some cases passing into a kind of ironical contempt for people who are restless, seeking for something, striving after something.

To another type of people of the same category of exact repetition belong historical personages: people whose lives are linked with the great cycles of life, that is to say, with the life of peoples, states, countries — great conquerors, reformers, leaders of the masses, revolutionaries, kings who build up empires, kings who destroy their own or their enemies' great empires, all belong to this category. There can be no change in the lives of these people either. Every word they pronounce affects the destiny of nations. They must know their parts perfectly. They can add nothing of their own, they can omit nothing, they cannot change the meaning of what they have to say.

This type is especially clear if we take weak historical personages, those men whom history puts forward as though intentionally for responsible parts when empires or whole cultures are to be destroyed — such people, for instance, as Louis XVI or Nicholas II.

They do nothing, and they do not want to do anything; they wish only to be left in peace; and yet each movement, each gesture, each word of theirs, even words that seem to be uttered by mistake such as the famous "senseless dreams" [The words of the Emperor Nicholas II which were used by mistake when receiving representatives of the "zemstvos" and towns in 1895. — PDO.]; and all of them, without exception, lead to the ultimate catastrophe. Not a single word can be left out, and even mistakes must be repeated.

"Strong personages" — Napoleon, Caesars, Genghis Khans — are in no way different from weak personages. They are pieces on the same board, and equally they cannot do anything themselves, cannot say one word of themselves, cannot either add or subtract anything from what they must say or do.

In the case also of people who constitute the crowd on the world's stage, repetition is inevitable. The crowd must know its rôle very well at any particular moment. No expression of popular feeling during patriotic manifestations or armed insurrections, during coronations or revolutions, would be possible if the crowd could be ignorant of or forget its rôle. This knowledge is possible only through constant repetition of the same thing.

But if we pass to the separate lives of the people who form the crowd, we shall see that with different people "growing tendencies" produce very different results. "Growing tendencies" may be of two kinds: those which raise the vitality (though only outwardly) and those which lower the vitality.

Let us take the type which lowers the vitality, the type with the growing tendency to degeneration. Failures, drunkards, criminals, prostitutes, suicides belong to this category. With each new life, they "fall" more and more easily, offer less and less resistance. Their vital force gradually weakens, they become living automatons, shadows of themselves, with a single tendency, a single desire, which constitutes their chief passion, their chief vice, or their chief weakness. If their life is linked up with the lives of other people, this link gradually weakens and at last disappears altogether. These people pass slowly out of life. This is exactly what happens to suicides. They are surrounded by an atmosphere of strange fatality and at times do not even live up the moment of their suicide, but begin to die sooner and finally cease to be born.

This is real death, for death exists just as birth exists.

Souls are born and die just like bodies. The birth of all souls is the same. How it occurs is perhaps the greatest mystery in life. But the death of souls may be different. The soul may die on one plane of being and pass to a higher plane of being, and it may die altogether, become gradually reduced to nothing, vanish, cease to be.

To the category of dying souls belong people who are known by their tragic fate and especially by their tragic end. It is to these people that the remarkable rule of the Eleusinian Mysteries referred, a rule that has never been rightly understood and interpreted.

Participation in the Mysteries was barred: first, to criminals; second, to foreigners (that is, barbarians); and finally to people in whose lives great calamities occurred.

This rule has usually been interpreted in the sense that great calamities in people's lives meant the hostility of the gods or the anger of the gods caused by something that those people had done or omitted to do. But in esoteric understanding, it was certainly clear that people whose lives consist of a series of catastrophes could not be admitted to participation in the Mysteries or to initiation, because the fact of these continuous catastrophes showed that they were going down hill and could not be stopped.

In seeming contrast to the descending or unsuccessful type, but in reality in exactly the same position, are people who are successful from the ordinary point of view, but successful through adaptation to the darkest or most senseless sides of life: people who quickly amass enormous fortunes — millionaires and super-millionaires; successful statesmen of opportunist or definitely criminal activities; "scientists" who create bogus theories which become fashionable and arrest the development of true knowledge; "philanthropists" who support all forms of prohibitive legislation; inventors of high explosives and poisonous gases; sports-addicts of every kind and description; prize-fighters, world champions, record-breakers, cinema-clowns, and "stars"; novelists, poets, musicians, painters, actors, who are commercially successful but have no other value; founders of crazy sects, cults, and the like. In each new life, these people continue to do what they did before: spend less and less time on preparatory training; grasp sooner the technique of their business and the technique of success; attain greater and greater celebrity or fame. Some of them become "infant prodigies" and show their special capacities from the earliest years.

The danger for the successful type of people is their success. Success hypnotises them, makes them believe that they themselves are the cause of their success. Success makes them follow the line of least resistance — that is, sacrifice everything to success. Therefore nothing changes in their lives save that success is attained ever more easily and ever more mechanically. Without formulating it, they feel that their strength lies precisely in this mechanicalness and they suppress in themselves all other desires, interests, and inclinations.

Men of real science, real art, real thought or action, differ from these chiefly in very seldom attaining success. As a rule, they begin to be recognised only long after the end of their earthly life. This is an exceedingly favourable factor from the point of view of the repetition of their lives. The inner decomposition, which almost invariably comes with success, never sets in with them. They start each new life striving towards their unattainable aim, every time with new strength, and they sometimes begin and "remember" astoundingly early, like some famous musicians or thinkers.

Evolution — that is, inner growth, inner development — cannot be either accidental or mechanical. The ways of evolution are the ways of Jnana-Yoga, Raja-Yoga, Karma-Yoga, Hatha-Yoga, and Bhakti-Yoga, or the way of the special doctrine accessible only to few, which was mentioned in the chapter on Yoga. The five Yogas and the way of the special doctrine are the ways of work on oneself for people of different inner type; but all the ways are equally difficult, all the ways demand the whole of man.

People of the descending type are excluded from the outset. No evolution is possible for them: for they are incapable of any long and sustained effort, whereas evolution is the result of long and persistent work in a definite direction. In exactly the same position are people of the successful type. People of the failing type are hindered by their failure; people of the successful type are hindered by their success.

For people of the "byt" and for historical personages, evolution is possible only through very difficult, hidden, Karma-Yoga. They can make no outward changes. If by some miracle they begin to realise their position and solve the chief enigma of life, they must play a rôle, must pretend that they do not notice or understand anything. Besides Karma-Yoga, Bhakti-Yoga is possible for them in some cases. Karma-Yoga shows them that it is possible to change inwardly without changing outwardly, and that only the inward change is of importance. This is an extremely difficult way — an almost impossible way — and it requires a great amount of help from somebody who can help.

Table of Contents

For all categories of people, evolution is connected with recollection.

Recollection of an unknown past has been spoken of already. Recollection may be very different in quality and may have very different properties. The evolving individual remembers, although vaguely, his previous lives. But as evolution means escaping from the wheel of the fifth dimension and passing into the spiral of the sixth dimension, recollection has importance only when it bears an active character in a certain definite direction — when it creates discontent with what exists and a longing for new ways.

By this I mean that recollection by itself does not create evolution; on the contrary, it may be the cause of a still worse bondage in life, that is, in the fifth dimension. In these cases, "recollection" takes either "routine life" forms, or pathological forms, hiding itself behind one or another kind of emotional or practical attitude to life.

Sometimes, a man definitely begins to think that he knows what is bound to happen. If he is of the successful type, he ascribes it to his sagacity, astuteness, clearness of mind, and so on. In reality it is all recollection, though unconscious recollection. A man feels that he has already walked along this road; he almost knows what will be beyond the next turning, and naturally in all these cases recollection produces pride, self-assurance, and conceit instead of dissatisfaction.

People of absolute repetition, that is, people of "routine life", and also "historical personages", can sometimes have almost conscious recollection, but it does not awaken them and only binds them more and more to trifles, to things, to customs, to words, to rituals, to gestures, and makes it still more difficult for them to stand apart from themselves and to look at themselves from outside.

A business man explains this recollection by his experience, his capacity to think quickly, to guess correctly; by his "flair"; by his business "instinct"; by his "intuition". In the case of "great" soldiers, statesmen, revolutionary leaders, navigators who discover new lands, inventors, scientists who create new theories, writers, musicians, artists, it is explained by "talent" or "genius" or "inspiration". In some people, recollection evokes mad bravery, or a continual desire to play with their life. They feel that this cannot happen to them, they cannot be killed like other ordinary people. Such are many historical personages, "men of destiny".

With people of the descending type also, recollection can be very vivid — but it only serves to intensify their sense that the ground is crumbling beneath their feet. It intensifies their despair and discontent, which manifest themselves in some cases as hatred, spite, or impotent anguish, and in others as crimes or excesses.

Thus recollection does not by itself lead to evolution; but evolution at a certain stage arouses recollection. In this case, however, recollection is not clouded by a superior or inferior personal interpretation, but becomes more and more conscious.

Table of Contents

This is almost all that can be said about eternal recurrence, making use of material within general reach. There remains to be established the relation of the idea of eternal recurrence to the idea of "reincarnation", as it is treated in some teachings.

I have mentioned before that the idea of reincarnation can be regarded as a distortion of the idea of eternal recurrence. This is true in many cases, although at the same time there are grounds for thinking that the idea of reincarnation has an independent meaning which can be found only in certain allusions contained in Indian scriptures and in a very few authors on later mystical literature.

Before passing to the origin of the idea of reincarnation or of its independent meaning, I want to set forth in a short form some of the best-known interpretations of this idea.

In modern theosophy which, of all Indian teachings, stands nearest to the cult of Krishna, man is regarded as a complex being consisting of "seven bodies". The higher or the finer of these bodies, the seventh, the sixth, and the fifth, are but principles contained in the fourth body. The fourth body of man is immortal and can reincarnate. This means that after the death of the physical body and after the successive "deaths" of the second (the astral) and the third (the mental) bodies, which sometimes live very long after the death of the physical body, the fourth (the causal body) reincarnates in a new human being, born after a considerable lapse of time in entirely different, new, conditions. According to theosophical authors, several hundred years, and very often one or even two thousand years, elapse between one incarnation and another.

It must also be noted that the state of the higher bodies, that is, the astral, the mental, and the causal, is very different at different stages of man's evolution. In a man who is but little developed, even the causal body is hardly more than a principle. It carries with it no recollections. A new reincarnation is, as it were, an independent life. It is only in comparatively high stages of development that the causal body may carry some dim recollections of a former life.

The idea of reincarnation is connected with the idea of "karma". Karma is understood as a chain of causes and effects handed down from one life to another; but into the abstract idea of karma is introduced the idea of retribution. Thus a man's actions towards other people in one life may provoke similar actions on the part of those or of other people towards him in another life; or the same results may be the outcome of accidental causes. Thus, the existence of cripples, or of people suffering from painful and revolting diseases, is explained by the cruelties committed by these people in their past lives. This is supposed to mean that their own suffering redeems suffering caused by them. In reality, in the idea of karma, suffering in itself has no redeeming power; only a man must understand something from suffering, must change inwardly, and must then begin to act in a different way from before. Then the new karma will, so to speak, wipe out the old one, and a man's sufferings will cease.

Other teachings which accept the idea of reincarnation differ from theosophy only formally, in certain details. Thus European "spiritualistic" teachings recognise the possibility of a quicker reincarnation, not after hundreds or thousands of years, but after a few years or months. Modern Buddhism recognises immediate reincarnation after death. In this last case, the reincarnating principle (in view of the fact that the existence of the "soul" is denied in Buddhism) is "the last thought of the dying man".

In all these conceptions of reincarnation, there does not appear to be the slightest doubt regarding the correctness of the usual conception of time. It is this above all which deprives them of all force and significance. Time is taken as though it actually existed and were such as it is conceived to be in ordinary thinking. It is taken as such without any limitation and without any argument. The clock, the calendar, history, geological periods, astronomical cycles, evoke no doubt in ordinary thought. Unfortunately, this "old-fashioned time" is in need of very serious amendment.

I pointed out in Tertium Organum that in relation to the idea of time, Eastern writings have gone much further than Western philosophy. European theosophists themselves are very fond of quoting words from the Vedanta about the "Eternal Now", etc. But between the "Eternal Now" and the calendar, there are many intermediate stages; and it is just of these intermediate stages that they know nothing.

A man dies, the cycle of his life is closed and, even if the consciousness of his soul is preserved, time disappears. This means that there is no time for the soul; the soul finds itself in eternity. The next day after death, the next year, the next century, do not exist for the soul. In eternity, there can be no direction from "before" to "after"; there cannot be "before" on one side in one direction and "after" on another side, but there must be both "before" and "after" on all sides. If the soul, that is, the completed life, is attracted anywhere, it can be attracted either into "before" or into "after" along any "great line" at the point of intersection of which it is found. It follows that if reincarnation is possible, it is possible in any direction of eternity.

Let us imagine that for the completed cycle of the life of a man, the "great line" is the line of the existence of the Earth. Then the path of the soul can lie along this line in both directions, not necessarily in one direction only. The errors in our reckoning of time lie in the fact that when we think of time, we straighten out several curves simultaneously: the life of man, the lives of the big organisms of human societies, the life of the whole of humanity, the life of the Earth, the life of the Sun. We take all these lives as parallel lines and, moreover, as commensurable lines capable of being expressed in the same units of measure. In reality, this is impossible; for these curves are neither parallel nor commensurable. We ascribe to them this parallel quality only because of the linear quality of our thinking and the linear quality of our conception of time.

Difficult though it is for us to get rid of linear thinking and linear conceptions, we nevertheless know enough to be able to understand that one time, measured by hours, days, geological periods, and light years, does not exist. It is therefore possible to speak of time for a completed circle only when this circle again catches on to some large circle; but when it will catch on and, whether to the right or the left, "before" or "after", it is in no way predetermined. We overlook the fact that the predetermination presumed by us is based exclusively on the imaginary analogy of the division of a small circle with the divisions of large circles. This analogy is built on the supposition that a large circle must be divided into "before" and "after" at the point at which a small circle (a "life" or a "soul") happens to be on it — like the division of the small circle into "before" and "after" during the life of man, with the condition that the direction from "before" to "after" must be the same in both cases.

It is perfectly clear that all these suppositions and analogies have no basis and that the direction of the possible motion of the small circle in eternity is not in any way predetermined.

It is possible to admit that this "small circle", that is, the "soul" or the "life", is subject to some kinds of magnetic influences which may attract it to one or another point of one or another large circle, but these influences must come from very varied directions.

One may not agree with all the deductions from the above arguments; but with a certain understanding of the matter it is no longer possible to dispute the impossibility of a non-relative time, that is, a general time taken for everything that exists. In every given case, time is only the period of existence of the subject in question. This alone makes it impossible to regard time after death in the same way as time before death.

What does the change we call "death" actually mean? As was shown earlier, this change means that the time of the given individual ends. Death means that there is no more time. When the Angel of the Apocalypse says that "there should be time no longer", he speaks of the death of humanity.

All this makes quite clear the impossibility of an elementary treatment of the question without an analysis of the problem of time. Reincarnation, if it exists at all, is a much more complicated phenomenon, and to understand it one must have a certain knowledge of the laws of time and eternity.

The laws of time and eternity are illogical laws. They cannot be studied with the four rules of arithmetic. In order to understand them, one must be able to think irrationally and without "facts". There is nothing more deceptive than facts when we cannot have all the facts referring to the matter under discussion and are forced to deal only with accessible facts which, instead of helping us, only distort our vision. How can we know that we have a sufficient quantity of facts for judgment in one direction or another if we have no general plan of things and know no general system? Our scientific systems based on facts are as deficient as the facts themselves. In order to come to the laws of time and eternity, we must start with the understanding of the state in which there is no time and no eternity opposed to one another.

Table of Contents

The "Eternal Now" is the state of Brahma, the state in which "everything is everywhere and always", that is, in which every point of space touches every point of time, and which in symbolism is expressed by two intersecting triangles, a six-pointed star.

In this combination, time is three-dimensional, just as space is three-dimensional.

But there is a great difference between the three-dimensional time of Brahma and the ordinary human one-dimensional time — the line of time which comes from an unknown past and disappears into an unknown future. This difference is not merely subjective. Man is in fact a one-dimensional being in relation to time. This means that in leaving the line of time, i.e., in dying, man does not immediately find himself in the state of Brahma or in the "Eternal Now". There must be many intermediate states, and it is these intermediate states that we must now examine.

If we take as a point of departure the proposition that the aim of the evolution of the human soul must be the attainment of the state of Brahma, of the "Eternal Now", then the direction of our thought becomes clear.

From this point of view man, that is, his soul (taking this word without any sophistry, simply in the sense of man's inner being, of his inner existence, of which his body is the temporary receptacle), is a spark of Brahma, a seed of Brahma, which by evolving and developing can attain to the state of Brahma in the same way as the seed of an oak by sprouting and growing becomes an oak and, in its turn, produces similar seeds.

But the analogy with an oak, a butterfly, or any other living being, while demonstrating correctly certain aspects of the evolution of man, obscures other sides of this evolution. The analogy of an oak, etc., does not contain the "Eternal Now". If we want to introduce the "Eternal Now", we must introduce another analogy.

Let us compare Brahma to a river. He is the source of the river, he is the river itself, and he is also the sea into which the river flows. A drop of water in the river, having emerged from Brahma, wishes to return to Brahma. Brahma is All. He is the river, the sea, and the source. But to return to Brahma means to return to the source, because otherwise, if the drop is satisfied with a philosophical contemplation of its own possibilities, it may say to itself that it is already in Brahma because Brahma is All, and once the drop is in the river, it is in Brahma, and once it flows with the river towards the sea which is also Brahma, it approaches still nearer to the merging with Brahma. But actually, in this way, it may be further and further removed from the source; and Brahma is the source.

In order to unite with Brahma, the drop must return to the source. How can the drop return to the source? Only by moving against the current of the river, against the current of time. "The river" flows in the direction of time. A return to the source must be a movement against time, a movement not into the future, but into the past.

"Life" as we know it, all the external and internal life of everything, flows in one direction, from the past to the future. All the examples of "evolution" we are able to find also proceed from the past towards the future. Of course, it only appears to us to be so, and it appears so because we build our straight line of time from a multitude of curves such as the lives of men, the lives of peoples, races, etc. For this purpose, we artificially straighten out these curves. But they remain straight only so long as we keep them in our mind, that is, so long as we deliberately see them as straight lines. As soon as we let our attention relax, as soon as we leave some of these lines and pass to others, or to the imaginary whole, they immediately become curves again and thus destroy the entire picture of the whole. At the same time, so long as we see only one line of time, only one current, and cannot see the parallel and perpendicular currents, we cannot see the reverse currents which must undoubtedly exist because, after all, time taken as a surface is not a flat surface but must necessarily be a kind of spherical surface on which the beginning of a line is also its end, and the end is its beginning.

Let us take again the idea of return to Brahma. Brahma has created the world, or the world has emerged and is emerging from Brahma. Three ways must lead to Brahma: movement forward into the future, movement backward into the past, and movement on one spot in the present.

What is movement into the future?

It is the process of life, the process of reproducing oneself in others, the process of the growth and development of human groups and of the whole of humanity. Whether there is evolution in this process is a question open to dispute. What is clear is the picture of the formation, of the existence and dying, of the big jelly-like organisms which fight each other and devour each other — that is, of human societies, peoples, and races.

What is movement on one spot, in the present?

It is movement along the circle of eternal recurrence, the repetition of life, and the inner growth of the soul which becomes possible owing to that repetition.

What is movement backward into the past?

It is the path of reincarnation which, if it is possible and exists, probably exists only in the form of reincarnation into the past.

This is precisely the hidden "esoteric" side of the idea of reincarnation, which is so completely forgotten that even allusions to it are difficult to find. But such allusions exist. I will point only to some strange allusions in the Old Testament.

King David says, in dying: I go the way of all the earth. (1 Kings 2:2).

Joshua says: And, behold, this day I am going the way of all the earth. (Joshua 23:14).

What is the meaning of these words? What does "the way of the earth" mean?

The way of the earth is its past. "I go the way of the earth" can mean only one thing, I go into time, I go into the past.

There are also other expressions:

God says this to Moses and Aaron in Mount Hor: Aaron shall be gathered unto his people... (Numbers 20:24).

God says to Moses: ... and die in the mount whither thou goest up, and be gathered unto they people; as Aaron thy brother died in Mount Hor, and was gathered unto his people (Deuteronomy 32:50).

Then Abraham gave up the ghost, and died in a good old age, and was gathered into his people... (Genesis 35:29).

Then Isaac gave up the ghost, and died, and was gathered unto his people... (Genesis 35:29).

I (Jacob) am to be gathered unto my people... (Genesis 49:29).

And (Jacob) yielded up the ghost, and was gathered unto his people (Genesis 49:33).

Behold, therefore, I will gather thee (Josiah) unto thy fathers, and thou shalt be gathered into thy grave in peace; and thine eyes shall not see all the evil which I will bring upon this place. (2 Kings 21:20). [God says this to Josiah through the prophetess. — PDO]

The words "to be gathered unto his people" have exactly the same meaning as the words "to go the way of all the earth". The last passage, which begins with the words "I will gather thee unto thy fathers", even points out the benefit resulting from it, that is, escape from the evil of the present.

In the usual interpretation, these words are regarded either as indicating a life after death in which a man joins his ancestors who have passed there before him or, in a more materialistic sense, as burial in family tombs.

But the first, that is the interpretation explaining these words by existence after death, does not bear criticism, for it is well known that Judaism contained no idea of existence after death. Had there been such an idea, it would necessarily have been expounded and interpreted in the Bible. Neither does the second explanation (that is, burial in family tombs), answer all the indications mentioned, for the same words also refer to Aaron and Moses, who died and were buried in the desert.

It is particularly important to note that the expressions "to go the way of all the earth", "to be gathered unto one's fathers", or "to be gathered unto one's people" never refer to ordinary men or women; these expressions are used only in relation to very few: patriarchs, prophets, and leaders of the people. This points to the hidden meaning and hidden aim of "reincarnation in the past".

Table of Contents

In the great stream of life which flows from its source, there must necessarily be contrary and transverse currents — just as in a tree there is a flow of sap from roots to leaves and a flow of sap from leaves to roots. In the great stream of life, the evolutionary movement must be a movement contrary to the general process of growth, a movement against the current, a movement towards the beginning of Time — which is the beginning of All.

At the first glance, this is a very strange theory. The idea of a backward movement in time is unknown and incomprehensible to us.

Actually, however, this idea alone explains the possibility of "evolution" in the true and large meaning of the word.

Evolution, i.e., improvement, must come from the past. It is not enough to evolve in the future, even if this were possible. We cannot leave the sins of our past behind us. We must not forget that nothing disappears. Everything is eternal. Everything that has been is still in existence. The whole history of humanity is "the history of crime", and the material for this history continually grows. We cannot go far forward with such a past as ours. The past still exists, and it gives and will give its results, creating new and ever new crimes. Evil begets evil. In order to destroy the evil-consequence, it is necessary to destroy the evil-cause. If the cause of the evil lies in the past, it is useless to look for it in the present. Man must go back, seek for and destroy the causes of evil, however far back they may lie. It is only in this idea that a hint of the possibility of a general evolution can be found. It is only in this idea that the possibility of changing the karma of humanity lies, because changing the karma means changing the past.

The theosophical theory is that every man receives as much evil as he produces. This is "karma" according to theosophical conception. But in this way, evil cannot diminish and must necessarily grow. Humanity has no right to dream of a beautiful and bright future while it drags behind it such a trail of evil and crime which is automatically renewed. The idea of what humanity should do with this load of evil and crime it has accumulated occupied the minds of many thinkers. Dostoevsky could never get free of the horror of the past sufferings of people long dead and vanished. Fundamentally, he was undoubtedly right. Evil, once created, remains and breeds new evil.

Of the better known great teachers of humanity and founders of religions, only Christ and the Buddha never advocated any form of struggle with evil by means of violence — that is, by means of new evil. What has been the outcome of the preaching of love and mercy, we know very well.

If evil can be uprooted and its consequences destroyed, it is only if it is arrested at the moment of its inception — and arrested not by means of another evil.

All the absurdity of the struggle for a better organisation of life on Earth is due to the fact that people attempt to fight the results, overlooking the causes of evil and creating new causes of a new evil. As yet, the precept "do not oppose evil by evil" cannot produce any results because, on their level of development, people can only either be indifferent to evil or struggle with evil (or with what they call evil) by means of violence — that is, by means of another evil. This struggle is always s struggle against results. People can never reach the causes of evil. It is easy to understand why this is so. The causes of evil are not in the present. They are in the past.

There would be no possibility of thinking of the evolution of humanity if the possibility did not exist for individually evolving men to go into the past and struggle against the causes of present evil which lie there. This explains where these people disappear who have remembered their past lives.

From the ordinary point of view, this sounds like an absurdity. But the idea of reincarnation contains this absurdity — or this possibility.

In order to admit the possibility of reincarnation into the past, it becomes necessary to presume plurality of existence, or again co-existence, that is to say, it becomes necessary to suppose that the life of man, while repeating according to the law of eternal recurrence at one "place in time", if it can be put thus, simultaneously occurs at another "place in time". Moreover, it can be said with almost complete certainty that a man, even approaching the super-human state, will not be conscious of that simultaneity of lives, and will remember one life or the life at one "place in time" as past and feel the other as present.

In the conditions of three-dimensional space and one-dimensional time, plurality of existence is impossible. But under the conditions of six-dimensional space-time it is quite natural because in it, "every point of time touches every point of space" and "every thing is everywhere and always". In the space-time represented by two intersecting triangles, there is nothing strange or impossible in the idea of plurality of existence. Even an approach to these conditions creates for a man the possibility to "go the way of all the earth", to "be gathered to his fathers", which enables him to influence his ancestors or their contemporaries, gradually to change and to make more favourable the conditions of his birth, and gradually to surround himself with people who also "remember".

Let us try to imagine such a situation in a more concrete form. Let us suppose that we know that the whole life of a certain man has been shaped in a certain way owing to certain things having been done by his grandfather, who dies before his birth. Let us now imagine that the man has the possibility of influencing his grandfather in a certain way at a right moment through some of his contemporaries, perhaps simply of opening his eyes to something that he did not know. This may entirely change the conditions of that man's subsequent life, afford him new possibilities, and so on.

Let us suppose again that a certain man who has actual power in his hands, a statesman or politician or reigning sovereign of some past epoch, manifested an interest in the direction of real knowledge. This would have given the possibility of influencing him if there had been a man near him who could do it. Let us suppose that such a man happens to be beside him. This might give unexpected results of a very useful character, opening up new possibilities for a large number of people.